|

A 65-year-old man presented with unilateral blurred vision, headaches and periorbital swelling. He reported that the fullness and swelling around the right eye had been present for over a year but that the floaters, tearing and blurred vision in the same eye were recent developments. His mild headaches localized over the right temporal and periorbital regions. His medical history was unremarkable, and he endorsed daily multivitamins with no other medications.

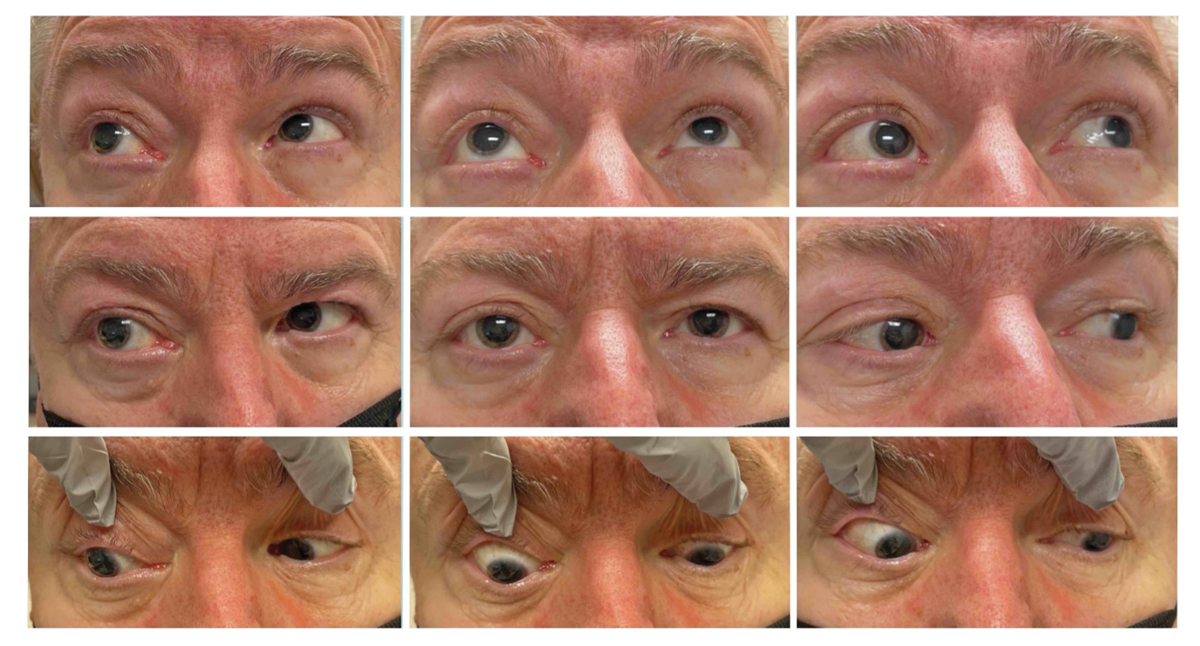

On examination, his vision corrected to 20/40 OD and 20/30 OS. His intraocular pressures were 23mm Hg OD and 18mm Hg OS. Pupillary examination revealed pupils equal in size but an afferent pupillary defect (APD) OD. He correctly identified 11 out of 14 color plates in each eye but noted a 50% subjective brightness desaturation in the right eye compared with the left with a transilluminator. Right eye extraocular motilities revealed abduction (12∅ esotropia on right gaze), adduction (8∅ exotropia on left gaze) and supraduction deficits (3∅ hypotropia on right upgaze) (Figure 1). Exophthalmolmetry revealed 7mm of proptosis OD, with notable fullness of the tissue surrounding the eye (Figure 2). Aside from mild nuclear sclerosis in both eyes, the slit lamp and fundus exams were unremarkable. Notably, there was no chemosis or injection of the conjunctivae.

|

|

Fig. 1. Extraocular motilities in all gazes. Note periorbital fullness of the right side in primary gaze. There were adduction, abduction and supraduction limitations OD. Left eye motilities were full. Click image to enlarge. |

Differentials

At this point, the exam was concerning for an orbital process on the right side. Unilateral proptosis can be caused by several conditions. First, consider infectious and inflammatory causes. Orbital cellulitis is a painful infection of the content posterior to the orbital septum. It is most commonly associated with paranasal sinus infections. Orbital cellulitis may also be caused by trauma with or without retained foreign body, periocular surgery, preseptal cellulitis, dacryocystitis, dental infection or hematogenous spread.1 Prompt recognition and treatment is critical to prevent further spread of infection, which could ultimately lead to permanent vision loss or life-threatening complications.

