|

Q:

I have a post-op cataract patient who, at their one-week visit, had 20/20 vision and a normal dilated fundus exam. At their one-month visit, vision was 20/20-2. Should I get an OCT?A:

“It’s critical to look at the fundus and let your clinical acumen help determine the presence or absence of clinically significant findings, no matter the scenario,” says Jeffry Gerson, OD, of Grin Eye Care in Olathe, KS. “Make sure that it’s you, the clinician, who is doing the diagnostic digging—and not the optical coherence tomography (OCT).” The machine is only as good as the optometrist’s expertise to determine the need for referral based on the findings of their dilated exam, Dr. Gerson explains.

|

| Not every ancillary test can or should be used on every patient. |

The Eyes God Gave You

Not every patient needs extensive testing or OCT imaging—remember, some will never achieve 20/20 vision. “The primary modality for finding pathology has long been, and should continue to be, the good, old-fashioned clinical exam,” says Dr. Gerson. Not every ancillary test can or should be used on every patient, he says.

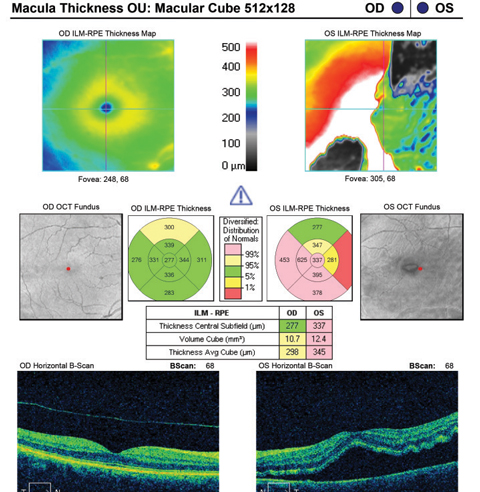

For instance, later in the post-op course, CME is one of the more common complications following cataract surgery.1 However, this doesn’t mean that OCT takes the place of your fundus examination, says Dr. Gerson. “Clinicians should be able to observe conditions—in this particular example, CME—with a condensing lens at the slit lamp,” he explains. While OCT can serve as a confirmatory test, it’s not likely needed to make a diagnosis.

“In general, if somebody corrects to only 20/25, then clinical examination should rule out such significant pathologies as dry eye and cataracts. Most macular pathology, as well, can be seen on careful clinical examination,” says Dr. Gerson. Of course, some subtle changes will be seen with OCT that are not evident on exam, but this should be the exception and not the rule when vision is decreased, he explains. “Visually significant pathologies, whether they are macular edema, macular degeneration or pigmentary changes, should be evident via the clinical examination.”

What’s the Harm?

Given the utility of OCT in various situations, it’s tempting to say there’s no harm in doing OCT in any and all contexts; however, clinicians must rely on their clinical skills and remember the value of dilation to reveal the presence or absence of conditions warranting referral.

“There is the possibility of over-referral, in a post-op or any other patient that comes back with an ‘abnormal OCT’,” says Dr. Gerson. It’s imperative clinicians use the OCT in conjunction with the history and clinical exam before sending a patient out to a retina or glaucoma specialist, or back to the cataract surgeon, he explains.

“Sending a patient for a second opinion and giving the patient the impression that a significant, possibly vision-threatening issue exists can put them on an emotional roller coaster,” says Dr. Gerson. Worry, despair and anxiety due to a potential vision problem lead to anger and frustration when the patient finds out that their anxiety was ultimately unfounded, explains Dr. Gerson.

So, before ordering an OCT, look at the fundus and put the findings together. OCT is a great ancillary tool, but it’s dangerous to stop looking directly at the fundus and let the OCT ‘do the thinking.’ “Ultimately, the machine is the not clinician—you are,” says Dr. Gerson. “Using the eyes God gave you will prove the most fruitful when discerning the need to refer.”

| 1. Henderson B, Kim J, Ament C, et al. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema-Risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:1550-8. |