A 19-year-old white male, a recruit at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in San Diego, presented to update his spectacle prescription and receive his boot camp glasses. He complained that his distance vision had decreased with his current glasses, especially at night. He had no other complaints.

The patients last eye examination was six months earlier. His best-corrected visual acuity at that time was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye with a spectacle prescription of 5.25 0.50 x 010 O.D. and 6.00 1.25 x 180 O.S.

His ocular and medical history was unremarkable. He denied any previous ocular trauma, surgery or infection. His family medical history was also unremarkable. He had no known drug allergies and was not taking any medication at the time of his visit.

Diagnostic Data

Upon examination, the patients best-corrected visual acuity at distance and near was 20/20 O.D. and 20/25-3 O.S. with a spectacle prescription of 5.75 0.75 x 012 and 6.25 1.25 x 178, respectively. Pupils were round, equal, responsive to light and without relative afferent pupillary defect. Confron-tation fields were restricted in the inferior nasal quadrant of the right eye, and in both the superior and inferior nasal quadrants in the left eye. Extraocular muscle movements were unrestricted and without pain. IOP measured 15mm Hg O.D. and 16mm Hg O.S. All other preliminary findings were within normal limits.

Slit lamp examination revealed clear lids, conjunctiva, cornea and lens in both eyes. Each iris was hazel in color and without defects.

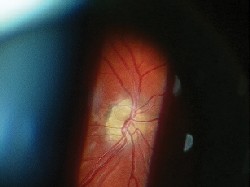

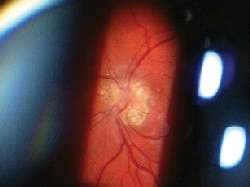

Dilated fundus exam revealed optic nerve head (ONH) elevation with cup-to-disc ratios of less than 0.1/0.1 in both eyes. Both ONH were distinct to 360 degrees, pale in coloration and without hemorrhages. Visible drusen were present in both eyes; they appeared as bright, reflective and lumpy calcifications. The macula and peripheral retina were within normal limits in each eye.

Diagnosis

We preliminarily diagnosed the patient with optic nerve head drusen in both eyes. We also diagnosed him with myopia and astigmatism in both eyes.

Treatment and Follow-Up

We scheduled B-scan ultrasonography, Humphrey 24-2 SITA-Standard Test and digital photography of both eyes, and instructed the patient to return to the clinic after the tests were completed.

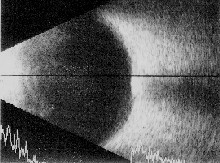

The patient returned to clinic two days later for a follow-up evaluation. B-scan ultrasonography revealed high reflectivity at the ONH in each eye. The Humphrey 24-2 SITA-Standard Test with size III stimulus was reliable for both eyes and showed field defects consistent with the location of the ONH drusen. At this visit, we also administered a color vision test with Ishihara color plates. The results were 11/15 O.D. and 10/15 O.S.

We diagnosed optic nerve head drusen with secondary visual field defects in both eyes.

The Humphrey 24-2 SITA-Standard Test showed field defects consistent with the location of the optic nerve head drusen in both eyes. The results are pitcured above, O.D. and O.S. respectively.

We explained the condition to the patient and informed him that there is no treatment for ONH drusen unless hemorrhagic complications occur. We instructed him to self-monitor his vision weekly in each eye with an Amsler grid, and to seek professional care immediately if he noted any vision defects. We also instructed the patient to continue with routine follow-up care every six to 12 months.

Unfortunately, the patient did not meet the military physical standard and was no longer eligible to serve.

Discussion

ONH drusenalso referred to as congenitally elevated anomalous discs, pseudopapilledema, pseudo-neuritis, buried disc drusen and disc hyaline bodiesoccur in the pre-laminar portion of the optic nerve and are bilateral in 70% of cases.1,2,3 The condition occurs in 1% of the general population, primarily in whites.1,4

The pathogenesis of ONH drusen is not yet fully understood. Current research suggests an abnormally narrow opening of the scleral canal can cause a stasis of axoplasmic flow. This leads to abnormal axonal metabolism and mitochondrial calcifications. These calcifications erupt into the extracellular space and appear as drusen.3

