|

A 32-year-old African-American female presented to the office in January with complaints of fluctuating vision and blurriness in both eyes that tended to wax and wane. The symptoms started approximately two weeks earlier, and had a slightly progressive nature to the intensity and duration of the visual disturbances, prompting her urgent visit.

Four years earlier we diagnosed her with ocular hypertension. Her intraocular pressures (IOPs) were in the mid 20s and she had a positive family history of glaucoma. She was myopic, correctable to 20/20 OD, OS and OU, with otherwise normal ophthalmic findings. She was lost to follow up until the most recent presentation.

When she presented in January, she was somewhat worried about glaucoma, given our previous visit when the condition was discussed, her lack of interim follow-up and the fact that several family members have glaucoma—one of which apparently has suffered significant vision loss. Her medications included: Lasix (furosemide, Sanofi Aventis), losartan, Sprintec (norgestimate and ethinyl estradiol, Teva), Orencia (abatacept, Bristol-Myers Squibb) and Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine, Sanofi). She reported no known allergies to medications. She started taking Plaquenil only a year earlier and her rheumatologist had told her that she needed to have a baseline ophthalmic examination, which she didn’t schedule.

Her complaints were difficult to verbalize, other than transient blur in both eyes that lasted anywhere from 10 minutes to as long as three hours, with no particular pattern to their onset. She experienced mild headaches temporally on the right side more than the left that sometimes accompanied the blurry episodes. These symptoms were new and her medication regimen was stable for approximately one year, meaning that there were no new medications introduced that may have precipitated the complaints.

|

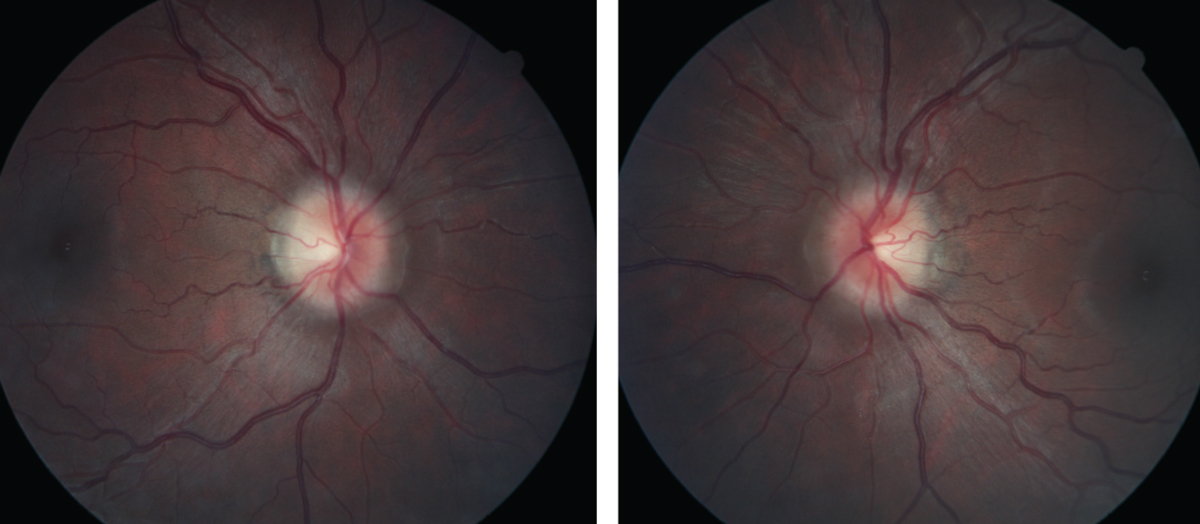

| Figs. 1 and 2. At left, the patient’s right fundus as it appeared on her initial, urgent presentation. At right, her left eye, also at initial presentation. Note the “C” shaped halo shadowing in both the right and left eyes, with the temporal neuroretinal rim essentially intact. Click images to enlarge. |

Examination

Entering and best-corrected visual acuities were 20/25- OD and 20/20-2 OS. Refractively, she was in the -7.50D range OU, similar to her last refraction several years earlier.

