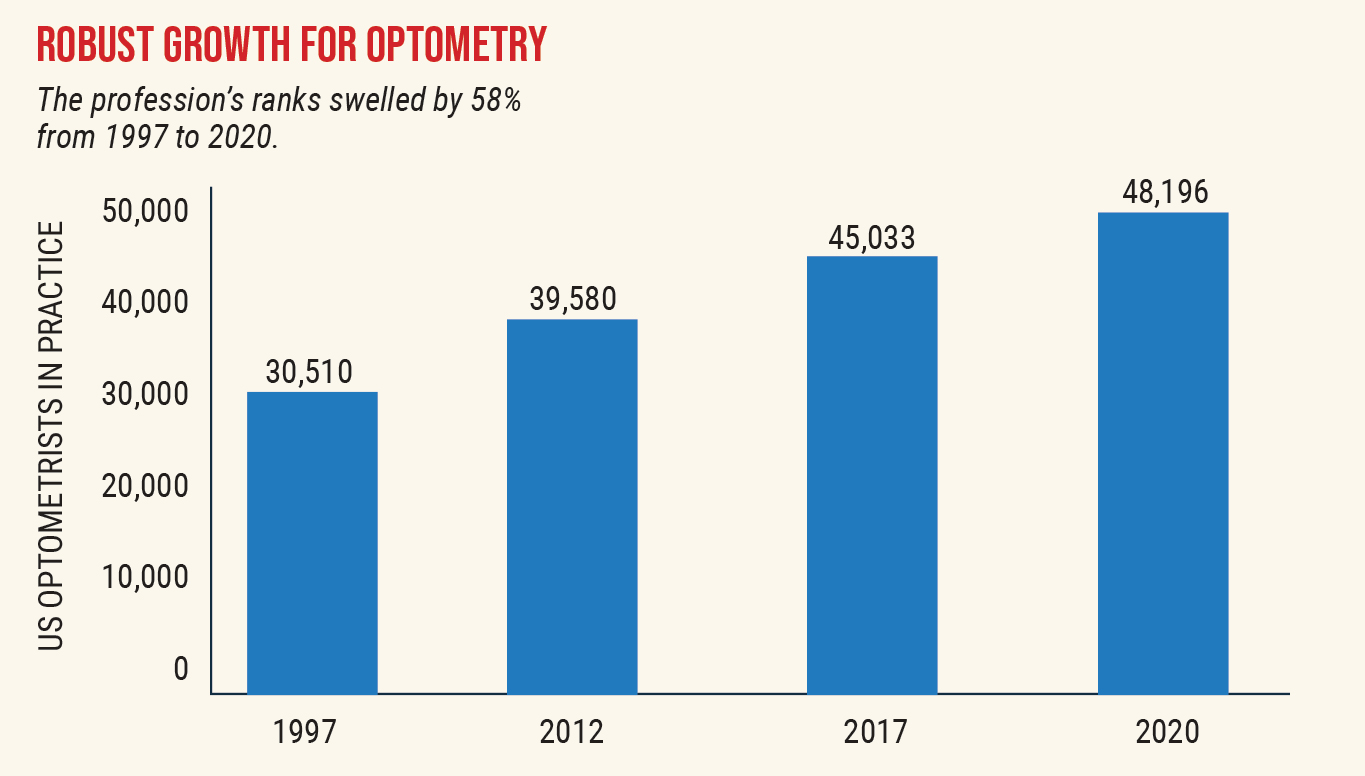

Over the next decade, the optometric workforce is projected to experience growth of 1.4% each year, a continued shift toward a female OD majority and a more limited additional capacity for the profession to expand than previously suggested, a recent national survey suggests.1

The investigation, based on 2017 data and published in Optometry and Vision Science, also found a lack of diversity in the profession. Minorities are poorly represented in optometry, which the authors cite as concerning and a barrier to care. Specifically, only 3.8% of respondents self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, 0.4% as Black/African-American and 0.2% as Native American.

“This is clearly much lower than the overall population’s makeup and hopefully is a wake-up call to our profession to encourage minority recruitment,” says Brian Chou, OD, of San Diego.

