Driving with both visual acuity (VA) and visual field (VF) loss has been a hot topic in the field for decades.1-10 Although the literature routinely acknowledges that driving is a privilege, not a right, loss of driving privileges can have devastating consequences such as increased social isolation, decreased quality of life and depression.11-13 Such high stakes can make the subject of driving tough to bring up during the examination of individuals with visual impairments. However, ODs have a duty to properly assess and counsel patients with congenital or acquired visual impairments who would like to acquire driving privileges or who will become non-drivers because of their vision loss.

Here, we discuss the complexities of the current vision and licensure standards, how they affect patients with vision loss and what ODs can do to properly evaluate and counsel patients who are visually impaired and want to drive.

State Standards

One 1991 study found uniform standards did not exist in the United States for VA, VF or the use of bioptic telescopes—which is still true today.14 Currently, two vision standards exist for driving licensure. Some states enforce a rejection standard: an individual will automatically be rejected for licensure if they do not meet the minimum vision standards for VF or VA. Most commonly, those standards are VA in one or both eyes of 20/40 or better and a binocular field of view of 140 degrees or more. However, significant variances occur; for example, Wisconsin only requires a 40-degree field of view, and a number of states have no VF specification.

The Aging DriverToday, more than five million Americans age 65 and older are afflicted with a form of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease. By 2050, this number is expected to grow to 13.8 million as the baby-boom population ages.1 Data indicates that 50% of persons with Alzheimer’s disease continue to drive up to three years after they have been diagnosed with the disease, and that these individuals also have worse driving performance and are more likely to cause traffic accidents.1-4 Clinicians must be prepared to care for these patients and properly counsel them—and their loved ones—on safe driving.

|

The alternative to the rejection standard is the vision screening standard. Rather than being automatically rejected if they do not meet the minimum standards, individuals may be granted driving privileges after further evaluation of all factors, including a behind-the-wheel test. Iowa, for example, allows for individual review, via a behind-the-wheel test, for individuals with VAs better than 20/200, a VF greater than 20 degrees or both.

In addition to vision standards, two different licensure standards exist for driving, depending on the state. According to some states, as long as the individual’s VA and VFs are adequate enough to allow them licensure, they can continue to drive until that license expires, regardless of how poor their acuity or VFs become during the licensing cycle. Drivers in those states may have a false sense of security, despite changes in their vision, when they have a license that does not expire for several years.

In other states, individuals whose VA or VFs drop below the state’s licensure standards are no longer legal to drive from that time forward, regardless of the licensing cycle. This is the same standard used for commercial licensure, where the driver needs to know they meet the vision standard every time they get behind the wheel of a commercial vehicle. Currently, only a few states, such as Illinois and Pennsylvania, use this standard for driving.5

Above and beyond these vision and licensure standards, states have different protocols for restricted driving privileges, including: daylight-only, no driving when headlights are required, reduced speed, local area driving or a restricted distance from home and no highway driving. States also vary on whether the use of a bioptic telescope is allowed for licensure, as well as what VA requirements must be met, both with the bioptic telescope and the carrier lens.

All of these variations mean an individual could be licensed in some states and not even considered for driving in others.

Clinicians should be familiar with their state’s vision standards for driving to properly educate their patients who are visually impaired. Unfortunately, it can be difficult to know for sure what any given state’s driving laws entail, and you must check each DMV/DOT website or call to clarify.

Case 1A 38-year-old female presented with a history of reduced vision for the past 20 years secondary to Stargardt disease. Her best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/160-2 OD, 20/160-1 OS and 20/125-2 OU. She had small bilateral central scotomas consistent with her central acuity. A discretionary review request was made to the Iowa DOT, and she received unrestricted driving privileges following several behind-the-wheel tests that took place during the day and at night. She has maintained full driving privileges, without incident, for the past 17 years. |

Roadblocks

Given today’s driving environment, the vision screening standards used by state departments of motor vehicles/departments of transportation (DMV/DOT) may not be satisfactory in assessing drivers’ functional vision (Cases 1 and 2).1-10,15

Although VA has been widely used in driving regulations for decades, it is a poor predictor of performance for several reasons:8,9

- The correlation of VA alone to accidents is less than 1%.10

- The minimum standard of 20/40 is based on an American Medical Association recommendation dating back to 1937.16 Research shows individuals with normal sight have a functional VA of less than 20/40 when driving at night at speeds greater than 55mph with high beams on and at speeds greater than 35mph with low beams on.17,18

- The effective lateral field of view when driving with headlights is only 35 to 45 degrees.19

- A driver’s license has no restrictions concerning driving during periods of dense fog, heavy rain or snow—times when even a driver with normal VA will have their vision reduced to this presumed unacceptable level.

