13th Annual Pharmaceuticals ReportCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: Steroid Wars: New Drugs Challenge Old Habits |

As optometrists, we are well positioned to diagnose and treat glaucoma; however, it’s not as simple as identifying someone with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and then lowering it as much as possible. One report from nearly 20 years ago calculated more than 56,000 ways to treat glaucoma after taking into account all available medications and possible regimens ranging from monotherapy to maximum medical therapy.1 With new treatments at our disposal, that number is now considerably higher.

In addition, glaucoma itself is a complex condition with varying presentations, rates of progression and responses to treatment. Properly treating the condition first requires the clinician to accurately identify the type of glaucoma, order and analyze appropriate testing and initiate an appropriate treatment plan with suitable follow up—there is no one-size-fits-all treatment protocol.

Although glaucoma care remains more of an art than an exact science, a structured approach allows us to initiate—and tweak—treatment plans for each individual.

Where You Start Matters

The diagnosis and decision to initiate treatment is based on a comprehensive glaucoma workup that includes a detailed case history, slit lamp biomicroscopy, tonometry, pachymetry, gonioscopy, retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell complex imaging, perimetry and dilated optic nerve assessment. One of the most challenging aspects of managing glaucoma is the interpretation of this conglomeration of data.

The dilated fundus exam, with an assessment of the optic nerve head, is one of the most important parts of a glaucoma evaluation. Pay close attention to the cup-to-disc ratio, integrity of the neuroretinal rim and the presence or absence of an optic disc hemorrhage, peripapillary changes and baring or bayoneting of the retinal vasculature. Indications of glaucomatous changes noted during a dilated fundus exam should correlate and be consistent with optical coherence tomography (OCT) and visual field findings to warrant initiation of treatment. Beyond using gonioscopy for the initial diagnosis and classification of glaucoma, this testing should be repeated annually, as the anterior chamber angle tends to narrow with age. When determining whether to initiate treatment, pachymetry values and corneal hysteresis are especially important, as patients with thin corneas and low corneal hysteresis values are at an increased risk of developing glaucoma.2

