|

A recent stint on call for emergencies brought home the importance of properly handling a common condition. The first patient was a 34-year-old man who had been playing with his daughter and cat. His daughter spooked the cat, which then accidently scratched the man’s left eye. The second was a 47-year-old woman who had a mishap involving a child’s fingernail scratch to her left eye.

They presented within an hour of each other. Both had the classic appearance of a person with a corneal abrasion: they were driven in by a family member, held a washcloth across the injured eye and were in such discomfort with tearing and photophobia that they had difficulty engaging throughout the exam. The main difference I found was that the man had been injured an hour earlier, while the woman had been the previous day.

She sought care at a local emergency room, where she got temporary relief with anesthetic. The remainder of the exam involved the physician using fluorescein dye and a cobalt blue filter to correctly diagnose a corneal abrasion, after which she was prescribed a topical antibiotic and discharged. However, the antibiotic did little to relieve her discomfort once the anesthetic wore off; hence, her presentation to seek treatment and relief after not being able to sleep the night before. Adding insult to injury (literally), she incurred a very substantial bill for her ER visit.

Corneal abrasions are one of the most common ocular emergencies, encountered and treated by optometrists, ophthalmologists, ER physicians, physician assistants and nurse practitioners.1,2 However, it is the eye care professional who is poised to offer the best therapy.