A slit lamp examination of her anterior segments was essentially unremarkable. Her corneas were clear, her anterior chambers were deep and quiet, and anterior chamber angles were wide open at the slit lamp. Her irides and crystalline lenses were clear in both eyes. Applanation tensions at 3:30pm were 25mm Hg OD and 26mm Hg OS. Pachymetry readings were 525µm OD and 533µm OS, which were similar to previous measurements. Prior to dilation, threshold standard automated perimetry was performed, and there were scattered areas of missed points in both eyes, with reasonable reliability indices. However, the field defects were not identifiable other than scattered generalized depression.

The patient was then dilated in the usual fashion with 1% tropicamide and 2.5% phenylephrine. Through dilated pupils her anterior vitreous was unremarkable. The macular evaluations of both eyes were also unremarkable, as were the retinal vascular appearances. Her optic nerves were characterized by small cups, approximately 0.25x0.25 OD and 0.30x0.35 OS, but her neuroretinal rims were elevated, especially nasally. There was slight asymmetry in the neuroretinal rim elevation, but both the right and the left nasal neuroretinal rims were elevated and markedly different from images taken several years earlier. The clinical appearances of the discs were characteristic of disc edema modified Frisén scale stage 1 (Figures 1 and 2).1 Spontaneous venous pulsations were absent in both eyes, and there was no record of their presence or absence at the earlier visit.