Within the optic nerve, the hyaline bodies are confined to a space anterior to the lamina cribosa, causing compression and compromise of the nerve fibers and vascular supply. This eventually leads to visual field defects and disc hemorrhages.1 Visual field loss occurs in as many as 64% to 87% of patients with ONH drusen, with up to 22% having progressive defects.5

Typically, patients with ONH drusen are asymptomatic. Clinical findings are usually discovered upon a routine eye examination. Decreased visual acuity and visual field defects (arcuate, sectoral and altitudinal scotomas) are present in some cases. An afferent pupillary defect may be present if the condition is both significant and asymmetric.1 On rare occasions, ONH drusen may have associated symptoms such as migraine headaches, seizures and transient visual disturbances.2

Visible ONH drusen appear as glistening, globular or spherical-shaped bodies that protrude forward, causing irregular, indistinct ONH margins. ONH drusen most often manifest on the nasal disc margin, but can be found within any part of the nerve head.1 In younger patients, the disc elevation tends to be more pronounced and the drusen less calcified, making them less visible ophthalmoscopically. ONH drusen can often resemble pseudopapilledema with no physiologic cupping.2 In the early adult years, the disc can become yellowed, and the round refractile drusen may erupt to the surface. The proximity of the drusen to the disc surface and progressive thinning of the nerve fiber layer make the drusen more visible.

When illuminated with a red-free light, these refractile bodies autofluoresce (glow). Ultrasonography is also very helpful in detecting disc drusen, which have high reflectivity even on low gain settings.2

ONH drusen are typically classified as a benign condition, though they can lead to modest visual compromise.1 However, other conditions can present similarly to ONH drusen, so differential diagnosis is critical. Other possible etiologies include papillitis, malignant hypertensive retinopathy, central retinal vein occlusion, ischemic optic neuropathy, optic disc vasculitis, infiltration of the optic disc, Lebers optic neuropathy, orbital optic nerve tumors, diabetic papillitis and Graves ophthalmopathy.3,4,6

B-scan ultrasonography on this patient revealed high reflectivity at the site of the optic nerve head drusen in each eye, seen here.

Management of ONH drusen includes prompt and proper diagnosis.

Ultrasonography is probably the single most important ancillary test to perform in adults with ONH drusen. Ultrasonagraphy may not be as helpful in children because the drusen are not calcified.4 A careful evaluation of the optic nerve function is critical and should include Snellen acuity, contrast sensitivity, color vision testing and visual fields. Photodocumentation should be obtained for future comparison of progression.

There is no treatment or preventative care for patients with ONH drusen, unless hemorrhagic complications occur. Hemorrhages may be retrovitreal, preretinal, intraretinal or subretinal. Treatment options include natural resorption, photocoagulation, vitrectomy and scleral buckling, depending on the location and severity of the hemorrhage.

Educate patients on the importance of annual eye exams to monitor for progression. Patients must also self-monitor their vision periodically and return to the clinic as soon as possible if they note any visual disturbances. Routine ONH drusen cases should be seen every six to 12 months.1

Dr. Dang is a lieutenant in the U.S. navy and serves as staff optometrist for the Naval Medical Center in San Diego.

1. Sowka JW, Gurwood AS, Kabat AG. OpticNerve Head Drusen. Handbook of Ocular Disease Management. Rev Optom Online, www.revoptom.com/handbook/SECT50a.htm.

2. Nishimoto J. Anomalies of Optic Disc Contour and Position. In: Bezan D, LaRussa F, Nishimoto J, et al. Differential Diagnosis in Primary Care. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999:388-9.

3. Haynes RJ, Manivannan A, Walker S, et al. Imaging of optic nerve head drusen with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Br J Ophthalmol 1997 Aug;81(8):654-7.

4. Chang A, Flaherty M. Disc Drusen: A headache for child and clinician. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1996 Nov;24(4):381-4.

5. Mustonen E. Pseudopapilledema with and without verified optic disc drusen. A clinical analysis II: visual fields. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983 Dec;61(6):1057-66.

6. Roh S, Noecker RJ, Schuman JS, et al. Effect of optic nerve head drusen on nerve fiber layer thickness. Ophthalmology 1998 May;105(5):878-85.