|

|

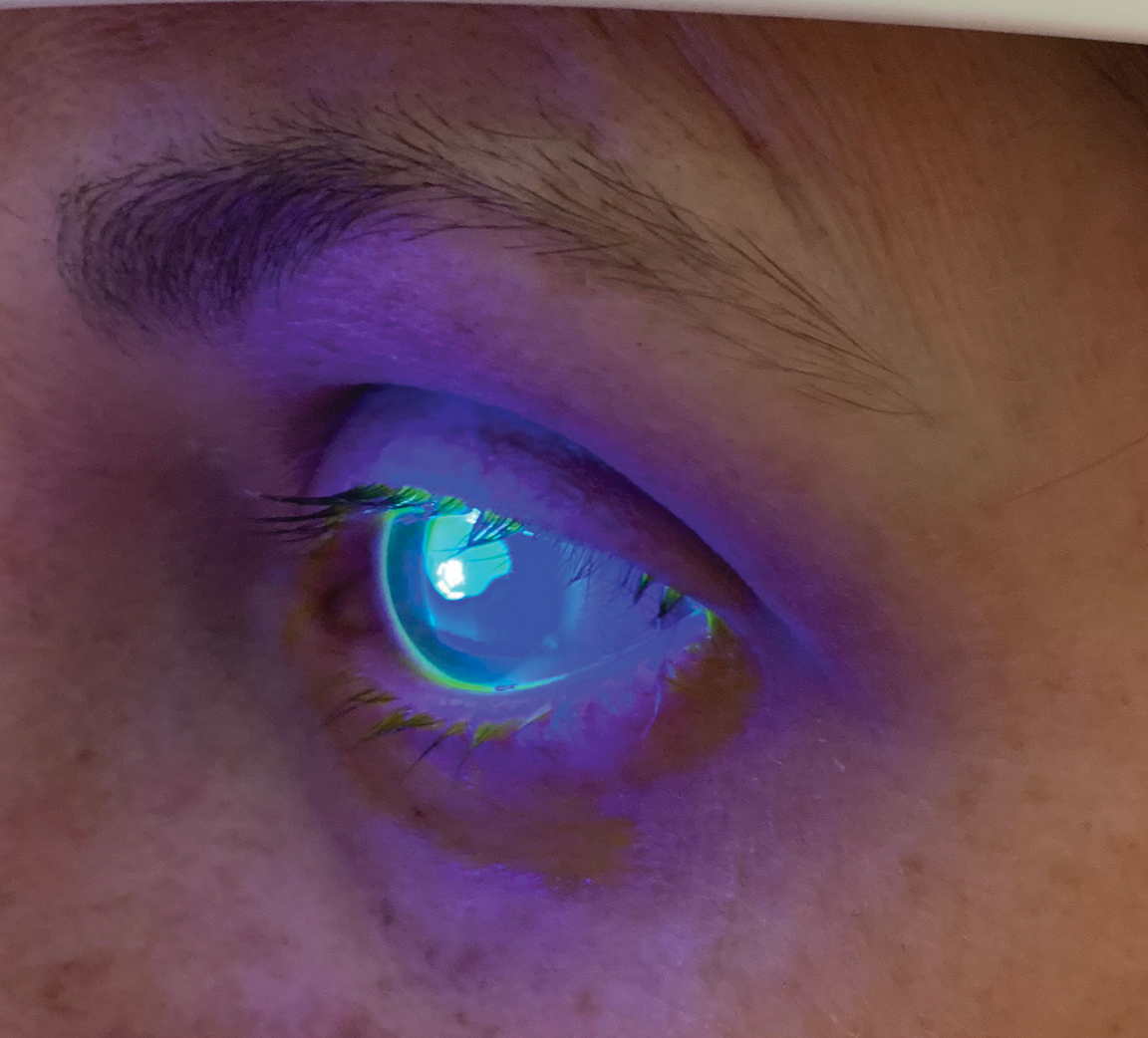

This man had received a corneal abrasion as a result of being scratched by his cat. Click image to enlarge. |

Breaking the Cornea Down

Patients typically present, to varying degrees, with acute pain, photophobia, pain upon blinking and eye movement, lacrimation, foreign body sensation and blurry vision following direct ocular trauma. Biomicroscopy of the injured eye often reveals diffuse corneal edema and epithelial disruption.

In severe cases, folds in Descemet’s membrane may be visible. Cobalt blue light following instillation of sodium fluorescein dye will illuminate the damaged, denuded epithelium with bright green dye accumulation within the abrasion.3 The initial trauma potentially creates a mild anterior chamber reaction (iritis or iridocyclitis).3

The corneal epithelium is comprised of the stratified surface epithelium (whose microvilli increase surface area and permit adherence of the tear film by interacting with its mucus layer), the wing cell layer (containing the corneal nerves) and the mitotically active basement membrane.

Bowman’s membrane prevents penetrating injuries.4 Superficial abrasions do not involve Bowman’s, while deep abrasions penetrate this structure but do not rupture Descemet’s membrane. Abrasions result from numerous causes, including foreign bodies, chemicals, fingernails, hairbrushes and tree branches, to name a few.

The cornea has remarkable healing properties.5 The healthy epithelium adjacent to the abrasion expands and fills in the defect, typically within 24 to 48 hours.6 Lesions that are purely epithelial in nature often heal quickly and completely, without intervention or subsequent scarring. Lesions that extend below Bowman’s membrane leave scars. Stromal opacification after corneal trauma is often due to myofibroblasts and chemokines forming a disorganized extracellular matrix that these cells and their chemokines produce.7

|

|

This woman received her corneal abrasion as a result of being scratched by her child’s fingernail. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment

Management begins with visual acuity and then proceeds from adnexal to fundus examination, if necessary. If blepharospasm precludes an acuity measurement, administer one drop of topical anesthetic and measure the acuity immediately thereafter (pinhole, if necessary). Depending on the nature of the injury, evert the eyelids and examine and flush the fornicies to rule out foreign material. Instill fluorescein dye (without anesthetic) to identify the extent of the corneal defects.

Consider a Seidel test (painting of the wound with fluorescein dye to observe for aqueous leakage) if the injury was high speed with any possibility of full-thickness damage. Clean the abrasion and scrutinize it for foreign matter.

If there are loose or ragged edges of epithelium, these devitalized tissues will impede would healing and should be removed with a cotton-tipped applicator or forceps following instillation of topical anesthesia. Observe the anterior chamber for any evidence of inflammation. A dilated examination may be completed to rule out any posterior effects from the trauma, if indicated.

Prescribe topical antibiotics to prevent infection in cases of corneal abrasion. An inexpensive topical fluoroquinolone or equivalent may be prescribed QID until the cornea has healed. Keep in mind that antibiosis in abrasions is merely prophylactic and will do little to provide healing or comfort. Unfortunately, this is where most non-eye care practitioners end management—with correct diagnosis and prophylaxis but falling short of thorough management. Use topical cycloplegia to put the uvea at rest. This will greatly ameliorate a patient’s pain and photophobia.

