A 77-year-old white male with primary open-angle glaucoma and atrophic macular degeneration presented for an IOP check and dilated fundus exam O.U.

The patient has a one-year history of open-angle glaucoma and atrophic macular degeneration for which he took Xalatan (latano-prost, Pfizer) 1 drop O.U. daily at bedtime and ICAPS (Alcon), respectively. He also took vitamin E 400IU and vitamin C 500mg. The patient had no visual complaints and reported good compliance with his glaucoma medication. Some five to seven years ago, the patient underwent cataract extraction and YAG capsulotomy in both eyes without complications.

The patients medical history was significant for type-2 diabetes mellitus for 34 years, hypertension, coronary artery bypass graft, hyperkalemia (abnormally high potassium), urolithiasis (urinary calculi), chronic ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, renal failure and mixed hyperlipidemia. Though the patient was a smoker, he had no significant breathing problems. He took several medications to manage systemic disorders.

Diagnostic Data

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25 O.D. and 20/30 O.S. Extra-ocular muscles and confrontation fields were unremarkable. Pupils were reactive with no afferent pupillary defect. Refraction showed presbyopia with negligible changes to current spectacle prescription.

Anterior segment exam revealed pseudophakia with open posterior capsules in both eyes. Also, moderate dermatochalasis in both eyes produced a mild mechanical ptosis that was greater in the right eye than the left. Intraocular pressure measured 15mm Hg O.D. and 16mm Hg O.S.

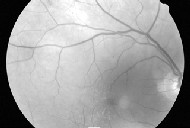

A central, pigmented spot with an annulus of retinal pigmentary thinning.

Dilated fundus examination revealed vitreous syneresis O.U. with significant asteroid hyalosis O.S. The optic nerves demonstrated moderate cupping with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.6 x 0.6 O.U.

Indirect biomicroscopy of each macula revealed medium-sized soft drusen centrally. There was mottling of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and trace scattered microaneurysms were present throughout the arcades. There was no clinically significant macular edema in either eye.

We also noted a slightly elevated subretinal lesion with a gray-greenish center located just nasal to the foveal avascular zone O.D. It was cream-colored and approximately 0.33DD. We observed no associated hemorrhages or exudates.

Diagnosis

We diagnosed this patient with mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy and well-controlled primary open-angle glaucoma, and tentatively diagnosed a juxtafoveal choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) secondary to macular degeneration in the right eye.

Treatment and Follow-up

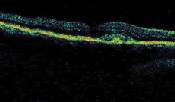

We referred the patient to a retinal specialist for immediate evaluation of the macula and to rule out the need for surgical intervention. The next day, the retinologist performed optical coherence tomography, which showed a subtle area of retinal elevation over a dome of retinal pigment epithelial thickening.

The retinal specialist also noted a 600m to 700m area of discolored RPE that consisted of a central pigmented spot with an annulus of retinal pigmentary thinning, surrounded by a zone of less impressive hyperpigmentation.

Red-free photography shows a cream colored lesion without visible pigment.

The retinal specialist diagnosed adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy (AOFVD). The lesion lacked evidence of subretinal hemorrhage or fluid. It had a pigmented center rather than the pigmented periphery that would be seen with CNVM.

We instructed the patient to monitor his central vision at home with an Amsler grid and to continue taking his vitamin supplements. We scheduled a follow-up visit for three months.

Discussion

AOFVD typically presents as a subretinal deposit of yellowish material that is circular, elevated and localized in the macular area. It often has at its center a pigmented spot that corresponds to a clump of large pigment cells and extracellular pigment thought to be in combination with lipofuscin.1,2 Lipofuscin is a yellowish-brown metabolic by-product that accumulates in the RPE with age. While reports typically agree that the AOFVD deposits lie in the area between the neural retina and Bruchs membrane, the exact location of the deposit may be within the RPE, or anterior or posterior to the RPE.3,4

Onset of AOFVD typically occurs between ages 40 and 70, with mild to moderate symptoms, and normal or subnormal electro-oculogram.5 Autosomal dominant inheritance with variable penetrance is suspected.5

In the long term, AOFVD can lead to the clinical appearance of geographic macular atrophy due to loss of the RPE and choriocapillaris. This can result in varying degrees of vision loss, similar to age-related macular degeneration.5 The greater the mass of the lesion, the more the retinal contour and photoreceptors are altered, resulting in metamorphopsia. Lesions direct-ly underlying the foveal pit will be the most symptomatic.

