Her ocular history was significant for myopia. She reported seeing well with daily disposable contact lenses. Her medical history was unremarkable.

Her best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/20 OU at distance and near with a small myopic correction. Ocular motility testing was normal OU. Confrontation visual fields were full to careful finger counting. Her pupils were equally round and reactive, with no evidence of afferent defect.

The anterior segment examination revealed a clear cornea with a deep and quiet chamber OU. Additionally, she exhibited normal irides and clear lenses.

Dilated fundus exam showed a clear vitreous. Both optic nerves were healthy, with small cups and good rim coloration and perfusion. The maculae appeared normal with a positive foveal light reflex OU.

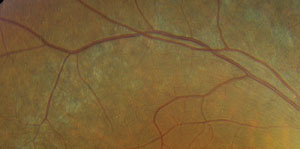

However, located just outside each macula, we saw peculiar retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) changes that extended along the superior and inferior arcades OU. We took wide-field fundus images of both eyes (figures 1 and 2), as well as captured a magnified view along the superior arcade OD (figure 3).

|

|

1, 2. Our patient’s fundus evaluation revealed obvious changes in both eyes (OD left, OS right). What is the correct diagnosis?

|

|

| 3. A magnified view along the right superior temporal arcade. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. How would you classify the fundus changes in our patient?

a. Degenerative.

b. Tapetoretinal.

c. Infectious.

d. Metabolic.

2. What do the small focal changes seen on the magnified fundus view represent?

a. Drusen.

b. Crystals.

c. Calcium.

d. Lipofuscin.

3. What is the correct diagnosis?

a. Retinitis pigmentosa.

b. Stargardt disease.

c. Cone dystrophy.

d. Bietti crystalline dystrophy (BCD).

4. Which principal symptom should we expect our patient to report?

a. Loss of color vision.

b. Night blindness.

c. Loss of central vision.

d. Blurred vision.

5. What testing would help us best follow this patient?

a. Fluorescein angiography.

b. Visual fields.

c. Electroretinogram (ERG).

d. Both b and c.

Discussion

The fundus changes seen in our patient are characteristic of a tapetoretinal degeneration––a collective term used to define a nonspecific, hereditary degeneration of the RPE and photoreceptors. Considering that there are several different hereditary retinal degenerations, which one does our patient have?

One clue can be spotted along the superior and inferior arcade where, upon close inspection, you can observe multiple, fine, refractile retinal crystals. Given these findings, we diagnosed our patient with a rare autosomal recessive condition––Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Patients with BCD typically exhibit crystals in the corneal limbus, glistening intraretinal crystals in the presence of RPE atrophy, pigment clumping and choroidal sclerosis.1

Interestingly, our patient didn’t have corneal crystals. Nonetheless, there are several published reports of BCD patients who presented with the typical retinal findings, but no evidence corneal crystals.1,2

Most patients who are diagnosed with BCD develop visual symptoms by the third decade of life. The disease usually progresses very slowly; however, the exact rate can vary based upon the individual’s genetic construct. The most commonly reported symptoms are decreased visual acuity and pronounced night blindness (nyctalopia).

The natural history of BCD includes progressive vision loss and visual field constriction. It is important to note that advanced age is not always a marker for disease severity and/or progression risk.1 Therefore, it is reasonable to suggest that environmental factors (e.g., dietary intake) may affect lipid metabolism, or that certain genetic variables might influence phenotypic disease expression.1,3

The gene for BCD has been localized to chromosome 4q35. Affected individuals often present with several different mutations of CYP4V2––a member of the cytochrome P450 family, which codes for a 525 amino acid protein.1 The CYP4V2 gene may play an active role in fatty acid metabolism and has been found in various ocular tissues, such as the retina and RPE.

Biochemical studies have shown that patients with BCD typically experience abnormal lipid metabolism.1 In one investigational study, BCD patients demonstrated a reduced capacity to convert fatty acid precursors into omega-3 fatty acids and were found to have absent or nonfunctional fatty acid binding proteins.2

Our patient was relatively asymptomatic, and still had 20/20 acuity. And while she reported some difficulty seeing at night, she suggested that it did not affect her ability to function properly.

BCD patients should be followed via visual fields and ERG studies. In fact, the clinical grading for BCD has been directly correlated to ERG findings.1 Patients with RPE atrophy and intraretinal crystals that are confined to the posterior pole tend to show lesser disturbances in the full-field ERG. Indeed, upon testing, our patient had an amplitude reduction in rod (within 20% of the low end of normal), mixed rod/cone (less than 30% of the low end of normal) and cone (between 40% and 50% of the low end of normal) function. Further, visual fields showed very slow progression over a six-year period, with slight constriction superiorly (OD > OS).

Our patient has done very well with this condition. She maintains excellent visual acuity, and is not aware of any associated difficulties. In fact, she wouldn’t have even known that she had a problem if it weren’t for her myopia.

Retina Quiz Answers: 1) b; 2) b; 3) d; 4) b; 5) d.

1. Lee KY, Kob AH, Aung T, et al. Characterization of Bietti crystalline dystrophy patients with CYP4V2 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005 Oct;46(10):3812-6.

2. Mataftsi A. Bietti’s crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy: a cross-sectional study. Retina. 2004 Jun;24(3):416-26.

3. Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Chan CC, Markello TC, et al. Clinical biochemical and pathologic correlations in Bietti’s crystalline dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994 Nov 15;118(5):569-82.