Researchers distributed the 2017 National Optometry Workforce Survey to roughly 4,000 ODs from the AOA’s database. The results reflected the responses of 1,158 optometrists.

The study found the optometric workforce is projected to grow annually by just 0.6% to 0.7% more than the United States population, and that trend should stay consistent over the next 10 years if no additional optometry programs open.

The investigation also reported some notable shifts compared with similar workforce data from 2012, published by the Lewin Group in 2014, that suggested a much higher potential for the then-current workforce to see more patients, as well as a significant disparity in productivity between men and women working in the profession.2

“We found there really weren’t significant differences when we challenged the assumption that the productivity of women wasn’t the same as men, and also, as a profession, we’ve really moved toward a more equitable and balanced workforce,” says lead researcher David A. Heath, OD, EdM, president of the State University of New York College of Optometry.

|

|

Growth in the optometric workforce has outpaced that of other medical professions. Source: American Optometric Association. Click image to enlarge. |

Women Edge Past Men as Dominant Gender

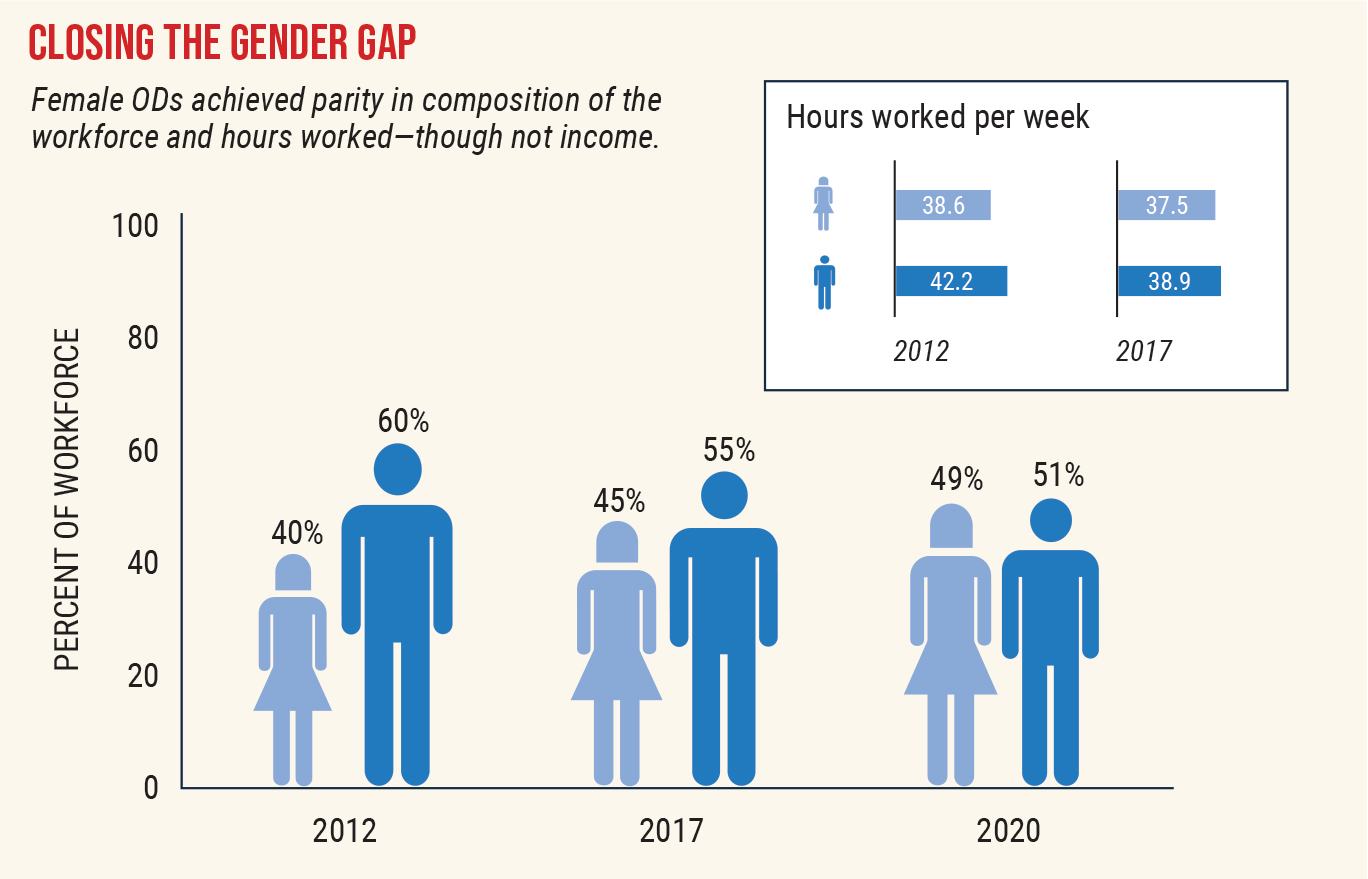

As more women enter the profession, the workforce continues to experience a shift in the male-to-female ratio, says Dr. Heath.

Female ODs represented 43% of responding doctors in the survey. In 2017, 45% of ODs in the AOA’s database were women (20,249). By January 2020, the number of female optometrists grew to 23,367 (49%). Taking into account that roughly 650 more women than men now graduate each year from optometry programs, and that most retirees currently are male, the authors predict more women than men are now actively practicing optometry in the United States.

Females Claim Majority in Optometry Schools

A few years ago, optometrist Pamela Miller of Highland, CA, lectured at her alma mater, the Southern California College of Optometry. When the longtime private practice owner looked out at the crowd of students and noticed it was predominantly female, she asked herself, “Where have all the men gone?”

Dr. Miller, who opened her practice cold 50 years ago, recalled being one of only a handful of women who attended the optometry school during the early 1970s.

After graduation, Dr. Miller was the first woman to serve on the California State Board of Optometry and the first female board member of the California Optometric Association. Still, despite being at the forefront of women entering the profession, Dr. Miller says she was denied a bank loan of $34,000 to purchase her practice initially due to her gender, despite the fact that she owned residential property and personally knew the bank loan officer.