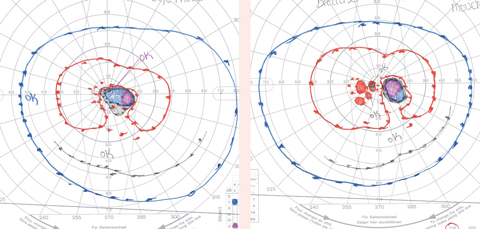

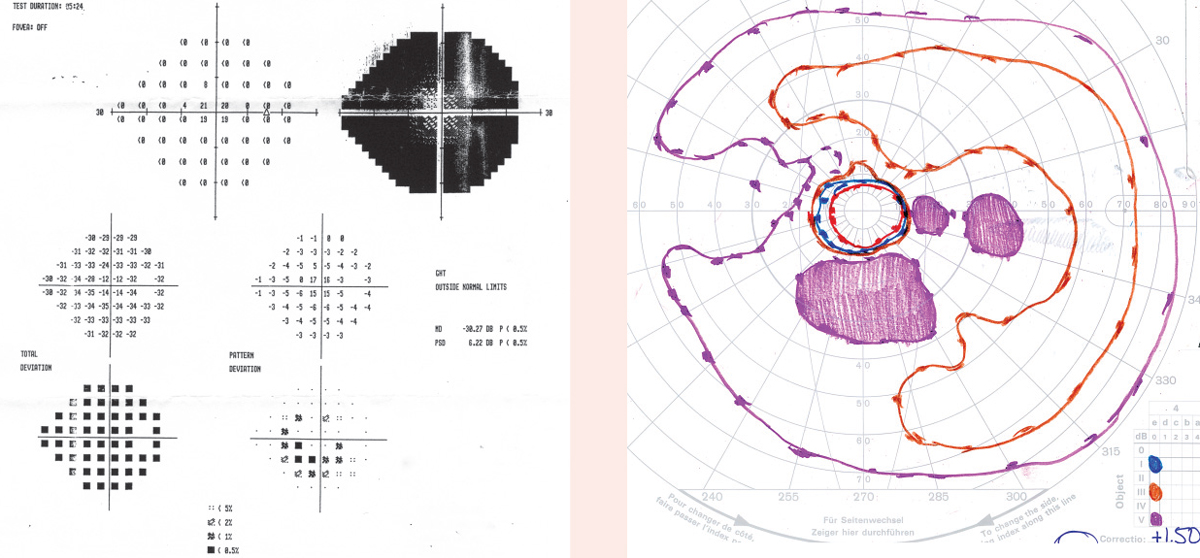

Case 2A 55-year-old male presented for an evaluation stating that he was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa three months prior. He noted that he has been “losing things” when he puts them down for the past 15 to 20 years. He stated that based on recent threshold-related central VF testing, he was told to stop driving, get a cane or a guide dog and learn Braille. His BCVA was 20/25 OD/OS. He stated he has driven cautiously for many years without incident. Furthermore, he lives in a state that has no VF requirements. When non-threshold related, full-field testing was performed, we found he had relatively full fields to the larger isopters tested (III4e and V4e), with scattered paracentral scotomas. Based on his full-field testing and VA, he was advised that he did not need to stop driving, nor did he need a guide dog or Braille literacy.

Click images to enlarge. | ||||

Vision Testing for Driving

High-contrast VA testing under photopic conditions continues to be the standard for licensure. However, additional visual function tests not currently used in the United States for driving licensure may be helpful when evaluating functional abilities behind the wheel:8-10

Full-field, non-threshold visual field testing. Testing that includes at least the I4e and a V4e isopter is valuable information, even in states that do not specify VF requirements. Alternately, the SSA Kinetic testing strategy on the Humphrey field analyzer (Zeiss) could be used with the standard testing protocol as well as a V4e equivalent isopter.