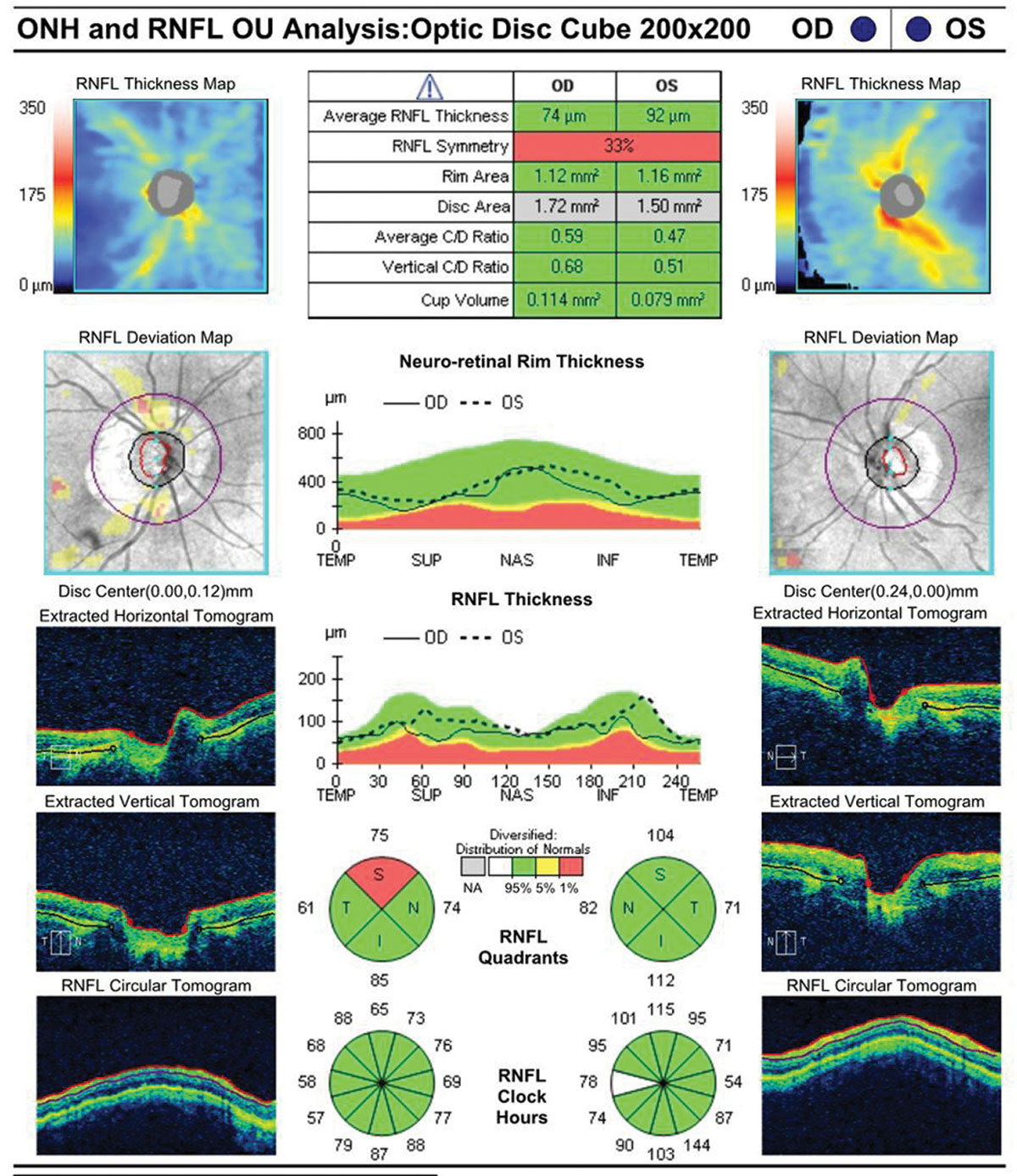

| Fig. 1. This 92-year-old white female is currently taking latanoprost OU at bedtime. She has a maximum IOP of 22mm Hg with an IOP on exam of 18mm Hg OU. Corneal thicknesses are 523µm OD and 520µm OS. The patient’s testing shows only mild visual field loss. Given her age and clinical picture, it is unlikely she will experience real functional impairment in her lifetime. A mild (even if confirmed) progression of RNFL loss might not be an indication to escalate therapy. Click images to enlarge. |  |

| |

First-line Options

The decision to initiate treatment—and what treatment to start with—should take into account testing, exam findings, the individual’s risk factors for developing glaucoma, the burden of long-term treatment, possible adverse effects, inconvenience and cost.3 Initial therapy with drops or selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) are both acceptable first-line treatments.

Prostaglandin analogs have been the preferred initial pharmaceutical treatment due to their ability to effectively lower IOP with a once-daily dose.4 Research shows prostaglandin analogs are superior to other topical IOP-lowering classes in controlling diurnal and nocturnal IOP.4 Prostaglandins are also extremely safe, with no reported systemic adverse reactions.5 However, ocular side effects include darkening of iris color, lash growth, periocular skin pigmentation, fat distribution changes and conjunctival hyperemia.4,5 These ocular side effects should be considered, especially when treating unilaterally or in younger patients.

SLT is also a viable first-line treatment option. Recently, the Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension Study demonstrated that SLT is both clinically effective and cost-effective as an initial intervention for primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and ocular hypertension.6 The benefits of SLT include eliminating the risk of poor compliance with medications, given the burdens placed on patients who must take one or more topical hypotensive agents daily.

Change Tactics

After initiating therapy, follow-up is guided by the severity of disease. Typically, monitoring patients with serial OCT and visual fields every six to 12 months for mild disease and every six months for moderate to severe disease is sufficient.

The concept of reaching a target IOP has gained acceptance in glaucoma management; however, it remains unclear whether that target number should be a percent reduction, an absolute number, low IOP fluctuations or low nocturnal IOP.7 This treatment approach was reinforced by a post hoc analysis from the Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study, which suggested that lowering IOP to below 18mm Hg at all visits or an average IOP of 12.3mm Hg would halt glaucoma progression.4 Other landmark glaucoma studies provide evidence for percent reduction in IOP.

Still, practitioners who rigidly adhere to a target level or range may potentially be doing more harm than good, especially in low-risk patients with thick corneas.4 The target IOP concept is also limited by the fact that glaucoma care involves balancing the complex set of risks and benefits that accompany escalating therapy. Simply adding medications to reach a target IOP, regardless of evidence of disease progression, does not take these considerations into account. Lastly, no randomized clinical control trials show that the use of a target IOP is superior to any other approach.4

Instead, clinicians should take into account both structural and functional changes as well as potential adverse reactions, costs to the patient and burden of treatment prior to escalating medical treatment or considering surgical intervention. An experienced clinician takes a dynamic approach, weighing these risks and benefits, with an understanding that these factors change over time. Thus, treatment decisions should be made based on the current disease state of an individual patient and their progression.4

