|

A 26-year-old female presented with a chief complaint of missing spots in her vision in the right eye, which she first noticed while watching television. She had a two-year history of one to two headaches a week that was unchanged. She had no ocular pain and no headache at the time of her vision loss. Her vitals at the time of exam included a blood pressure of 151/90 and a pulse of 95 BPM. Her general health and previous ocular history was noncontributory.

On examination, her visual acuity measured 20/200 OD and 20/20 OS. Her pupils were equally round and reactive to light. An afferent pupillary defect was seen in the right eye. On color vision testing, she had red desaturation in the right eye by 50%, compared with her left eye, and had decreased light brightness compared with the left eye. She was unable to decipher the test plate on Ishihara with the right eye and had normal color vision in the left eye. Her extraocular motility was normal, and confrontation visual fields in the right eye were significant for a central scotoma with preserved peripheral vision. The left confrontation visual field was full. The slit lamp exam was unremarkable and intraocular pressure was normal.

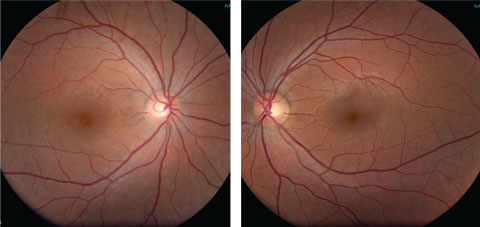

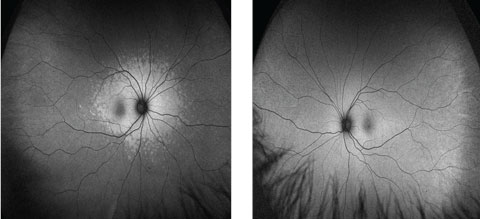

On dilated fundus exam, the optic nerves appeared normal. There was no disc edema in either eye, and the macula also looked normal, although there was a reduced fovea light reflex in the right eye (Figure 1).

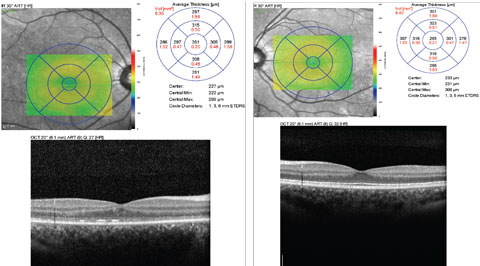

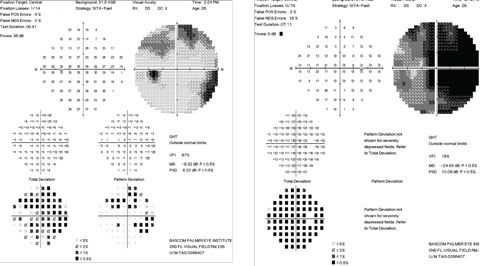

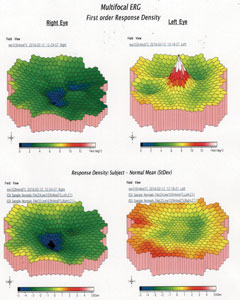

An OCT (Figure 2), visual field (Figure 3) and multifocal electroretinography (ERG) (Figure 4) and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) (Figure 5) are available for review.

|

| Figs. 1a and 1b. Fundus photos of our 26-year-old female patient’s right and left eyes at clinical presentation. Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. What is the significant OCT finding?

a. Loss of foveal contour.

b. Thickening of the nerve fiber layer in the macula and optic nerve.

c. Disruption of inner segment/outer segment junction and thinning of outer nuclear layer.

d. Accumulation of fluid.

2. What does the multifocal ERG show?

a. It is normal.

b. A choroidal excavation.

c. A central depression in the right and normal foveal peak in the left.

d. A normal right eye and hypersensitivity of the left.

3. What is the likely diagnosis?

a. Malingerer.

b. Cone-rod dystrophy.

c. Acute zonal outer occult retinopathy.

d. Stargardt’s macular dystrophy.