Adapted and Semi-Autonomous CarsIn 2016, a total of 37,461 deaths and two million injuries were from automobile accidents, a 5.6% increase from 2015.1 With these staggering numbers, it’s no wonder so much attention has been focused on semi-autonomous safety systems and their potential to reduce accident rates. But this technology could also have a significant impact on our low vision patients. It may one day allow individuals with visual acuity and visual field loss the ability to continue driving, just as those with physical handicaps, including loss of limbs, currently have the ability to operate an adapted motor vehicle and be licensed to drive. 1. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. USDOT releases 2016 fatal traffic crash data. October 6, 2017. www.nhtsa.gov/press-releases/usdot-releases-2016-fatal-traffic-crash-data. Accessed January 31, 2018. |

Contrast sensitivity. This is an important test for assessing an individual’s fitness to drive because research shows it is predictive of driving outcomes for individuals older than 65 with normal vision.8

A common cause of contrast sensitivity loss is cataracts, and drivers with cataracts are 2.5 times more likely to have an at-fault accident than those without cataracts.8,20-24 Additionally, individuals with cataracts are four times more likely to report difficulties with driving compared with individuals without cataracts.8,20-23 Some individuals with binocular cataracts continue to experience driving difficulties, even after monocular cataract surgery.23 Research shows improved contrast sensitivity after cataract surgery is more valuable than improved visual acuity when assessing driving difficulties due to vision.10 Finally, one study found that contrast sensitivity of less than 1.25 log units was the only independent predictor of crash involvement for individuals with cataracts in the previous five years.23

Useful field of view (UFOV). Unlike conventional visual field measures, UFOV assesses higher-order visual processing skills such as selective and divided attention and visual processing speed under increasingly complex visual displays. Thus, it more closely approximates the complexity of driving as a visual task.

As we age, our ability to process visual information slows. While not a linear progression, this slowing makes driving in complex environments more difficult. UFOV testing can be valuable in determining which at-risk drivers with normal or near-normal visual acuity are no longer able to process visual information in a timely manner to allow for safe driving (Case 3).

However, research shows visual processing training over several hours using UFOV testing with preset criteria for success can improve not only UFOV test performance, but also the driving performance of persons older than 55. Preset criteria of 10 training sessions over five weeks resulted in an approximately 50% lower rate of at-fault motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) during the subsequent six years compared with control group.25-28

Clinical Steps

The American Medical Association’s (AMA) Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling of Older Drivers recommends that clinicians assess all risk factors when evaluating drivers older than 65, including vision, cognition and motor skills.24 For example, a clock drawing test is an easy test of cognition, and UFOV is an excellent tool to use to assess cognition as it relates to fitness to drive.29 If concerns exist in any of these areas, it recommends a referral to the state DMV/DOT for a formal driving assessment.

When examining patients of driving age, clinicians should ask the following questions, regardless of the patient’s current level of visual functioning. Your patient’s answers may surprise you:

- Do you drive an automobile? If so, are you driving at night or only during the day? Do you drive only close to home, or are you driving both in town and on the highway? (For example, they may be driving at night, when they are only visually qualified to drive during the day. If you don’t ask, you won’t know to tell the patient they are not visually qualified to drive at night according to state law.)

- Do vision problems cause you to be fearful when driving?

- During the past six months, have you made any driving errors? (e.g., an at-fault motor vehicle accident related to the patient not seeing someone or not judging distance correctly.)

- Is your mobility affected by your vision? (If your patient is struggling to find their way to the exam chair or has difficulty getting through the doorway, it is hard to imagine that they can safely operate a motor vehicle.)

Patients come to us because of the quality of care we provide, which includes giving honest information about their vision and ocular health. As optometry’s scope of practice continues to expand, we share the burden of not just the accurate and timely diagnosis of ocular disease, but also the effect that disease may have on visual function. If your patient develops visual or cognitive changes that could affect their ability to safely operate a motor vehicle, it is your professional responsibility, and legal duty, to share that information with your patient.

Case 3

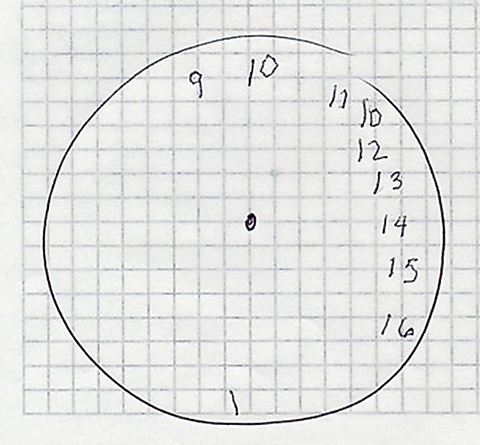

A 56-year-old male presented with a chief complaint of increasing difficulties over the past three months with both clarity and tracking when reading. He noted that he was losing his place frequently as he read from line to line and column to column. In addition, his wife said she refused to ride with him because his driving was “scary.” His BCVA was 20/20 OD/OS, and his ocular health evaluation and VFs were unremarkable. He was referred to a neuro-ophthalmologist for a positron emission tomography scan, which revealed the left occipital and parietal occipital lobes had more atrophy than the right, out of proportion to the patient’s age. He was diagnosed with the visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease (VVAD), and his wife questioned whether he was safe to continue driving. UFOV testing found he had nine times slower visual processing speed, five times slower divided visual attention skills and severely delayed selected visual attention skills—thus, he was at a high risk for an automobile accident. Based on these findings, he was advised to retire from all driving immediately. |