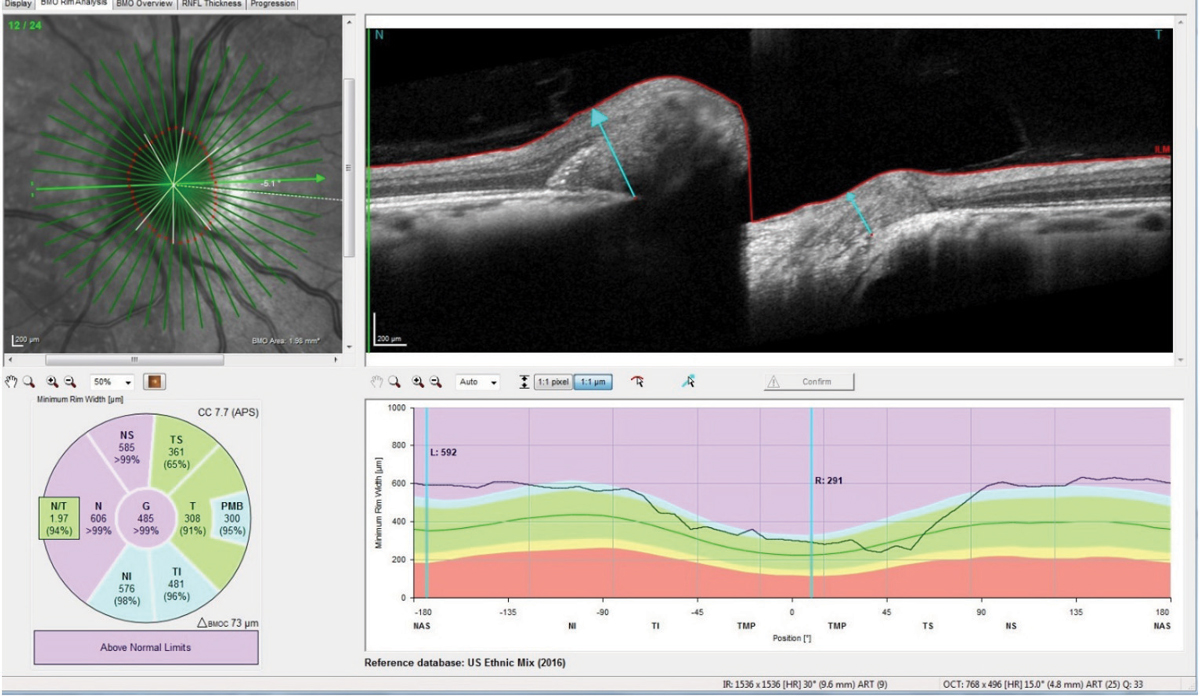

Her temporal neuroretinal rims were intact bilaterally, with no evidence of edema or swelling. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) optic nerve scans, as well as macular OCT scans, were obtained (Figure 3). The macular scans, and in particular the ganglion cell layer scans of both maculae, were entirely normal. The perioptic retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) circle scans were also essentially normal, though the innermost RNFL circle scan did demonstrate slight increased thickness to the superior, nasal and inferior RNFL sectors, as compared with the reference data base. The 4.1 and the 4.7 circle scans were entirely normal, indicating that the apparent swelling of the neuroretinal rim did not extend from the center of the optic nerve too far outward. However, the radial optic nerve scans, as well as the optic nerve raster scans, did in fact demonstrate bilateral disc edema with anterior bowing of the Bruch’s membrane and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) complex, especially nasally.

|

| Fig. 3. Note the anterior deflection of the Bruch’s membrane/RPE complex nasally in the patient’s right optic nerve, consistent with elevated retrolaminar pressure, and disc edema due to elevated intracranial pressure. Click images to enlarge. |

Discussion

This patient presented with worries associated with visual disturbances she attributed to the possibility of glaucoma. In fact, the clinical picture was just the opposite; rather than elevated IOP being the cause of her complaint, the picture was more suggestive of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP).2

Certainly, she does carry risk factors for developing glaucoma, but we are not looking at that condition here. In reviewing her medications list, as mentioned, there were no new medications introduced in the past year, and disc edema is not generally associated with the medications she was currently taking. Her macular OCT scans, as well as her general slit lamp macular evaluations, indicated that there were no visible effects from the Plaquenil use. A review of her headache history revealed nothing that raised any red flags. She did admit that she had gained about 25 pounds since our last visit. She was approximately 5’6” and weighed 165lbs.

Given the presentation, she was worked up in the usual fashion of a patient with bilateral disc edema, with emphasis given to several possible etiologies, with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and dural venous sinus thrombosis at the top of the list. I ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance venography (MRV), and she was scanned about four days after the initial presentation. The MRV was normal, as was the MRI. There was no displacement of the cerebral structures, and given no trauma history, cerebral bleeds were not very likely.