Unilateral proptosis may also result from orbital inflammatory syndromes such as idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI). Typically, IOI is a painful, rapidly progressive condition that can be misdiagnosed as orbital cellulitis due to the overlap in clinical characteristics. Both disorders can present with significant conjunctival injection, pain, proptosis, vision loss and diplopia. A diagnosis of IOI is typically made only after an infectious entity and other inflammatory systemic conditions are ruled out.2

Thyroid eye disease (TED) should also be considered in patients who present with proptosis. Typically, TED presents with bilateral proptosis, diplopia, conjunctival injection and eyelid retraction. It may, however, present asymmetrically and appear as a unilateral process at the onset. If no prior history of thyroid dysfunction is known and the examination is suspicious for TED, patients should undergo a basic thyroid function panel. If negative, the provider should consider ordering thyroid auto-antibody titers. Our patient did not present with a history or clinical findings that would indicate an inflammatory orbital disorder or TED, so it was prudent to consider alternatives.

The next differential on our list was an orbital mass. These vary greatly in presentation, size and prognosis. Vascular lesions of the orbit such as lymphangiomas and cavernous venous malformations are benign but may still cause progressive proptosis, reduced vision and diplopia if they increase in size. Lymphoproliferative lesions are the most common orbital masses in older adults and include both lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma.3 Many cases of orbital lymphoma go undiagnosed for a period due to their slow growth. When these tumors do enlarge, they tend to conform around the globe and muscles, resulting in a less obvious mass effect. Orbital lymphoma generally lacks significant inflammation unless it is a more aggressive subtype, which can pose a diagnostic challenge.

|

|

Fig. 2. The “worm’s eye view” offers a better angle to evaluate the globes’ positions relative to one another, which can be helpful in unilateral globe displacement. Proptosis OD is evident relative to OS. Click image to enlarge. |