Assistive Technology

Currently, in 43 states , the acquisition of a bioptic telescope—a hands-free, spectacle mounted device—is the only way an individual with visual acuity less than 20/70 can attempt to qualify for driving privileges.30 However, research has yet to provide definitive data on the risks and benefits associated with this assistive technology, and the topic is surrounded by controversy. One report of 300 bioptic drivers found the biggest challenge with reduced vision (binocular acuity less than or equal to 20/200) was reading street signs—they had no problems seeing other traffic, people or animals when driving.31 In the past, practitioners felt that when a bioptic telescope is fit on one eye and appropriate training is performed, the user can maintain peripheral awareness with their fellow eye when viewing through the telescope for wayfinding such as reading street signs.

While bioptic telescopes are only used for a small percentage of driving time (1% to 10%) for wayfinding tasks such as spotting street signs, they reduce the user’s visual field and can contribute to inattention blindness. As with cell phone use while driving, when using a bioptic telescope, the driver must attend to two tasks at once, which is difficult because of the time lag associated with switching from one activity to another. One study found as drivers switch repeatedly between tasks such as using the radio or information system, the time cost adds up, increasing inattention blindness.32 Some believe the distraction created by a bioptic telescope outweighs the visual benefits, but more research is needed to clarify whether driving with a bioptic telescope makes individuals who are visually impaired safer drivers than those who do not use a device.30

Driving LegalitiesAs clinicians, we have the duty to warn, which is a legal rationale designed to provide a means of protecting the patient from an unreasonable risk of harm.1 Duty to warn states that failure to warn a patient of conditions that create a risk of injury will be upheld as a cause of action against eye care providers when it can be shown that the failure to warn is the proximate cause of an injury. All of this jargon means that if an individual with a visual impairment has a motor vehicle accident related to their reduced vision, they can hold their eye care provider responsible for the accident. In this case, the patient can argue that they had insufficient warning of their impairment, and because of their impairment, their operation of a motor vehicle or other machinery resulted in an injury. Thus, you should warn patients whose vision no longer legally qualifies them to operate a motor vehicle to abstain from driving and note this in the patient’s record. 1. Classe JG. Clinicolegal aspects of practice. Southern Journal of Optometry. January 1986;IV, I. |

Today’s audible GPS devices provide these patients a readily available and significantly cheaper option compared with a bioptic telescope. A GPS device can allow the driver to focus more attention on the road and the traffic around them and less time attempting to read street signs.

Based on our clinical experience evaluating hundreds of patients with vision loss in the 20/71 to 20/199 range, many continue to drive safely for decades in Iowa, where bioptic telescopes are not permitted to gain licensure. Today, all of our patients with impaired vision use a GPS system in lieu of their bioptic telescope.

Of course, if a person feels a bioptic helps them drive more safely, they should be allowed to use it. Clinicians should carefully discuss the pros and cons with patients who are visually impaired, and counsel them appropriately on their options when it comes to assistive technologies behind the wheel.

In general, a person’s fitness to drive cannot be determined by their age, VA or VF alone. The functional manifestations of various ocular conditions and an individual’s ability to compensate for any visual impairment varies widely. We must use our knowledge and tools to assess competency to drive or refer to a driver rehabilitation specialist for additional assessment.

We are responsible for helping our patients understand when their vision falls below the state’s standards and how that will affect their driving privileges. At the same time, we need to serve as advocates for those with reduced VA or reduced VFs who have the compensatory skills to continue driving safely, despite those reductions. Finally, we need to advocate for standardized VA and VF requirements on a national level, so that individuals who are visually impaired have the same ability to demonstrate they can safely operate a motor vehicle, regardless of their home state.

Dr. Wilkinson is a clinical professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine. He is the director of the institution’s Vision Rehabilitation Service and a faculty member of the University of Iowa Institute for Vision Research and the National Advanced Driving Simulator.

Dr. Shahid is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine, where she provides vision rehabilitation and primary eye care.

1. Wilkinson ME. Driving with a visual impairment. INSIGHT. 1998;23(2):48-52. |