4. What is the expected prognosis?

a. Stabilization of the visual field by six months.

b. Some improvement of the inner segment/outer segment integrity.

c. Persistent visual defect, including scotoma, usually persists.

d. All of the above.

|

| Fig. 2. Can you identify any significant findings in either the patient’s right (at left) or left macula using these SD-OCT images and data? Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Based on the patient’s symptoms and testing, we suspected she had acute zonal occult outer retinopathy (AZOOR). This condition has an unconfirmed etiology, but investigators suspect either a viral or autoimmune cause.1 AZOOR, first described in 1992, shows a predominance in young women and is characterized by acute photopsias, scotomas and ERG abnormalities with minimal or no fundus findings, minimal or no vitreous cell and normal fluorescein angiography (FA).1,2 Investigators found 20% of patients had a viral prodrome.1 A majority of these patients have vision 20/40 or better, with only 5% of eyes presenting with 20/200 or worse.1 Changes can be detected on FAF and on OCT that correlate with the field loss and diminished ERG. Due to our suspicion, we acquired mfERG, FAF and FA. Our patient had significant visual field loss in the right eye that correlated with a central depression on her mfERG (Figure 3). The FAF also showed corresponding increased hyperautofluorescence around the optic nerve and macula (Figure 4). This is common in AZOOR, indicating damage to the RPE.3 The OCT showed marked disruption of the inner segment/outer segment junction in the right eye, suggesting photoreceptor involvement, a consistent finding in AZOOR (Figure 5).3 These abnormalities were all in the setting of a normal fundus exam (Figure 1) and FA. This testing confirmed the diagnosis of AZOOR. As in this case, multimodal imaging is critical for establishing diagnosis.

|

| Figs. 3. Our patient’s visual field test results at initial clinical presentation. Note the findings in the left eye (at right). Click image to enlarge. |

Management

There is no established treatment for AZOOR, and the natural course of AZOOR is highly variable. Only 26% of cases show visual improvement, and 13% had visual deterioration, according to researchers.1 Most cases reported had visual field defects that stabilized by six months.1,4

|

| Fig. 4. What information about the macula’s health can be gleaned from these multifocal ERG graphics of the right and left eyes? Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment options include steroid therapy, antiviral therapy and noncorticosteroid immunosuppression. All therapies show limited success.1,5 The most commonly used treatment that has shown possible benefits is steroid therapy.1,5 Some studies show that early initiation is critical.5 These studies suggest that AZOOR has an inflammatory component involving the photoreceptors and that early initiation of steroid therapy may have a better potential to reverse the natural course.1,5

The difficulty with steroid therapy is that confirmation of the diagnosis often takes significant time and the results become less beneficial with delayed treatment.5

With our patient, steroid treatment (40mg oral prednisolone daily) and antiviral therapy of 1g Valtrex (valacyclovir HCL, GlaxoSmithKline) daily was initiated seven days after the start of symptoms. At her six month follow-up from presentation, her exam findings were stable with the exception of visual acuity improvement in the right eye to 20/30 from 20/200, and resolution of her RAPD. She still has a persistent central scotoma, but the patient appreciated subjective significant field improvement. Her FAF showed improvement as well with a decrease in hyperautofluorescence around the macula and nerve. On OCT of the macula, the integrity of her inner segment/outer segment junction had improved.

Leslie Small, OD, practices at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

|

| Fig. 5. Note that the right eye (at left) shows patchy hyperautofluorescence around the optic nerve and macula, while the left shows the normal uniformly diffuse autofluorescence in these FAF images. Click image to enlarge. |

|

1. Monson DM, Smith JR. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:23-35. 2. Gass JD. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. Donders Lecture: The Netherlands Ophthalmological Society, Maastricht, Holland, June 19, 1992. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1993;13:79-97. 3. Fujiwara T, Imamura Y, Giovinazzo VJ, Spaide RF. Fundus autofluorescence and optical coherence tomographic findings in acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. Retina. 2010;30:1206-16. 4. Gass JD, Agarwal A, Scott IU. Acute zonal occult outer retinopathy: a long-term follow-up study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:329-39. 5. Chen SN, Yang CH, Yang CM. Systemic corticosteroids therapy in the management of acute zonal occult outer retinopathy. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:793026. 6. Matsui Y, Matsubara H, Ueno S, et al. Changes in outer retinal microstructures during six month period in eyes with acute zonal occult outer retinopathy-complex. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110592. |