|

A 78-year-old Caucasian female came in for a routine comprehensive eye examination. She was only correctable to 20/100 OD and 20/60 OS. The main culprit, as had been noted the year prior, was cataracts. She was scheduled for cataract surgery last year but had cancelled since she felt that she didn’t need it. Indeed, she still felt fine and had no problems with her vision despite the reduced acuity. Her refraction was essentially unchanged and didn’t improve her acuity.

Notably, she was a moderate hyperope in the +2.75D range in each eye with mild astigmatism. Her intraocular pressures (IOP) were 17mm Hg OD and 18mm Hg OS, similar to last year’s findings. It was apparent that she had a very shallow anterior chamber with narrow angles. A glaucoma surgeon strongly recommended prophylactic laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI). Like the cataract surgery, she cancelled that procedure as well.

Assessing and managing patients with chronic angle closure and those at risk of angle closure is challenging. Prophylactic LPI aims to prevent progression to acute or chronic angle closure. But it has always been difficult to identify those patients who would most benefit from the procedure, with most clinicians following their own personal experiences in recommending and performing LPI.

|

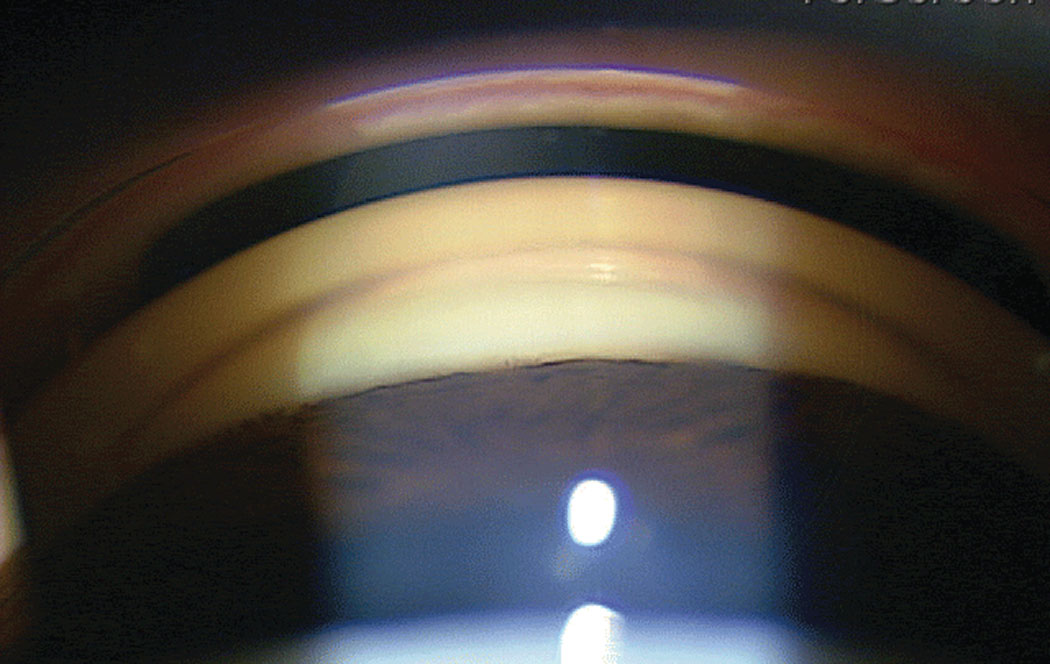

| This semi-narrow angle patient is a candidate for LPI. Photo: Ian McWherter, OD, and Richard Mangan, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The Angle Closure Spectrum

Historically, the term narrow angle glaucoma has been used to connote eyes either at risk of impending angle closure or those actually experiencing it. Though this term is still used today, it is more appropriate to speak in current terms of angle closure and assign eyes to one of four categories.

The first category is the primary angle closure suspect. Here, the pigmented trabecular meshwork is blocked by the iris for 180º. There is no peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS), the optic disc is normal and IOP is not elevated. These are the “at-risk” patients who are commonly encountered in clinical practice and often additionally have a low-to-moderate degree of hyperopia leading to crowding of the anterior chamber. It is not clear if LPI or observation is better for these patients.

The second category is primary angle closure where the pigmented trabecular meshwork is likewise blocked by the iris for 180º. In contrast to the suspect, these eyes will have either PAS, elevated IOP or both. But there still is no disc damage or visual field loss. In these eyes, LPI is recommended.

The third category is primary angle-closure glaucoma that has all the features mentioned previously for primary angle closure but, additionally, has progressed to involve glaucomatous neuropathy and often visual field loss as well. In this situation, LPI is also recommended.

The final category is the well-known primary angle-closure attack, with near complete apposition of the iris to the pigmented trabecular meshwork. Its classic signs and symptoms include redness, vision loss, nausea, emesis, halos, corneal edema, elevated IOP, inflammation, and a mid-dilated fixed pupil.

PCACG Management

Primary chronic angle-closure glaucoma (PCACG) is the predominate form of the ocular disease and is more commonly encountered than acute attack. Anatomical features act in concert to cause shallowing of the anterior chamber. As a patient ages, thickening of the crystalline lens leads to a relative pupil block that exacerbates and partially contributes to the condition.