Glaucoma FAQsGlaucoma is the leading cause of blindness in the United States, and researchers estimate that three to six million people are at risk of developing the condition because of elevated IOP.1 Furthermore, large epidemiologic studies show that one third to approximately half of glaucoma cases have an IOP at or below 21mm Hg.2 Other population-based studies show that only 50% of patients with glaucomatous visual field loss have received an appropriate diagnosis or treatment and that 50% of glaucoma cases may be undiagnosed.2,3 Within the United States, therapeutic management of glaucoma costs an estimated $2.5 billion annually.4 With these numbers in mind, not only is early detection and treatment important for preserving a patient’s vision and quality of life, it is also important to treat the patient appropriately and avoid over-treatment. Classification of glaucoma is important to ensure proper treatment paradigms. By definition, glaucoma is a diverse group of conditions that potentially results in progressive damage to the RNFL and associated visual field loss as the disease progresses.3 Clinically, glaucoma is managed by lowering the patient’s IOP because landmark glaucoma treatment trials demonstrate that reduction in IOP is associated with a reduced risk of visual field progression.5 The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study helped identify key risk factors for glaucoma patients. It also showed that topical hypotensive therapy is effective in reducing the incidence of glaucoma in ocular hypertensive patients. The study demonstrated that delaying treatment has a small effect on the incidence of POAG in low-risk patients but has a larger effect on reducing the incidence of glaucoma in high-risk patients.1,3 In the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial, each 1mm Hg increase in IOP during follow up was associated with a 12% increase in the development of visual field progression.2 Understanding the fundamental elements of these studies and incorporating their clinical pearls is critically important in the management of glaucoma.

|

OCT and visual field testing play a critical role in evaluating structural and functional changes and monitoring for disease progression. Although white-on-white perimetry has been considered the standard for monitoring glaucoma, progressive RNFL thinning increases the risk of visual field progression, and a significant amount of RNFL damage can occur before a functional defect is apparent on visual field testing.8,9 OCT analysis provides an objective measure of the RNFL thickness.8 Repeatable evidence of RNFL thinning on OCT or repeatable visual field progression are indications to consider changing a patient’s glaucoma treatment. Recent studies show that loss of the ganglion cell complex may occur prior to loss of the RNFL, and assessment of the ganglion cell complex may be useful in determining progression of patients with pre-perimetric glaucoma.9

For example, if a patient’s IOP and visual fields are stable but progressive RNFL thinning is confirmed on repeat testing, this would be an indication to consider escalating the patient’s treatment. However, if a patient has borderline IOP control and stable RNFL and visual fields, this would be an indication to monitor without changing the treatment regimen. When evaluating testing and making the decision to escalate or initiate therapy, the patient’s age, life expectancy and stage of glaucoma must also be taken into account (Figure 1).

Once a patient’s clinical picture dictates a change in their glaucoma management, clinicians should remember to make one change at a time. Using a single medication as an adjunct therapy prior to moving to a combination drop allows the practitioner to assess if the patient has an adequate IOP reduction with the new medication. It also allows the practitioner to assess the patient’s tolerance of the new adjunct therapy. If the IOP response is inadequate with the initial adjunct therapy or the patient exhibits progression, you still have the option to change the treatment by either recommending SLT or switching the patient to a combination drop.

Many clinicians turn to beta blockers as a first-line adjunct medication for patients already on a prostaglandin analog. This class of medication is typically well tolerated and can be dosed once or twice a day.4 Beta blockers are contraindicated in patients with asthma, bronchospasm, chronic obstructive lung disease, heart failure, sinus bradycardia, atrioventricular block and cardiogenic shock.5 A second option for adjunct therapy is a topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, which has better control of diurnal IOP fluctuations when used as an adjunct treatment with a prostaglandin analog.4

In patients for whom a beta blocker is contraindicated or who do not have an adequate response to a beta blocker, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, alpha 2-agonist or the rho-kinase inhibitor netarsudil (Rhopressa, Aerie Pharmaceuticals) are viable next options for increasing the patient’s treatment.

Additional Considerations

Before altering a patient’s glaucoma treatment, clinicians should also consider cost, brand name vs. generic and adverse reactions to medication.

Financial burden. Glaucoma medications can be expensive, and the yearly cost of a medication can vary greatly depending on the class, whether it is branded or generic and dosing frequency.10 Clinicians should consider the patient’s formulary, the efficacy of the medication and patient financial obligations while treating glaucoma.