Fast forward to today and gender discrepancies in the profession have narrowed significantly, including in optometry school enrollment.

|

For optometry, the future—and much of the present—is female. Women often make up the lion’s share of graduating classes, as seen here among Berkeley’s 2021 grads, while retirees exiting the field skew heavily male. The 2017 National Optometry Workforce Survey documents female ODs’ gains both in sheer numbers and also hours worked and patients seen. Click image to enlarge. |

In the 2017-18 academic year, there were 4,830 females and 2,294 males enrolled as full-time optometry students at US schools and colleges of optometry, including Puerto Rico, according to the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO).3 In fact, female optometry students have outnumbered males for at least the past decade.3

“Throughout our profession, entering class profiles are approximately 70% female, and have been for several years now,” says optometrist Chris Wroten, partner at the Bond-Wroten Eye Clinics in Louisiana and adjunct professor at Southern College of Optometry. “As a result, more and more female doctors of optometry are thankfully sharing their leadership skills by assuming prominent roles in their state associations and within the AOA and other optometric organizations.

Dr. Wroten served as an expert panel member for the 2012 AOA/ASCO Eyecare Workforce Study and is currently the moderator of the AOA Presidents’ Council meetings, president of the Louisiana State Board of Optometry Examiners and Chair of SCO’s Board of Trustees. He also supervises his practice’s primary care and ocular disease residency program and works with student externs.

In his numerous roles in the profession, Dr. Wroten believes optometry is following the same trend as medicine and dentistry—the gender pay gap still exists but is showing signs of closing, while more and more women, and fewer men, are applying to medical, dental and optometry school.

“The women in our profession I’ve been blessed to know and work with are all extremely passionate about optometry, care deeply for their patients, have an unsurpassed work ethic and see every bit as many patients as their male counterparts, while still striking an appropriate work-life balance,” says Dr. Wroten, who works with several female doctors of optometry at his practice, including his wife.

Productivity Assumptions Questioned

It has commonly been assumed that female ODs work fewer hours than men and see fewer patients; however, the current survey refutes this theory and illustrates an evolving and equitable workforce, the authors note.

Looking at weekly work schedules, women and men logged about the same number of hours: 37.5 for women vs. 38.9 for men. This difference wasn’t significant and is notably smaller than the difference reported in the Lewin study (women: 38.55 hours; men: 42.15).