Since the closure is slow, there is an absence of symptoms that would typify an acute angle closure. There is more of a multi-mechanism, with some degree of pupil block as well as an anteriorly located lens and ciliary body that causes shallowing of the anterior chamber and overall congestion of the angle, leading to creeping synechial closure.1,2

PCACG is typically treated with LPI, though primary pupil block is not the major mechanism. While LPI can alter the anatomical status of the angle, a significant number of these patients will manifest residual angle closure after LPI from PAS.3 Additionally, there will often be elevated IOP despite a laser-induced open anterior chamber angle due to damage to the trabecular meshwork from appositional and synechial closure.4

Medical therapy that has been successful in ameliorating the IOP in eyes with PCACG includes beta blockers, miotics, alpha-2 adrenergic agonists and prostaglandins.5,6 Prostaglandin analogs seem to work especially well in eyes with PCACG that need IOP reduction both before and after LPI.7 These medications are thought to lower IOP by increasing matrix metalloproteinase activity and subsequently reducing the amount of extracellular matrix material surrounding the ciliary muscle fiber bundles.8

New Players in the Game

Preventing angle closure through LPI is commonly done in patients deemed anatomically at risk. LPI increases angle width in all stages of primary angle closure and has a good safety profile.9 As mentioned, it is often difficult to determine which patients at risk of angle closure would most benefit from prophylactic LPI to prevent future disease. Recent study results have shed light on this issue.

One study noted that the rate of developing any angle closure endpoint was much lower than expected in primary angle closure suspect eyes at less than 1% per year.10 Eyes that underwent LPI did have a 47% reduction in the risk of developing primary angle- closure or an acute attack.10 LPI was safe with no long--term adverse events.10 However, the study argued that prophylactic LPI is only of modest benefit over time, given the very low progression rate observed.10

While LPI is largely safe and easily performed, there may be less of a need for it based on the low incidence of conversion from primary angle closure suspect to pathological angle closure. At the very least, this study indicates that prophylactic LPI is not urgent in patients who are only anatomically at risk.

While LPI and stepped medical therapy (if needed) have been the traditional approach to managing patients with PCACG, results from the Effectiveness in Angle-closure Glaucoma of Lens Extraction (EAGLE) Study suggested an alternate and perhaps better option: phaco. Patients who underwent phacoemulsification lens extraction needed fewer IOP-controlling medications than those undergoing traditional therapy.11 Only one patient needed trabeculectomy after phacoemulsification, compared with 24 patients in the LPI group.11 Lens extraction was also seen to be the more cost-effective option.12

Researchers have shown that lens removal is a more effective treatment for an acute primary angle-closure attack than LPI. Compared with eyes that underwent LPI, the phacoemulsification eyes experienced fewer IOP elevations, required fewer medications and had deeper angles following lens removal.13

Does this compelling new information change our management? Prophylactic LPI provides a significant reduction in risk of future angle closure complications, but very few patients progressed on to these complications without LPI. Since prophylactic LPI has been done for so long and has relatively few risks, most practitioners will still tend to do the procedure in eyes deemed “at risk” of closure. Removing a cataract in an eye with PCACG is easily justifiable, but removing a clear lens is harder to justify to patients and insurers.

Likely, LPI and medical therapy will remain popular. Removing the lens in acute closure situations may have some significant benefits, but LPI is easier to perform urgently and has a documented history of success.

For the patient presented here, dilation was deferred due to the potential of acute closure. She was educated about the condition and referred again for LPI.

| 1. Wang T, Liu L, Li Z, Zhang S. Studies of mechanism of primary angle-closure glaucoma using ultrasound biomicroscope. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 1998;34(5):365-8. 2. Marchini G, Chemello F, Berzaghi D, Zampieri A. New findings in the diagnosis and treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma. Prog Brain Res. 2015;221:191-212. 3. Sihota R, Lakshmaiah NC, Walia KB, et al. The trabecular meshwork in acute and chronic angle closure glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2001;49(4):255-9. 4. Su WW, Chen PY, Hsiao CH, Chen HS. Primary phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation for acute primary angle-closure. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20056. 5. Ruangvaravate N, Kitnarong N, Metheetrairut A, et al. Efficacy of brimonidine 0.2% as adjunctive therapy to beta-blockers: a comparative study between POAG and CACG in Asian eyes. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002;85(8):894-900. 6. Aung T, Wong HT, Yip CC, et al. Comparison of the intraocular pressure-lowering effect of latanoprost and timolol in patients with chronic angle closure glaucoma: a preliminary study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(6):1178-83. 7. Chen MJ, Chen YC, Chou CK, et al. Comparison of the effects of latanoprost and bimatoprost on intraocular pressure in chronic angle-closure glaucoma. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23(6):559-66. 8. Lindsey JD, Kashiwagi K, Kashiwagi F, et al. Prostaglandins alter extracellular matrix adjacent to human ciliary muscle cells in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2214-23. 9. Radhakrishnan S, Chen PP, Junk AK, et al. Laser peripheral iridotomy in primary angle closure: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(7):1110-20. 10. He M, Jiang Y, Huang S, et al. Laser peripheral iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure: a single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10181):1609-18. 11. Azuara-Blanco A, Burr JM, Cochran C, et al. Effectiveness of early lens extraction for the treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma (EAGLE): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1389-97. 12. Mehdi Javanbakht M, Azuara-Blanco A, Burr JM, et al. Early lens extraction with intraocular lens implantation for the treatment of primary angle closure glaucoma: an economic evaluation based on data from the EAGLE trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1): e013254. 13. Lam DS, Leung DY, Tham CC, et al. Randomized trial of early phacoemulsification versus peripheral iridotomy to prevent intraocular pressure rise after acute primary angle closure. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1134-40. |