Branded vs. generic. Most commonly, clinicians switch to a generic medication due to cost. While generic medications must contain the same concentration of active ingredients, they often vary in non-active ingredients, bottle design and drop volume.11 Therapeutic dosage in a topical medication is largely dependent on drop volume, and the potential for smaller drop volume in generic medications means patients could receive less of the active ingredient per instillation, potentially resulting in a lower daily prescribed dose.11 This lack of dose consistency can be concerning for the long-term management of glaucoma patients.

Generic medications also have different names and come in different packages, which can be confusing for patients, especially for those with low health care literacy.11 Such patients have poor compliance with glaucoma treatment and worse visual field results on follow up examination.12 Thus, for certain patients the variability in generic medications may compound with existing confusion from a multi-drop regimen, resulting in worse compliance. In these cases, the consistency of a brand-name medication, despite cost issues, may be valuable in potentially improving compliance and ultimately effectiveness of treatment.

Adverse reactions. One of the main goals of glaucoma treatment is to maximize the IOP-lowering effect while limiting adverse reactions. Most preservatives act as surfactants, which destabilize bacterial cell membranes and result in the destruction of the cell membrane, inhibition of cell growth and reduction of cell adhesiveness. Preservatives also exert this effect on corneal and conjunctival cells. This may result in ocular surface disorders, including superficial punctate keratitis, corneal erosion, conjunctival allergy, conjunctival injection and anterior chamber reaction.5 Patients who are exhibiting a toxic reaction to a medication or cannot tolerate the medication could benefit from a preservative-free version.

Another common ocular adverse reaction in glaucoma patients is follicular conjunctivitis secondary to an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist such as brimonidine.5 If the patient exhibits a follicular response, hyperemia or simply does not tolerate this class of medication, an alternative class is indicated. Additionally, for patients with more severe glaucoma or who may require surgical intervention with filtration surgery, consider avoiding alpha-2 agonists, as they can decrease conjunctival mobility and make filtration surgeries more difficult secondary to the chronic follicular conjunctivitis.