Similarly, the gender gap narrowed a bit in the number of weeks worked per year. In 2017, women reported working an average of 47.7 weeks while men worked 48.5 weeks annually. In the 2012 Lewin data, women reported working about 46.7 weeks a year vs. 47.8 weeks a year for men.

Considering productivity, women and men both saw essentially the same number of patients per hour: 1.97 for women vs. two for men. This is in contrast to the Lewin study, which reported lower productivity in women based on patients they saw per hour: 1.63 for women vs. 1.89 for men.

In 2017, 77% of women and 78% of men reported they would prefer to have the same or fewer patient care hours. However, there was an increase in the number of women who desired to decrease hours, from 10% in 2012 to 25% in 2017.

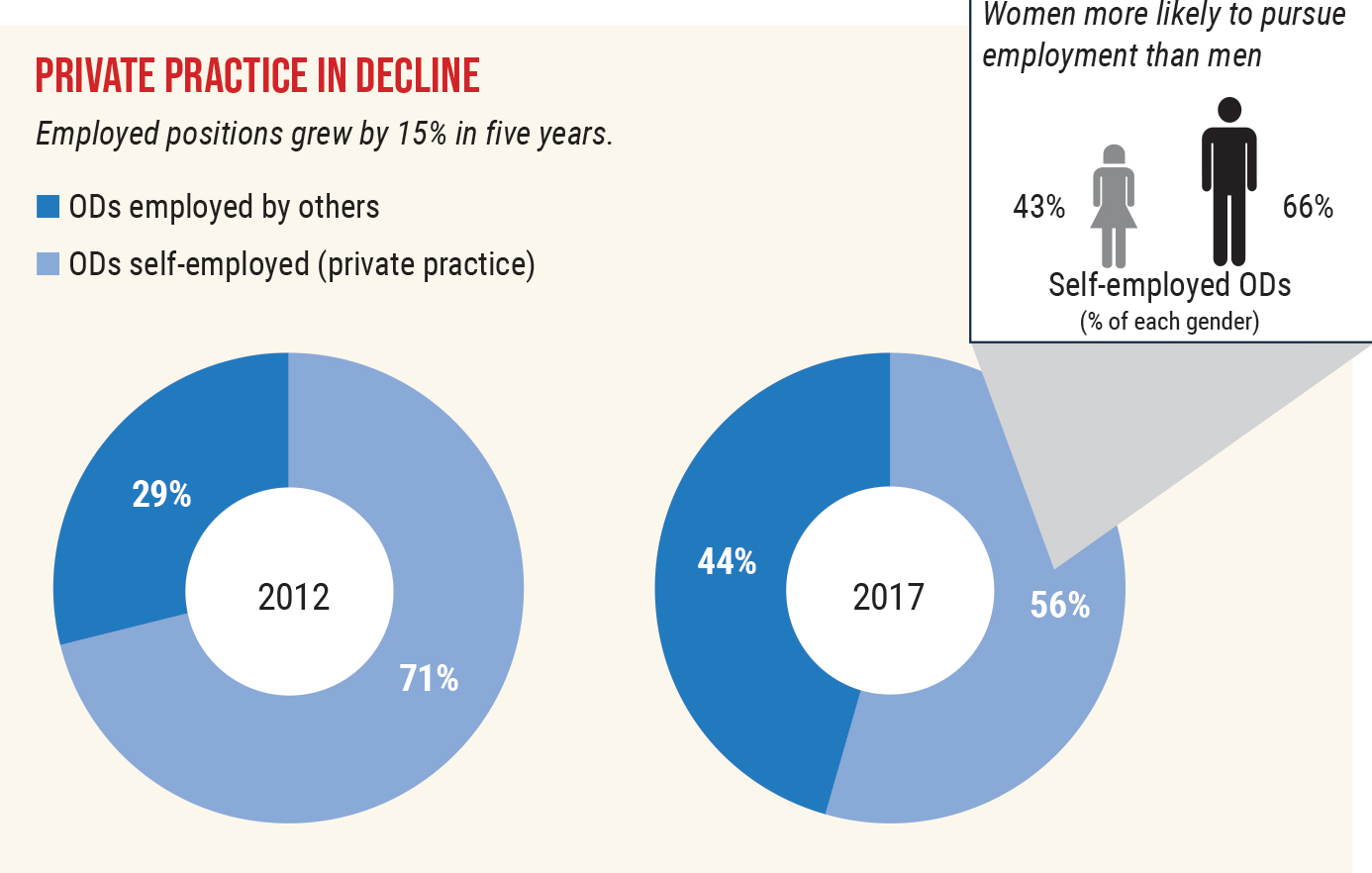

Also of note in gender trends: women tended to be employed rather than self-employed and earned less as a whole.