OCT allows us to observe the retina in vivo. The OCT of AOFVD typically shows a well-defined subretinal thickening in a reflective band. This represents an elevation of the RPE above a moderately reflective region with a defined posterior boundary. The overlying neurosensory retina is elevated, and may exhibit compression and secondary thinning of the photoreceptor layer.6

The RPE layer appears highly reflective on OCT, due to the high melanin concentration. Typically it becomes less reflective under the pseudovitelliform material, most likely due to dampening of the signal by the pseudovitelliform lesion. In some cases, however, the difference between RPE and the pseudovitelliform lesion may be difficult to discern by standard OCT. A second OCT exam in which the noise and range functions are altered to filter background noise may help differentiate the RPE and pseudo-vitelliform lesion due to a slightly lower reflectivity.4

Subtle area of retinal elevation over a dome of retinal pigment epithelial thickening.

Red-free photographs reveal AOFVD lesions as round and whit-ish in color. In the majority of cases of AOFVD, fluorescein angiography shows a central hypofluorescent spot surrounded by an irregular hyperfluorescent ring.1 The hyp-erfluorescent area is the direct result of circumferential thinning of the RPE around the edges of the lesion.

Late-phase hyperfluorescence can mimic a CNVM. Pay close attention to the size of the hyperfluorescent zone during the early stages of the angiogram to differentiate this staining pattern from that of a CNVM.5 Intensity of the staining may increase, but the size and shape should remain constant.5

Reports in the literature document the difficulties of differentiating a diagnosis of AOFVD vs. CNVM.3 In some cases, misdiagnosis was not realized until after the patient underwent photodynamic therapy (PDT). Fortunately, PDT done in the setting of no CNVM and no subretinal fluid does not seem to cause any significant ad-verse effects.3 Nevertheless it is not an effective treatment for AOFVD.

Differential diagnosis includes:

Bests vitelliform dystrophy. Patients with Bests disease typically present with a large, yellow, yolk-like lesion that is located bilaterally in the central macula. This type of lesion is often visible before age 20, but patients may remain asymptomatic for years. Visual acuity often remains good as long as the lesion is intact. Once scarring begins, vision drops.

Exudative macular degeneration. Signs associated with exudative AMD include subretinal hemorrhages, elevation of the RPE, edema in the sensory retina, subretinal exudates, subretinal pigment ring, disciform scarring, and retinal or vitreous hemorrhage.7 Subtle cases may present with only subretinal fluid.

A CNVM becomes apparent as new blood vessels grow through breaks in Bruchs membrane allowing entry into the sub-RPE space from the choriocapillaris. The newly constructed vessels alter the structure of the RPE and may begin to leak, causing tissue destruction.

Other differential diagnoses of AOFVD include RPE detachment, toxoplasmosis and RPE dystrophies like central serous chorioretinopathy.4

There is currently no treatment for AOFVD. Monitoring is the only option in the absence of subretinal hemorrhage or fluid. We must closely monitor patients with moderate to severe atrophic macular degeneration for the development of CNVM. A CNVM can cause permanent and significant visual disability. Urgent evaluation and treatment are essential.

AOVFD is a subretinal entity with subtle characteristics that differentiate from the gray-green lesion associated with CNVM. Given its propensity to fool the experts, prompt referral to a retinal specialist is necessary.

This case underscores the complexity in the diagnosis of CNVM, and demonstrates the value of modern diagnostic testing to aid in diagnosis and management.

Dr. Maier is on staff at the Spokane Eye Clinic in Spokane, Wash. Dr. Riley is chief of optometry and residency director at the Spokane VA Medical Center.

1. Pierro L, Tremolada G, Introini U, et al. optical coherence tomography findings in adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 2002 Nov;134(5):675-80.

2. Yamaguchi K, Yoshida M, Kano T, et al. Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy with retinal folds. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2001 Sep-Oct;45(5):533-7.

3. Menchini U, Giacomelli G, Cappelli S, et al. Photodynamic therapy in adult-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy misdiagnosed as choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Dec;120(12):1761-3.

4. Benhamou N, Souied EH, Zolf R, et al. Adult-onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy: a study by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Mar;135(3):362-7.

5. Dufek MA, Penn S. Adult onset foveomacular vitelliform dystrophy: a case report. J Am Optom Assoc 1998 Aug;69(8):510-8.

6. Puliafito C, Hee M, Schuman J and Fujimoto J. Zeiss Humphrey Systems OCT2 Owners Manual. Zeiss Humphrey Systems, January 2002.

7. Rhee D, Pyfer M. The Wills Eye Manual-Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 3rd ed. Philadelphia :Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 1999: 350-2.