|

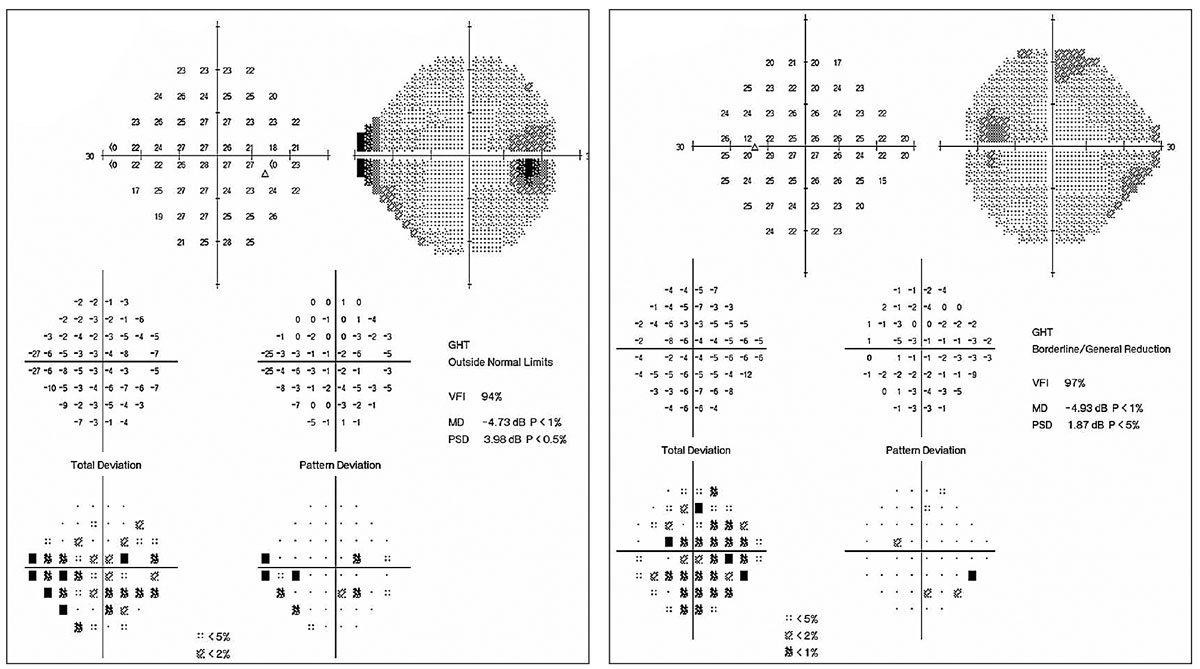

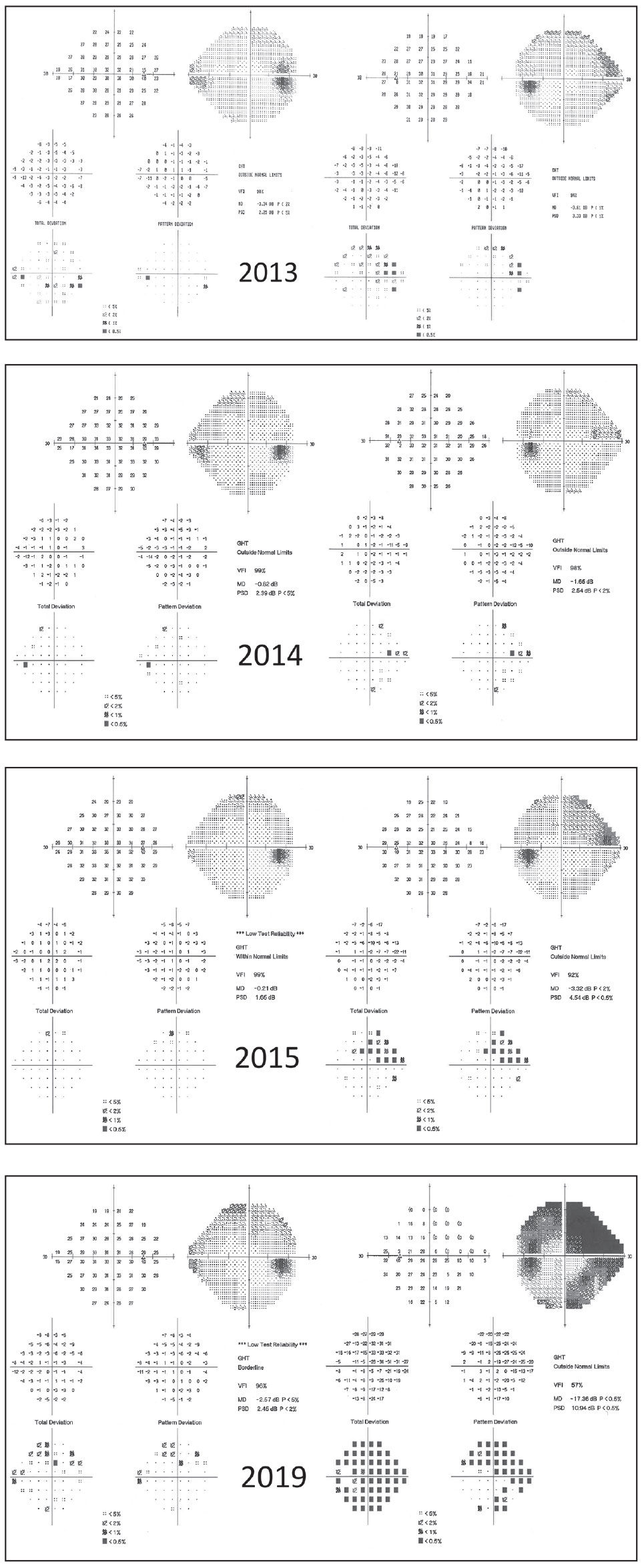

| Fig. 2. This 59-year-old male was lost to follow up for four years, during which time he discontinued his drops. His visual fields demonstrate progression. Patients such as this might benefit from surgical intervention rather than topical therapy. Click image to enlarge. |

New Horizons

For the first time in more than 20 years we now have two new classes of glaucoma medications available to us. Vyzulta (latanoprostene bunod 0.024%, Bausch + Lomb) is metabolized into latanoprost and donates nitric oxide once the medication is in the eye—targeting both uveoscleral and trabecular outflow.12 Research shows Vyzulta has a safe systemic profile, with the most common reported ocular side effect being hyperemia.12 The medication has also demonstrated a robust IOP-lowering effect of 9mm Hg.13 This considerable effect suggests Vyzulta could potentially be used as first-line therapy.

