|

A 51-year-old black woman presented for ocular examination complaining of blurry vision in both eyes. Her ocular history was unremarkable, but her systemic history was complex. In addition to hypertension, she had cardiovascular disease, thyroid disease, asthma, herpes zoster and multiple strokes, the most recent of which was one year ago. Currently under the care of an internist and a cardiologist, her medications included metoprolol, furosemide, spironolactone, digoxin, levothyroxine, baby aspirin, Xarelto (rivaroxaban, Janssen) and Protonix (pantozaprole, Pfizer).

|

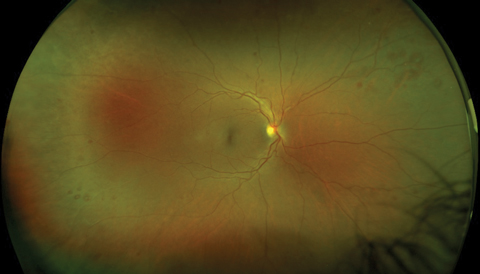

| Our patient’s right fundus demonstrates scattered midperipheral, white-centered retinal hemorrhages. Similar findings also appeared in the left fundus. Click image to enlarge. |

Evaluation

Upon examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OD and 20/25+ OS. Motilities and visual fields by confrontation were normal in both eyes, and pupils were reactive without afferent defect. Intraocular pressures (IOP) were 20mm Hg OD, 23mm Hg OS. Examination of the anterior segment revealed mild lenticular changes, but was otherwise unremarkable. Fundus evaluation disclosed a pink, healthy optic disc and an intact fovea in each eye. The retinal vasculature was mildly dilated and tortuous in both eyes, with minimal crossing changes. Of note, there were multiple, deep, round retinal hemorrhages, many with distinctively white centers, primarily located in the midperiphery of both eyes. There was no evidence of macular edema, retinal exudate, cotton-wool spots or neovascular changes in either eye.

White-centered retinal hemorrhages— commonly known as “Roth spots”—can be an alarming finding for any eye care practitioner. These lesions are believed to represent a rupture of retinal capillaries, with extrusion of blood and subsequent platelet adhesion to the damaged endothelium.1,2 The release of platelets initiates a coagulation cascade, which leads to the formation of a platelet-fibrin thrombus; this accounts for the white center of each hemorrhagic lesion.1,2

For years, Roth spots were believed to be pathognomonic for subacute bacterial endocarditis, a potentially life-threatening infection of the cardiac endothelium.1-6 Today, however, we recognize that these lesions can be encountered in numerous other conditions, including hypertensive and diabetic retinopathy, as well as connective tissue disorders such as systemic lupus, ankylosing spondylitis and Behçet’s disease.1,2,4,7,8 Additionally, other infectious diseases may present with this retinal finding, including toxoplasmosis, leishmaniasis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).9-11 Numerous blood dyscrasias have also been associated with Roth spots, and this finding can portend such insidious conditions as anemia, thrombocytopenia and even several types of leukemia.2,5,12-16 Rarely, Roth spots have been noted in association with anoxia and carbon monoxide poisoning, severe head trauma (especially in children and infants) and intracranial hemorrhage.1,12,16-18 The central stimulating factor seems to be increased capillary fragility, intravascular coagulopathy or both.4

Testing Protocol

When funduscopic exam reveals Roth spots, particularly in cases where the medical history is unknown or reportedly unremarkable, a systemic evaluation for disease is crucial. Initial testing should include an assessment for hypertension, a fasting plasma glucose test, serum lipid profile, complete blood count with differential and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate. These tests will help identify the vast majority of conditions mentioned, including diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, blood dyscrasias and potential collagen-vascular disorders. Additional tests can include blood cultures, cardiac evaluation and specific serology for infectious disorders or autoimmune disease.

If the patient is not in acute distress, and if they have an established primary care provider (PCP), we coordinate care with that physician rather than ordering testing directly. In most cases, the PCP has detailed knowledge of the patient’s condition and medications that may provide additional insight, thereby reducing the number of diagnostic tests required. Also, the PCP will ultimately be the one to initiate treatment for any underlying disease, and having the laboratory results sent directly to that individual facilitates more efficient care of the patient.

Comanagement

In our case, we elected to communicate with the PCP and inform him of the noted changes. We reviewed the potential etiologies associated with white-centered hemorrhages and suggested the diagnostic evaluation. We also asked about rivaroxaban—which has been associated with retinal hemorrhages in several case reports—and whether that or any of her other medications might be potentiating the anticoagulation effect.19 Neither we nor the PCP were aware of any reports of Roth spots associated with the use of rivaroxaban or any other anticoagulants. Moreover, the only potential drug interaction in this case was between rivaroxaban and aspirin. While numerous drugs can potentiate warfarin, the newer generation anticoagulants are specific inhibitors of clotting factors and are not linked to vitamin K use.19 For this reason, the list of medications and other supplements that should be avoided is far smaller for rivaroxaban than for warfarin.

At press time, we were still awaiting results of this patient’s diagnostic laboratory evaluation.

1. Ling R, James B. White-centred retinal haemorrhages (Roth spots). Postgrad Med J. 1998 Oct;74(876):581-2. |