Bandage contact lenses (BCLs) are relatively low cost and can be used for a variety of therapeutic purposes. They heal injured corneal tissue and relieve pain and discomfort by protectively shielding the cornea from shearing forces of eyelids on blinking as well as from eye movements under the lids, thus preserving integrity of newly forming epithelial cell.1-7

BCLs also stimulate corneal metabolism, enhance corneal regeneration, increase epithelial adhesion, maintain hydration, reduce accumulation of collagenase, decrease edema and improve corneal transparency and vision.1,4,8 Future therapeutic considerations include the use of contact lenses as surgical adjuncts as well as vehicles for ophthalmic drug delivery.1,2,6

Background

In the last 150 years many therapeutic applications for contact lenses were considered, including using plastic polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) for treatment of conditions such as keratoconus.1,2,9 As newer materials have developed, including cellulose acetyl butyrate, siloxane methacrylates, silicones and hydrogels, therapeutic indications of bandage lenses evolved and gained wider appeal, with such lenses first being approved for therapeutic use in the 1970s.1,2,4-6,10

Development of silicone hydrogel (SiHy) has been critical for BCLs due to increased oxygen transmissibility and higher modulus, allowing for safer overnight wear with minimized corneal edema, improved mechanical protection and corneal healing, greater ease of handling and reduced hypoxia-related adverse events associated with extended CL wear.1,4-6,11

Currently, three SiHy lens materials of varying modulus are FDA approved for therapeutic use: lotrafilcon A, balafilcon A and senofilcon A. Lotrafilcon A and balafilcon A have stiffer moduli, which aids in lens handling, but also contribute to exacerbation of mechanical obstacles, including superior epithelial arcuate lesions and giant papillary conjunctivitis.11 Senofilcon A has a lower modulus and coefficient of friction, contributing to increased comfort and decreased potential for mechanical complications.11

|

|

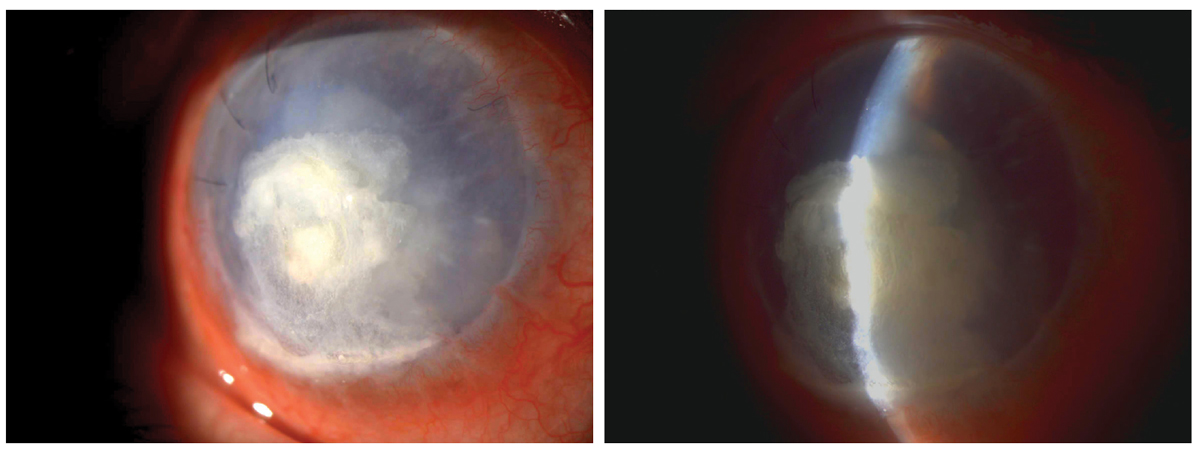

Bandage contact lenses are beneficial for corneal protection in this case of corneal perforation. Click image to enlarge. |

Common Uses

When the cornea needs protection from mechanical trauma during wound healing and a decrease in pain stimuli, BCL application can provide much-needed relief and respite.12-18

Corneal conditions that benefit from BCL therapy include abrasions, recurrent corneal erosions (RCE), post-surgical defects, bullous keratopathy, neurotrophic ulcers, dellen and dystrophies.13,14,19-21 Although abrasions do not always necessitate treatment, symptomatic relief and healing time can be facilitated with copious artificial tears/ocular lubricants, pressure patching and BCLs, particularly for larger defects.14-16,22

Contact lenses provide nearly instantaneous pain relief, as they protect exposed corneal nerves, preserve binocularity and cosmesis (unlike traditional pressure patches), improve visual acuity, can be combined with topical antibiotics for microbial prophylaxis and can be re-sterilized.6,15,19-21,23-25 Additional remedies, used alone or in combination, include topical steroids and metalloproteinase inhibitors, hypertonic solutions for corneal edema and oral doxycycline.14,19,24

Numerous clinical studies have described BCL therapy for corneal defects. The time necessary for return to normal activities has been shown to be significantly less in patients treated with BCLs vs. pressure patching and bandage lenses combined with topical NSAID use was found to be more comfortable than pressure patching or BCL wear alone.15 One study indicated a more rapid recovery in patients with corneal erosions treated with BCLs vs. control, in which the compromised eye was treated by covering.25 Furthermore, BCLs were found to lessen pain and decrease corneal erosion size to a greater extent than pressure patching.16

Another study, however, found no significant difference in pain relief and abrasion area between pressure patching, BCLs and ofloxacin ointment alone in the treatment of traumatic abrasions following corneal foreign body removal.24 One 1985 study demonstrated increased efficacy of ocular lubricants over BCLs for the treatment of RCEs; however, improved performance of BCLs seen in recent literature is likely due to newer lens materials with increased oxygen transmission that have since become available.18,26