The other new class of topical IOP-lowering medication is the aforementioned Rhopressa, a rho-kinase inhibitor that acts to increase trabecular outflow.12 This drug class has a safe systemic profile but comes with two unique ocular side effects: small conjunctival hemorrhages and corneal verticillata.13 These side effects usually resolve upon discontinuing the medication and typically do not have any impact on the patient’s vision. Rhopressa had an IOP-lowering effect similar to that of timolol, and research shows it’s non-inferior to timolol, making it a suitable first- or second-line adjunct therapy.12

Rocklatan (netarsudil 0.02%/latanoprost 0.005% ophthalmic solution, Aerie) is another new topical glaucoma therapy. Clinical trials demonstrate that the fixed combination is more effective at lowering IOP than either medication alone. The once-daily dosing and demonstrated success in lowering IOP suggest that Rocklatan may be a good first-line therapy or a beneficial medication to consider in patients with complex dosing regiments.14 The same risk/benefit considerations should be given when prescribing these medications as to other topical glaucoma medications.

Surgical Intervention

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) are generally ab interno, micro-incisional, conjunctiva-sparing procedures that prioritize patient safety and have a demonstrated efficacy in lowering IOP.15 MIGS offer a less-invasive option for lowering IOP than other traditional filtering and shunt surgeries.

These devices fall into three main implant categories: (1) increase trabecular outflow by bypassing the juxtacanalicular trabecular meshwork, (2) increase uveoscleral outflow via suprachoroidal pathways or (3) create a subconjunctival drainage pathway.15 Research shows MIGS can provide IOP control in the mid to low teens while reducing the need for topical hypotensive agents.15 Optometrists should consider referring patients with mild to moderate POAG and cataracts to surgeons who are performing MIGS procedures.

Clinicians should also consider consultation for surgical intervention in patients who are progressing despite topical therapy with two or three medications, have fixation-threatening visual fields, cannot tolerate topical medications secondary to ocular or systemic side effects and for whom the use of regular topical therapy is not realistic secondary to their social situation or comorbid conditions (Figure 2).16

Glaucoma management requires a dynamic approach that carefully weighs the risks and benefits of a particular therapy. Each patient’s status will likely change over time, requiring treatment adjustments along the way. A careful assessment of both structural and functional changes as well as potential adverse reactions, costs and the burden of treatment can help you determine when, and how, to escalate treatment.

There is no one-size-fits-all treatment regimen for glaucoma. Rather, changing a patient’s glaucoma therapy is a complex art involving careful thought and consideration of the patient’s glaucoma status, response to treatment, indicators of progression, medication cost, adverse reactions and the patient’s quality of life.

Dr. Mackner completed his residency in ocular disease and surgical comanagement at Omni Eye Services in New York and New Jersey. He currently practices at Edina Eye Physicians and Surgeons in Minnesota.

1. Realini T, Fechtner RD. 56,000 ways to treat glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(11):1955-56. 2. Kanski JJ, Bowling B. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. 3. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701-13. 4. Singh K, Shrivastava A. Medical management of glaucoma: principles and practice. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(Suppl1):S88. 5. Inoue K. Managing adverse effects of glaucoma medications. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:903-13. 6. Tsai C, Sng C, Barton K. Light on the horizon: evidence from randomized controlled trials supports the use of two less invasive glaucoma treatment options, selective laser trabeculoplasty and a microstent. Glaucoma Today. 2019;18-20. 7. Radcliffe N. Changing treatment paradigms in glaucoma. Rev Ophthalmol. 2012;19(11):58. 8. Leung C. Monitoring glaucoma progression with OCT detection of progressive RNFL thinning with GPA/TPA aids in management & treatment decisions. Ophthalmol Manage. 2017;21:16-18. 9. Bhagat PR, Deshpande KV, Natu B. Utility of ganglion cell complex analysis in early diagnosis and monitoring of glaucoma using a different spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2014;8(3):101-106. 10. Rylander NR, Vold SD. Cost analysis of glaucoma medications. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(1):106-13. 11. Mammo ZN, Flanagan JG, James DF, Trope GE. Generic versus brand-name North American topical glaucoma drops. Canadian J Ophthalmol. 2012;47(1):55-61. 12. Juzych MS, Randhawa S, Shukairy A, et al. Functional health literacy in patients with glaucoma in urban settings. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(5):718-24. 13. Khouri A. Two unique glaucoma drugs debut. Rev Ophthalmol. 2018;25(6):56-59. 14. Sinha S, Lee D, Kolomeyer NN, et al. Fixed combination netarsudil-latanoprost for the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Exp Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(1):39-45. 15. Ansari E. An update on implants for minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS). Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6(2):233-41. 16. Dietlein TS, Hermann MM, Jordan JF. The medical and surgical treatment of glaucoma. Deutsches Aerzteblatt International. 2009;106(37):597. |