Next Steps

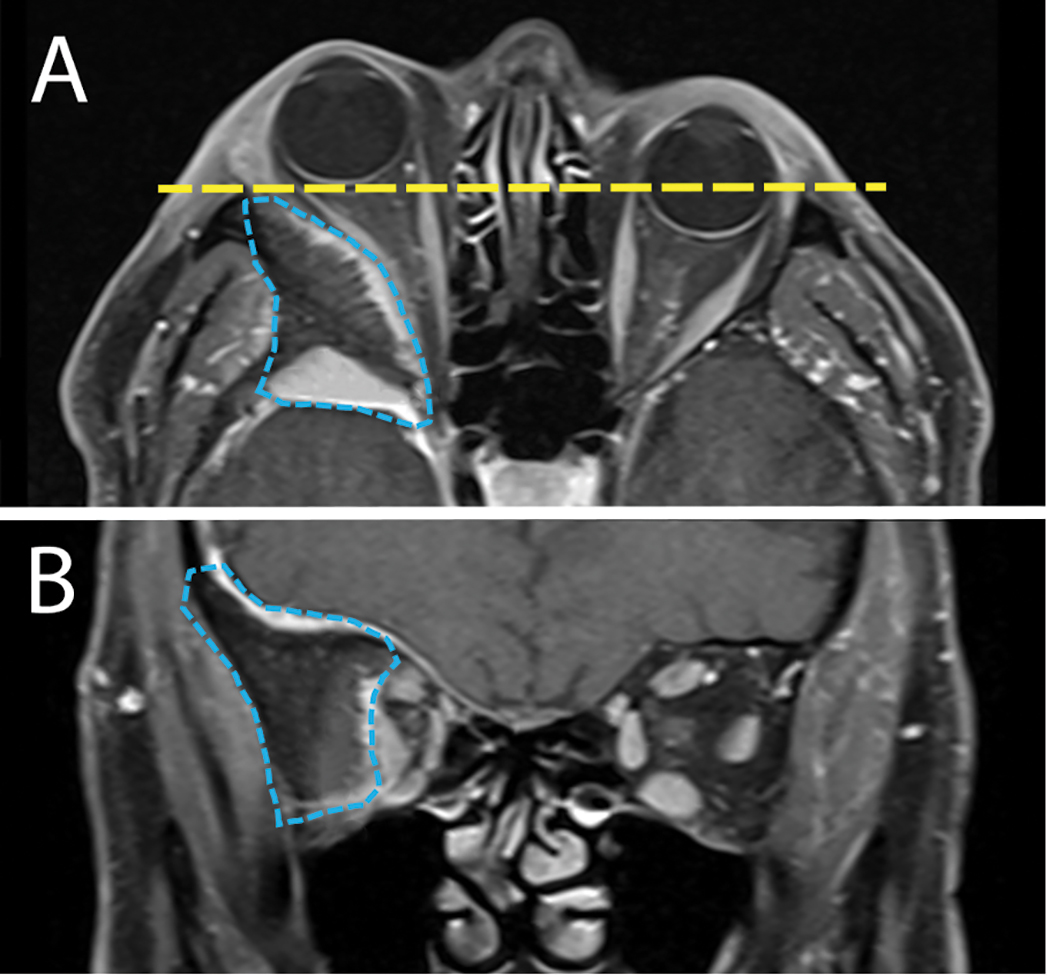

Based on the patient’s age and presenting features of unilateral proptosis, an APD, limited extraocular motilities and a lack of inflammation, the most likely diagnosis was an orbital neoplasm. MRI of the brain and orbit with and without contrast revealed an expansile mass arising from the right greater wing of the sphenoid bone that extended superiorly into the floor of both the anterior and middle cranial fossae. The lesion also expanded into the right lateral orbit. The intraorbital extension resulted in right-sided proptosis and crowding of the mid and apical orbit (Figure 3).

The lesion’s radiographic features, location and clinical history were most consistent with an intraosseous meningioma. The patient was referred to neurosurgery within two weeks, and a combined case was coordinated with an oculoplastics surgeon. The tumor was resected in full via a cranio-orbital approach, and pathology confirmed it to be WHO grade I meningioma.

At his two-month post-surgical follow-up, the patient reported significant improvement in his vision and headaches. He complained of facial numbness, diplopia and jaw pain with mastication but noted these symptoms were continually improving.

|

|

Fig. 3. A: Axial MRI orbit study reveals a large intraosseous lesion of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone (blue line). The mass resulted in right globe proptosis (yellow line). B: Coronal MRI view reveals the extensive bony lesion (blue line) causing significant orbital volume loss and medialization of all orbital content. Click image to enlarge. |

A Rare Subtype

Meningiomas are tumors that originate from the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord. They are the most common intracranial tumor and may be found incidentally on imaging.4 They grow slowly, so the onset of symptoms is often insidious. Though most meningiomas are benign, they can lead to headaches, seizures and focal neurologic deficits depending on their location and growth. Grade I are the most common (81.1%) and have the best prognosis. Grade II are less common, and grade III are the rarest (1.7%).5 As the grade increases, so does the likelihood of recurrence and complications.

Primary intraosseous meningiomas comprise 1% to 2% of all meningiomas.6 They form within the bones of the skull and are thought to arise from arachnoid cells trapped within the bone. Similar to other intracranial meningiomas, symptoms can vary and are mostly related to the tumor’s location. Calvarium lesions typically do not present with symptoms but may be noted as a hard scalp mass. Intraosseous meningiomas of the skull base, like in this patient, are more likely to lead to cranial neuropathies, vision changes or hearing loss due to their proximity to the brainstem and cavernous sinus.6

Total surgical resection of the intraosseous meningioma with wide margins is the treatment of choice when possible. Some tumors, particularly those involving the skull base, may not be amenable to total resection due to their location. Instead, these tumors may be partially removed to decompress neural structures. Though there is not significant data on outcomes with adjuvant therapies, some suggest radiotherapy to treat residual or recurrent tumors.7 Regardless of the treatment strategy, long-term radiologic follow-up is critical to monitor for recurrence or growth.8

Takeaways

This case highlights the importance of a thorough clinical examination when sorting out a patient’s symptoms. Given this patient’s relatively symmetric visual acuity and color vision, it is tempting to dismiss the chief complaint of blurred vision. However, the pupil exam and a subjective brightness assessment reinforced the importance of this symptom. The patient also did not notice diplopia until testing was completed in the exam lane with prism bars. A careful assessment of motilities and proptosis prompted neuroimaging, ultimately leading to a rare diagnosis and successful management.

Dr. Bozung works in the Ophthalmic Emergency Department of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (BPEI) in Miami and serves as the clinical site director of the Optometric Student Externship Program as well as the associate director of the Optometric Residence Program at BPEI. She has no financial interests to disclose.

|

1. Tsirouki T, Dastiridou AI, Flores NI, et al. Orbital cellulitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018;63(4):534-53. 2. Mombaerts I, Bilyk JR, Rose GE, et al. Consensus on diagnostic criteria of idiopathic orbital inflammation using a modified Delphi approach. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(7):769-76. 3. Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Orbital tumors in the older adult population. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(2):243-8. 4. Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, et al. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol. 2018;14(21):2161-77. 5. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Xu J, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009-2013. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(suppl 5):v1-75. 6. Chen TC. Primary intraosseous meningioma. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2016;27(2):189-93. 7. Crawford TS, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Lillehei KO. Primary intraosseous meningioma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(5):912-5. 8. Tokgoz N, Oner YA, Kaymaz M, et al. Primary intraosseous meningioma: CT and MRI appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(8):2053-6. |