Unfortunately, the number of available cycloplegics has been greatly reduced over the years. One drop of 1% atropine or three to five drops of 1% Cyclogyl (cyclopentolate-hydrochloride ophthalmic solution, Alcon) in-office is usually sufficient and typically does not need to be prescribed. For patients who are in a great deal of pain, a topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can be given for acute corneal pain.8 Generic ketorolac or diclofenac can be prescribed BID to QID for a short period of time. Avoid topical anesthetics for these patients due to the potential for misuse, with subsequent neurotrophism. Cold compresses, artificial tears and over-the-counter analgesics such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen can be used to relieve acute pain.

Pressure patching, while no longer commonly used, is still useful for larger abrasions.9 Patching has been commonly replaced by the use of bandage contact lenses, and these have been shown to greatly increase patient comfort, especially when employed with the previously mentioned pharmaceuticals. In cases of corneal abrasion occupying more than 15% of the corneal area, prescribe a thin, low water content, low-powered, high oxygen, extended-wear soft bandage contact lens.10 In cases where there is significant anterior chamber inflammation, a topical steroid or steroid-antibiotic combination agent can be employed; however, the risks of secondary superinfection must be weighed against the benefits.

Topical steroids increase the efficiency of corneal wound healing by suppressing inflammatory enzymes.11 Such use of steroids merits close follow-up. Reevaluate patients every 24 to 48 hours until the abrasion has significantly re-epithelialized. If a bandage lens is employed, the doctor should remove it at the first follow-up using topical anesthesia and thorough irrigation to float the lens off, to not disturb the healing epithelium. It is often prudent to do this at the biomicroscope with forceps rather than digitally to not damage the cornea further. If necessary, a new bandage contact lens can be reapplied if the abrasion is not adequately filled in at the first follow-up.

To Sum Up

Both patients presented here had a similar appearance with corneal abrasions and no evidence of infection.

Following examination, they were cyclopleged in-office with 1% Cyclogel and prescribed a generic fluroquinolone antibiotic QID. A low-powered, soft extended wear soft contact lens was inserted for each patient, and both were reappointed to be seen by the next day. Since the woman had been injured for a longer period and had more discomfort and inflammation, a topical NSAID was added to her regimen QID as well. Upon presentation the following day, both patients felt much better, their bandage lenses were removed and each had nearly 95% resolution of their abrasions.

The woman did inquire about the reasons the emergency room personnel didn’t do as much to make her feel better. It was explained that there are procedures best left to eye care professionals and that, while her treatment was not incorrect and she didn’t get a corneal infection, it didn’t adequately address her pain and discomfort.

Dr. Sowka is an attending optometric physician at Center for Sight in Sarasota, FL, where he focuses on glaucoma management and neuro-ophthalmic disease. He is a consultant and advisory board member for Carl Zeiss Meditec and Bausch Health.1. Kumar NL, Black D, McClellan K. Daytime presentations to a metropolitan ophthalmic emergency department. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33(6):586-92. 2. Wipperman JL, Dorsch JN. Evaluation and management of corneal abrasions. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(2):114-20. 3. Wilson SA, Last A. Management of corneal abrasions. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(1):123-8. 4. Dua HS, Faraj LA, Said DG, et al. Human corneal anatomy redefined: a novel pre-Descemet’s layer (Dua’s layer). Ophthalmology. 2013;120(9):1778-85. 5. Griffith GL, Kasus-Jacobi A, Lerner MR, et al. Corneal wound healing, a newly identified function of CAP37, is mediated by protein kinase C delta (PKCδ). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(8):4886-95. 6. Griffith GL, Russell RA, Kasus-Jacobi A, et al. CAP37 activation of PKC promotes human corneal epithelial cell chemotaxis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(10):6712-23. 7. Torricelli AA, Wilson SE. Cellular and extracellular matrix modulation of corneal stromal opacity. Exp Eye Res. 2014;129:151-60. 8. Thiel B, Sarau A, Ng D. Efficacy of topical analgesics in pain control for corneal abrasions: a systematic review. Cureus. 2017;9(3): e1121. 9. Menghini M, Knecht PB, Kaufmann C, et al. Treatment of traumatic corneal abrasions: a three-arm, prospective, randomized study. Ophthalmic Res. 2013;50(1):13-8. 10. Gilad E, Bahar I, Rotberg B, et al. Therapeutic contact lens as the primary treatment for traumatic corneal erosions. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6(1):28-9. 11. Wang L, Tsang H, Coroneo M. Treatment of recurrent corneal erosion syndrome using the combination of oral doxycycline and topical corticosteroid. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2008;36(1):8-12. |