|

|

Women have made steady gains in the makeup of the optometric workforce and are on track to become the majority of practicing ODs in short order—if they haven’t already. Source: American Optometric Association. Click image to enlarge. |

Women Still Lag in Pay

Overall, a slight majority of optometrists reported income between $100,000 and $199,999, with more female optometrists than male making less than $100,000. Perhaps not surprisingly, those ODs who made more than $200,000 were most likely to be self-employed (23%).

One reason for the apparent salary differences between genders may simply be that male responders tended to be older, more experienced and owned their practices, Dr. Heath says.

Beyond optometry, some recent studies affirm the pay gap still exists between genders across various medical disciplines. One investigation that evaluated salaries among physicians with faculty appointments at 24 US public medical schools found an absolute annual pay gap of $51,315 between men and women.4 After adjusting for factors such as age, years in rank and specialty, the annual disparity was $19,878.4

Another research paper, published in 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine, found female primary care providers (PCPs) generated nearly 11% less annual visit revenue than male doctors in the same practices, yet they spent more time with patients per visit, per day and per year.5 The revenue gap was driven entirely by differences in visit volume, which were only in small part explained by the fewer days that female PCPs saw patients.5

Taken together, these results suggest that the differences in time spent with patients may be a contributor to the gender pay gap, with female physicians effectively generating 87% of what male physicians generate per hour of direct patient care, the authors said.5

“Honestly, I think the wage gap is still there because we are women,” says Jennifer Dattolo, OD, FCOVD. “I think in most professions, men make more than women do for the exact same job.”

Dr. Dattolo, who is a partner at her practice in Woodstock, GA, says she feels society devalues women to some degree, and this still lingers in the profession. “I do think men and women are working close to the same hours per week and seeing the same number of patients. And hopefully the pay gap between men and women will close and become equal in the very near future,” she says.

Since the majority of graduating doctors from optometry school are currently female and many new grads carry a significant debt load, Dr. Miller speculates an employed, salaried position might be a more attractive option than pursuing an ownership opportunity, which may factor into the pay discrepancy between genders.

“You govern your own future,” Dr. Miller says. “There are women who want to own a practice and others who want flexibility.”

Despite the pay gap, both male and female ODs also appeared to be equally happy with their jobs. Career options/professional growth satisfaction ranked in at 65% for both male and female ODs, in the current survey.

Additional “Capacity” Questioned

Respondents were also asked to assess their ability to take on more patients in their practice, which was defined as “additional capacity.”

The Lewin study reported that optometrists could, on average, see about 20 more patients a week, or 32% more patients annually. In 2014, this finding fed controversy about whether there was a need for more optometrists and more optometry schools, and essentially split the profession into two camps over the issue, Dr. Heath says.

Dr. Chou remembers the impact of the Lewin study and how the results instigated a heated discussion in the profession on whether there were too many optometry schools minting too many ODs.

This latest workforce survey’s growth findings of 1.4% annually (0.6% to 0.7% greater than the US population) suggests an adequate workforce supply, with a small surplus created each year, Dr. Chou suggests.

“This is contrary to the doom-and-gloom scenario of too many optometry schools and too many optometry graduates,” Dr. Chou adds. However, these workforce surveys did not consider technological advances that may reduce consumer demand of traditional optometric services, Dr. Chou suggests.

“For example, there is a proliferation of self-administered online vision tests with remote eyeglass and contact lens prescription renewal,” Dr. Chou notes. “If optometric refractive services erode without the corresponding expansion into other services like medical eye care, our profession can still find itself with far too many optometrists and not enough patients seeking care, irrespective of what the latest workforce survey says.”

