|

This month’s column title quotes Falstaff from William Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I, and it’s apt for the topic at hand: to adhere to the Hippocratic oath and do no harm, sometimes practitioners must ignore a sacred cow of our training. Optometric education has drilled into us the notion that the goal is clear, single binocular vision. However, in this patient’s case, meeting this goal could have caused more harm than good.

Ultimately, making the patient happy and enabling them to function again are paramount and take precedence over other clinical goals.

Self-described ‘Bobble Head’

Nadine is the 70-year-old mother of a colleague. We first saw her during the holidays in 2015. She has Graves’ disease and had orbital decompression of the left eye in July 2014. In rapid succession, she had three extraocular muscle surgeries, two on the left eye and one on the right, in an attempt to achieve

alignment.

Balance issues. For six months prior to the decompression operation, she wore an opaque patch over the left eye in an attempt to correct the double vision, which resulted in her experiencing balance problems. She reported that if she looked quickly to the left, she experienced an increase in double vision and problems with balance. When watching her approach the examination chair, it was obvious that she moved her head and body, rather than her eyes, to see. She tipped her head regularly and described herself as a ‘bobble head.’ At the end of most days, she had neck and upper back pain and discomfort. In addition, she also had bilateral ptosis and was scheduled for surgery in several weeks.

Ocular motility testing was quite revealing. She was unable to raise her eyes greater than 15 degrees below the horizon. After physically lifting her upper eyelids, we discovered the limitation was in her eye movements. To look at a target and see single in what should be her primary gaze, she had to tip her head back about 10 to 15 degrees. In her current primary gaze—downward about 15 degrees to the midline—she showed a low esophoria of about the same amount at distance and near.

Non-concomitancy. When she moved her eyes 30 degrees to her left, she began to experience vertical double vision. When she moved her eyes 45 degrees to her right, she once again experienced vertical double vision. All testing was performed in downgaze because she had no upgaze.

Her near point of convergence was eight inches; her left eye would go out and she experienced double vision. Visual acuities with her current glasses at distance were 20/40 OD and 20/18 OS. At near, her visual acuities were 20/50 OD and 20/25 OS.

We chose to do a monocular refraction, which yielded the following findings:

-0.25 -1.00 x 20 20/18 OD

+0.50 -0.50 x 10 20/15 OS

|

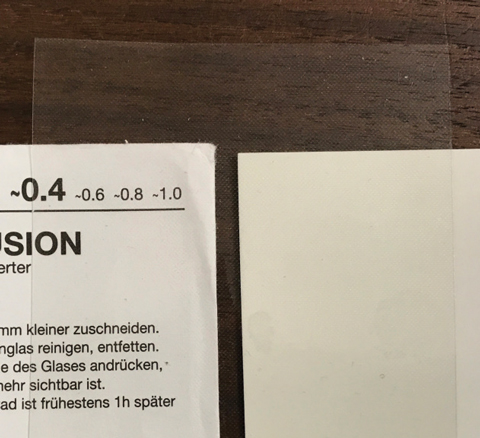

| Here is the Bangerter filter used to treat this patient. |

Back to Mono

We could have tried a prescription that fully corrected the refractive condition, or even explored yoked prism to move objects down to the patient’s field of view, allowing her to keep looking in a downward angle. The yoked prisms might have enabled her to view straight ahead without having to tilt her head back. However, her high level of non-concomitancy was greatly concerning. Had we tried the full correction in a standard multifocal (progressive or trifocal), her non-concomitancy would have made it so that she saw single vision in one and only one position of gaze. To see in other gazes she would have experienced double vision of varying degrees, regardless of whether she moved her eyes to look away from her one location for seeing single.

With her other alternative, had we gone the standard prescriptive route, she would have had to move her head and eyes as a unit, often involving her upper body as well, to maintain single vision. So we went down another path: monovision in glasses.

The patient’s dominant right eye moved more freely over a wider range of movements compared with the left, so we assigned the right and left eyes to see at distance and near, respectively. The final Rx was:

OD -0.25 -0.75 x 20

OS +3.00 -0.50 x 10

When we put this prescription into a trial frame and gave it to the patient, a big smile spread over her face. She looked out at the distance chart and read it easily. To her husband’s surprise, she looked down at the reading material in front of her and started to read out loud. They both remarked that she hadn’t read anything in months and were quite happy with these new results. We suggested trying this prescription for a few weeks and following up to gauge if we needed to make any adjustments.

As often happens, we didn’t see her back until a year later. On September 15, 2016, the patient underwent a second decompression operation, which was scheduled several months prior, but delayed when the patient fell in the waiting area and sustained a blowout fracture of the orbit. So, the second surgery was delayed a few months to give her time to heal.

In general, she reported improvements following surgery. She has decreased pressure and soreness in her face, but the middle branch of the facial nerve seemed to be damaged, most likely from the blowout fracture. She has no feeling in the middle part of her face on the right side and in eight upper teeth on the right side of her mouth. Unfortunately, the monovision glasses broke in the fall and she didn’t have them from July until we saw her again in December. She stated that the glasses dealt with most things, but she still has some diplopia.

|

| The world with and without the 0.4 Bangerter filter. Click image to enlarge. |

Reaffirmation

At this point, the patient says she’s free of double vision early in the day. She notices that it begins at about 5pm each day and gets worse until bedtime. Once diplopia starts, she transforms back into a ‘bobble head.’

We tried, more courageously this time, five-prism diopter yoked base up prism, which raised the area of binocular vision. While it didn’t seem to be significant for her, it relieved some tension in her neck and upper back. Phorias were:

• Six eso at distance with six left infra.

• One to two eso at near, with five left infra to get alignment.

Vergences were done in the phoropter. We needed six diopters of base up prism in the left eye to do the testing at distance and got ranges of X/8/5 base out and X/-2/-3 base in, meaning her clear, single binocular vision ranged from two to eight prism diopters base out with six diopters of vertical prism. This seemed like too much work for such little gain, reaffirming that monovision in glasses might continue to be the best option. Had we put this on her, she would have had to make moment-to-moment choices to either move her eyes and see double or move her head and upper body to attempt to keep the world single. Her binocular system is simply too fragile.

We ordered monovision glasses again; this time, however, we placed a 0.4 Bangerter filter over the upper portion of the left lens, which degraded the image to help eliminate the diplopia at distance. This did the trick—she has been happily using these glasses full time.

There are cases when a practitioner feels they are giving up on fully solving the patient’s visual problems. However, using discretion can help patients achieve greater well-being and become more efficient with their visual processes rather than stretching for clear, single binocular vision. Achieving the best vision possible for your patients while doing no harm is the ultimate end.