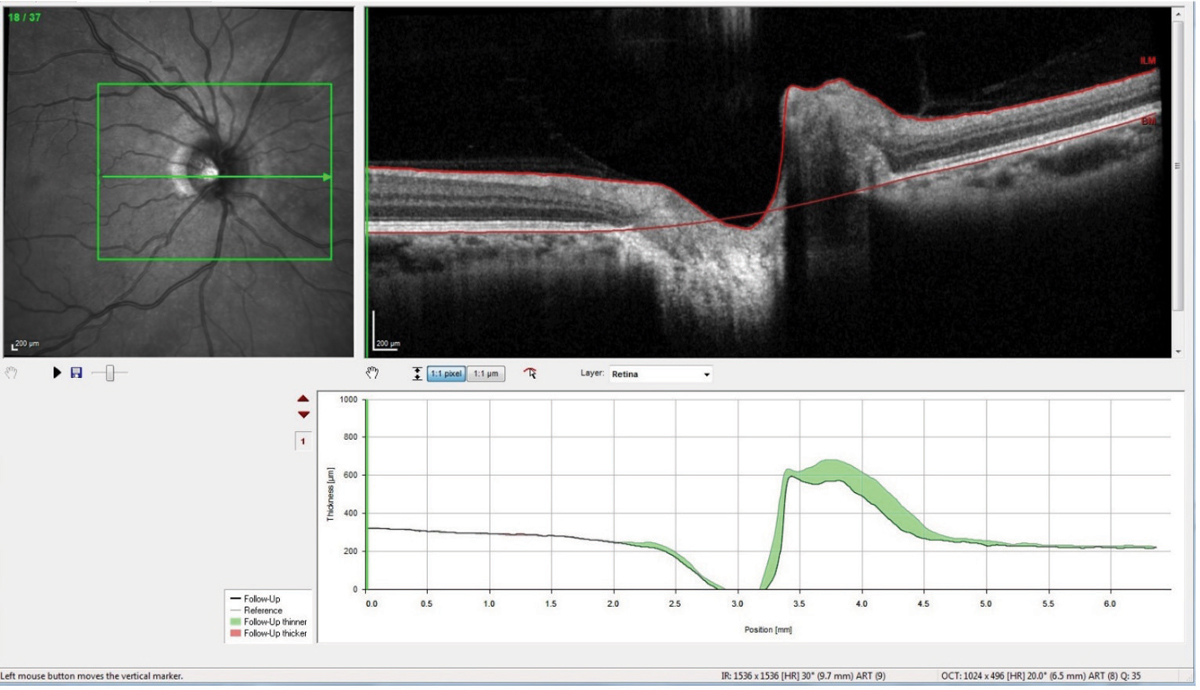

Interestingly, though a lumbar puncture (LP) is in order for this patient, in the area in which I practice, most neurologists have ceased performing LPs, and neurology consults are exceedingly difficult to obtain short of an emergency consult. Ultimately, I decided that the LP was not critical to the case at this point, and I began a regimen of 500mg Diamox sequels (acetazolamide, Duramed Pharms Barr) BID along with a dietician consult. She was scheduled for follow-up and has complied with the medication regimen and follow-up schedule. Thirty days after initiating the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, repeat scans of her optic nerves show reduction in the disc edema (Figure 4).

So why is a case like this discussed in a Glaucoma Grand Rounds column? What relevance does it have to glaucoma, other than the patients risk for developing glaucoma? Well, the answer lies in the anatomy of the optic nerve. Traditionally, we think of glaucoma as a disease where the IOP exceeds a healthy level to the point that optic nerve perfusion is compromised, resulting in compromise to the individual ganglion cells. This can happen when IOP is significantly elevated, or conversely when optic nerve perfusion pressure is greatly reduced, or anywhere in between. Which makes for a sliding scale for what is considered an IOP that is ‘too high.’

|

| Fig. 4. This optic nerve raster OCT scan is a follow-up showing significant reduction in the nasal neuroretinal rim swelling, as evidenced by the green areas in the change analysis. Click images to enlarge. |

Under Pressures

But that is only half the picture: what is happening anterior to the lamina cribrosa, to IOP and to the blood supply to the individual ganglion cells, or axomplasmic flow through the individual ganglion cells. That is but one consideration. The other consideration is what is happening behind the lamina cribrosa. Specifically, in the subarachnoid space around the optic nerve, anteriorly to the lamina cribrosa. And this is the area of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics.

Cerebrospinal fluid pressure is exerting pressure on the lamina anteriorly, whereas intraocular pressure is exerting pressure on the lamina posteriorly. And trapped in the middle between these two pressure gradients are the ganglion cells we exhaustively examine in the context of glaucoma. This is the basis of the translaminar pressure gradient that needs to be considered in all patients with glaucoma and optic nerve disease.

Many factors can affect ICP, aside from the obvious things like space-occupying lesions, cerebral hemorrhages and IIH.3 Sleep apnea, cardiovascular diseases and body weight can all affect ICP in one way or another. And when you alter ICP, you are exerting influence on the retrolaminar optic nerve. Furthermore, just as IOP tends to have diurnal variations, so too does ICP. Sometimes those diurnal fluctuations can work in tandem and somewhat “protect” the optic nerve, whereas other times, they can work antagonistically and negatively affect the optic nerve health (for example, when IOP is high and ICP is low).

In the NASA space station program, research shows individuals who remain in a zero gravity environment for extended periods of time, develop disc edema.4 Researchers believe this is directly tied to the effects of zero gravity to ICP, and the asymmetry between the ICP and the IOP.4

As for our patient, weight reduction and temporary use of Diamox is resulting in normalization of her optic nerve appearance. Once this is behind us, then we continue moving forward concentrating on the anterior side of the lamina cribrosa, and her risk of developing glaucoma.

1. Frisén L. Swelling of the optic nerve head: a staging scheme. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982;45(1)13-8. |