The Lewin survey’s question on this topic was effectively appointment book-based, reflecting the sum of the empty slots and the number of no-shows in an OD’s appointment book, Dr. Heath explains. “Since some optometrists may add more appointments to compensate for no-shows—and there will always be no-shows—the 32% figure was an inflated estimate,” he adds.

There was also no exploration as to whether the responders wanted to see more patients. As such, the current study asked the question differently, by querying ODs on how many more patient exams they could accommodate without changing current schedules or staffing. To further validate this, the study then queried participants about waiting times for appointments and whether ODs actually wanted to see more patients.

Overall, the mean number of additional patients that reportedly could be seen by an individual provider was pegged at 9.67 per week. This number conceptually represents the additional capacity that an optometrist could see as opposed to would likely see, researchers noted. The new data indicate a likely range of additional patient capacity of 2.29 to 2.57 patients per week (5.05 to 5.65 million annually profession-wide).

The study also considered if doctors who reported they could accommodate additional patients could do so without changing their practice patterns. A total of 65% of ODs reported a wait of at least two days for a patient to get an appointment for a comprehensive eye examination, whereas 7% reported a waiting time of two to three weeks and 5% indicated a wait time of more than three weeks.

In the 2017 data, nearly two-thirds of ODs reported that their current wait times for appointments were the same as the previous year. Only 13% of practicing optometrists reported a decrease in appointment wait times, whereas 23% reported an increase.

A final question assessing the ability of the optometrist to see additional patients asked respondents to indicate if they were unable to accommodate all patients requesting appointments, provide care to all who requested appointments but were overworked, provide care to all who requested appointments (not overworked) or could accommodate more patient appointments.

About 8% indicated they were unable to accommodate all patients asking for an appointment, whereas 12% indicated they did provide services to all patients but were overworked. Notably, only one-third (33%) of respondents selected could accommodate more patient appointments.

|

|

Experts attribute the shift toward employed positions over private practice ownership to many factors, including the high cost of student loan debt for new grads and the appeal of private equity. Source: American Optometric Association. Click image to enlarge. |

Most optometrists within each group indicated they wanted their patient care hours and their non–patient care hours to remain unchanged (49% and 57%, respectively). Less than a third of optometrists in each group indicated a desire to increase patient care hours.

“I do think there are still opportunities to provide more medical eye care and for many of us to better use our staffs in the provision of care,” Dr. Wroten suggests.

Another area to consider: new technology may enhance efficiency, but in turn, could also erode some traditional modes of practice.

“However, I don’t get the impression that the demand for optometry services far exceeds the supply of optometrists, except in more rural areas where it’s becoming harder and harder to recruit new graduates to practice,” Dr. Wroten explains.

Additionally, the national applicant pool for optometry school has remained relatively flat for several years now, while the number of optometry school positions available has grown as some existing institutions increase class sizes and newer schools open.

“A host of factors, including the impacts of telemedicine, emerging technologies and the average retirement age for doctors of optometry, coupled with the quality and quantity of optometry school graduates, will ultimately determine whether demand exceeds supply or vice versa,” Dr. Wroten says.

Pandemic Disrupts Optometric Workforce Status Quo

Since the 2017 workforce study was based on doctor feedback three years prior to the pandemic, a question remains on how the new safety and social distancing requirements imposed since the onset of COVID-19 have curtailed patient visits and, in turn, impacted physician productivity.

Dr. Heath believes the most immediate impact on the workforce will be on the rate of retirement, sine he says it’s likely that a number of optometrists who were considering ending their active time in the profession over the next few years before the pandemic hit may have accelerated their decision.

Those trends will be part of the AOA’s master data file and are worth examining, Dr. Heath says. “If there is a significant increase in retirements, it would tighten the labor market for optometrists, much as it has in other health professions.”

He adds, “It’s just conjecture on my part, but until safety measures, particularly social distancing, are relaxed by various state departments of health, I’m not sure practices will see a full return in the number of patients to pre-pandemic levels. Practices are limited physically, and there is only so much you can do by changing patient flow.”

Also, staff delegation, telemedicine and new technologies can all impact efficiency and patient capacity regardless of the pandemic, he suggests.

The Drive to DiversifyEfforts are now underway to make optometry more inclusive, and Ruth Shoge, OD, MPH, wants to be sure the profession doesn’t take its foot off the gas. Although she’s encouraged by the recent momentum in this area over the past year—including the expanded number of minority students applying to optometry schools and cultural competency courses added to some curricula—Dr. Shoge, who will join Berkeley Optometry School as its inaugural Director of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging later this month, says there’s still plenty of work that needs to be done and worries that people will lose interest in efforts to invest in a diverse and culturally competent optometric workforce. “We have to keep going, and accountability will help with that.” Ten years into her optometric career, Dr. Shoge pursued her Master in Public Health degree with a concentration in Social and Behavioral Science at Temple University in order to better understand the ways in which she could best serve her community, a decision that reaffirmed her dedication to the pursuit of expanding diversity and cultural competence in the profession and addressing health disparities among underserved populations. In fact, her master’s thesis at Temple was “Social Experiences of Underrepresented Minority Optometry Students.” One barrier to minority enrollment is that these individuals often don’t see themselves reflected in the profession, she explains. As part of her master’s project, Dr. Shoge surveyed students and found most had previous exposure to optometry in their youth, including eye exams. “It makes a big difference if you actually see someone in that role, and it’s even more powerful if you see someone in that role who looks like you,” she says. Not seeing other minority students enrolled in optometry schools also poses a barrier, in addition to the financial burden of higher education, she adds.

Minority Applications RisingDr. Shoge, who will be leaving her current role as associate professor at Salus University, points to some promising news she just learned as chair of ASCO’s Diversity and Cultural Competency Committee: minority applications to optometry schools are on the rise. While there has been a 4.7% overall increase in applicants this year, almost 6% of the applicant pool is Black or African-American, a number that has traditionally hovered between 4% and 5%. Additionally, there has been an uptick in the number of Hispanic and Latino applicants: 12.6% compared to the usual 9% to 11%. “It may seem like a small number, but it’s a big difference, and it means our efforts are working,” she says. The Profession ReactsSome of these successful efforts include ASCO’s “Optometry Gives Me Life” initiative that aims to bolster interest in optometry schools, in addition to the continued minority recruitment and health care disparity initiatives of the National Optometric Association. Dr. Shoge cites another leader in this area: Black Eyecare Perspective, an organization created to foster lifelong relationships between those who identify as Black and the eyecare industry, and to create more black representation in all levels of the profession. “Black Eyecare Perspective is doing a tremendous job at creating buzz and mentorships with Black students looking to optometry as a career,” Dr. Shoge says. Corporations have also recently stepped up with donations to help support some of these initiatives, including one she oversees: Salus’s Summer Enrichment Program, which aims to improve the matriculation, attrition and graduation rates of underrepresented minority applicants through a free, five-week program. It had been on hiatus for several years due to lack of funding but has been reinstated in response to growing demand for attention to the diversification effort. Still other institutions have added cultural competency and anti-racism courses to their curricula. “One branch of our purpose is to increase the number of underrepresented minorities in optometry school, but the other part is to ensure the overall cultural competency for the entire student body. Having these courses as resources helps everyone understand that it’s an ‘all of us’ issue. All of us need to be involved,” Dr. Shoge says. Dr. Shoge was recently on a panel hosted by SUNY College of Optometry, “Race in Optometry: Accountability—One Year Later,” which was held on the same night that Juneteenth was declared a Federal holiday by President Biden and was a follow-up to three previous seminars on race in the profession. The series put a spotlight on the experiences of Black optometry students, residents, faculty and practitioners. The intent of the series was to foster a dialog that would lead to needed changes in optometric education and in the eyecare industry. Expanding Care to the UnderservedThe broadest goal in diversity and inclusion is to make sure individuals who live in underserved communities receive care, Dr. Shoge says. “I like to think about the purposes of our initiatives as short-term, intermediate-term and long-term.” The short-term goal is to increase the matriculation and graduation of underrepresented minority students, and particularly Black students. Intermediate goals include nurturing and encouraging these students to pursue leadership roles in their profession, whether in an academic, corporate or political setting. “Our long-term goals should include doing everything we can to help reduce health disparities and improve health outcomes in the communities we serve, particularly in places where we know there are poorer outcomes and more exaggerated health disparities.” She adds, “One thing we know that helps combat this is concordance, which simply means the physician and patient share some sort of cultural, social or linguistic identity.” Research has shown concordance helps improve the likelihood that a patient will seek care in the first place, trust their doctor, adhere to treatment protocols and follow up—and maybe even bring along their family, friends or neighbors to seek care,” Dr. Shoge adds. Through collective, ongoing efforts, Dr. Shoge hopes the profession will continue to make strides in diversifying its ranks—in classrooms today and exam rooms tomorrow. |

A Trend Away from Private Practice

The study also examined the current levels of employed vs. self-employed optometrists, broadly defining those who earn a salary as “employed” and not limiting the designation to those who work in a commercial practice. For example, employed optometrists could work in a university setting, hospital, community health center or in private optometry or ophthalmology practice, Dr. Heath says.

The most significant finding in this area was a substantial shift in the percentage of employed optometrists, which increased from 29% in 2012 to 44% in 2017. There was, of course, a commensurate decrease in the percentage of self-employed optometrists from 71% to 56% in 2017, Dr. Heath says.

Dr. Chou finds it concerning—but also not surprising—that there is a trend toward employed vs. self-employed work settings.

“With private equity activity ramping up significantly since 2017 when the latest survey was collected, we can expect an even greater number of ODs finding themselves in employed situations as time moves forward,” Dr. Chou says. “While there are multiple interpretations of what underlies the trend toward employment, my take is that it is increasingly difficult to own a practice, which leads to more aspiring for employment.”

Minorities Still Underrepresented | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 92% |

| Data missing | 4% |

| Race | |

| American Indian | 0% |

| Asian | 12% |

| Black/African American | 0% |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1% |

| White | 81% |

| Other | 0% |

| Data missing | 6% |

| Source: American Optometric Association | |

Both studies generally found employed and self-employed optometrists worked the same number of hours and were equally productive and satisfied in their roles. However, the employed optometrists saw significantly more patients per week on average than those who were self-employed (58 vs. 54).

The trend toward an increasing number of employed optometrists is also mirroring what is occurring in other health care specialties, as large health care systems expand and private equity acquires more practices and employs their previous owners, Dr. Wroten suggests.

“It also seems like a higher percentage of recent optometry school graduates are content to seek an employment relationship vs. purchasing an existing practice or starting one from scratch, some of which may be driven by escalating student debt,” he says.

Opportunities for ODs to work for industry have also increased, Dr. Wroten explains.

Much of the debate about whether there is a surplus or deficit in the capabilities of optometrists to meet the needs of the American public is purely speculative and can be influenced by many factors, Dr. Heath suggests.

“There is often an assumption that at any given moment, the demand for eye care is equal to the supply and that future projections, if not equal to population growth, will result in an over- or under-supply,” Dr. Heath explains.

To accurately project, it would be necessary to know if there is currently an unmet need (demand), in addition to what is being provided.

“This study didn’t examine the demand for optometric services, so we need to be cautious on this issue,” Dr. Heath adds.

Next Steps

Dr. Heath says he believes it’s critically important for the profession to continuously monitor the optometric workforce for not only overall supply and demographic shifts but also for trends that impact national, state and local health care policy. The lack of publications in peer-reviewed journals addressing these issues is startling and puts the profession at a significant disadvantage in its ability to advocate for and affect public health policy, he adds.

1. Heath DA, Spangler JS, Wingert TA, et al. 2017 national optometry workforce survey. Optom Vis Sci. 2021;98(5):500-511. 2. Lewin Group. Report on the 2012 National eye care workforce survey of optometrists. Falls Church, VA: The Lewin Group; 2014. 3. The Future is Female. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org/news/inside-optometry/aoa-news/the-future-is-female?sso=y#:~:text=In%20the%202017%2D18%20academic,Colleges%20of%20Optometry%20(ASCO). March 17, 2019. Accessed June 7, 2021. 4. Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in U.S. public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. 5. Ganguli I, Sheridan B, Gray J, et al. Physician work hours and the gender pay gap—evidence from primary care. N Eng J Med. 2020 Oct 1;383(14):1349-1357. |