One such study demonstrated a comparable percentage of patients achieving complete resolution of RCEs between subjects treated with ocular lubricants vs. BCLs; however, patients receiving BCL therapy achieved complete resolution at a faster rate and with better initial pain scores.18 In another study—of 12 patients with a history of RCEs that previously failed conservative treatment with ocular lubricants and nightly ointments—application of an extended-wear BCL in combination with topical ofloxacin produced long-term symptom relief and prevented signs of recurrences at one year or more of follow-up.17

Additionally, therapeutic BCLs have been indicated in children.27 One study of 29 pediatric eyes reported 93% efficacy of extended BCL wear in conditions including corneal burn, erosions, ulceration, perforation, neurotrophic keratopathy, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, herpetic keratitis, keratouveitis, descemetocele and exposure keratopathy.27 In one case, BCLs provided successful treatment of keratopathy secondary to lagophthalmos, thereby delaying more invasive tarsorrhaphy.27

Conventional hydrogel soft contact lenses have been documented extensively in the healing of epithelial defects and were often worn on an extended wear schedule in conjunction with ocular lubricants.14 With the advent of silicone hydrogel (SiHy), conventional hydrogels became outmoded for therapeutic purposes, as the oxygen transmissibility (Dk/t) of SiHy superseded that of conventional hydrogels.14,15

Post-Surgical BCLs

Soft bandage lenses are often used for wound coverage, such as placement after surgical procedures, including superficial keratectomy, phototherapeutic keratectomy and corneal collagen crosslinking.

Refractive surgery. Bandage contact lens application has been extensively noted in the postoperative management of photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), which typically results in ocular pain post-surgery due to corneal nerve damage and release of inflammatory factors.28-30 BCLs promote pain relief and speed re-epithelialization and may be used for three to five days post-PRK in concert with topical anesthetics, NSAIDs, artificial tears, oral analgesics and, in some cases, oral anticonvulsants.28-30 A multitude of studies have been conducted to determine the relative efficacy of various BCL materials and fitting parameters in speeding up recovery post-PRK.28,29,31-36 Materials have been shown to differentially impact re-epithelialization rate, epithelial defect size, pain, discomfort, foreign body sensation, epiphora and postoperative visual acuity.28,29,31-36 Regarding fitting parameters, most patients preferred steeper base curve lenses, with the exception of patients with flattest K values preferring larger base curve lenses.28,37

The use of BCLs has also been noted in the postoperative management of flap-based refractive procedures (LASIK/LASEK) for the promotion of corneal wound healing and epithelial regeneration, proper epithelial flap positioning, corneal protection and relief of pain and discomfort.38-40 In order to minimize edema and hypoxia associated with BCL wear, higher Dk SiHys are preferred to traditional hydrogels and are able to satisfy corneal oxygen requirements during extended and overnight wear.38-42 Furthermore, Dk plays a role in corneal epithelial repair and pain relief post-surgery. Several studies have explored the relative performance of various SiHy materials following flap-based procedures, demonstrating that varying materials differentially affect re-epithelialization rate, pain and epiphora.38,39

To maximize pain relief with BCLs, fit tighter lenses with smaller base curves that minimize lens movement on the eye (albeit, ensuring adequate movement, stability and centration), as well as fit lenses with higher water content.38,39 Concomitant therapy with topical antibiotics, anti-inflammatories and artificial tears is recommended.39

Visual acuity may be worse in the immediate postoperative period for patients managed with BCLs, which may be due to increased corneal flap edema associated with BCL wear.40,42 Furthermore, higher asymmetry in corneal radii may exist temporarily due to BCL-induced warpage and mucoid secretions are higher in patients treated with BCLs.40,42

Keratoplasty. Postoperative use of BCLs in patients that have recently undergone a full- or partial-thickness keratoplasty has shown mixed results. Several studies have demonstrated the utility of BCL wear in maintaining epithelial integrity following penetrating keratoplasty.43,44 A risk for bacterial corneal ulcers was noted, however, in patients treated with BCLs after penetrating keratoplasty; this risk appeared to be intensified in immunosuppressed hosts.45

Boston keratoprosthesis. Boston Type 1 Keratoprosthesis (KPro; Mass Eye and Ear) is an artificial cornea that is placed when prognosis for a successful penetrating keratoplasty is guarded, as in patients with compromised host tissue or history of prior corneal graft rejection.46-48 Continuous BCL wear is essential for long-term management of KPro patients to maintain ocular surface hydration, minimize evaporative drying and prevent postoperative complications such as corneal melt.49-52 In order to preserve keratoprosthesis function and maintain adequate lens retention, it is imperative to establish a suitable BCL fit, with modification of contact lens parameters such as base curve and diameter often necessary.48,49,53

Corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL). This surgical procedure, which aims to stop the progression of keratoconus, necessitates the use of BCLs to promote re-epithelialization following complete removal of corneal epithelium.54-56 Due to absence of epithelium, microbial colonization and infection pose a concern.54,55 One study found that 16.7% of eyes treated with CXL experienced bacterial colonization and recommended the prophylactic use of postoperative topical antibiotics to prevent infection.54 Another concluded that forgoing BCL application as well as delaying use of steroids until epithelialization occurs may reduce risk of microbial keratitis; however, the authors noted that it was impossible to discern whether risk of microbial keratitis increased from use of BCLs, steroids or a combination thereof.55

|

|

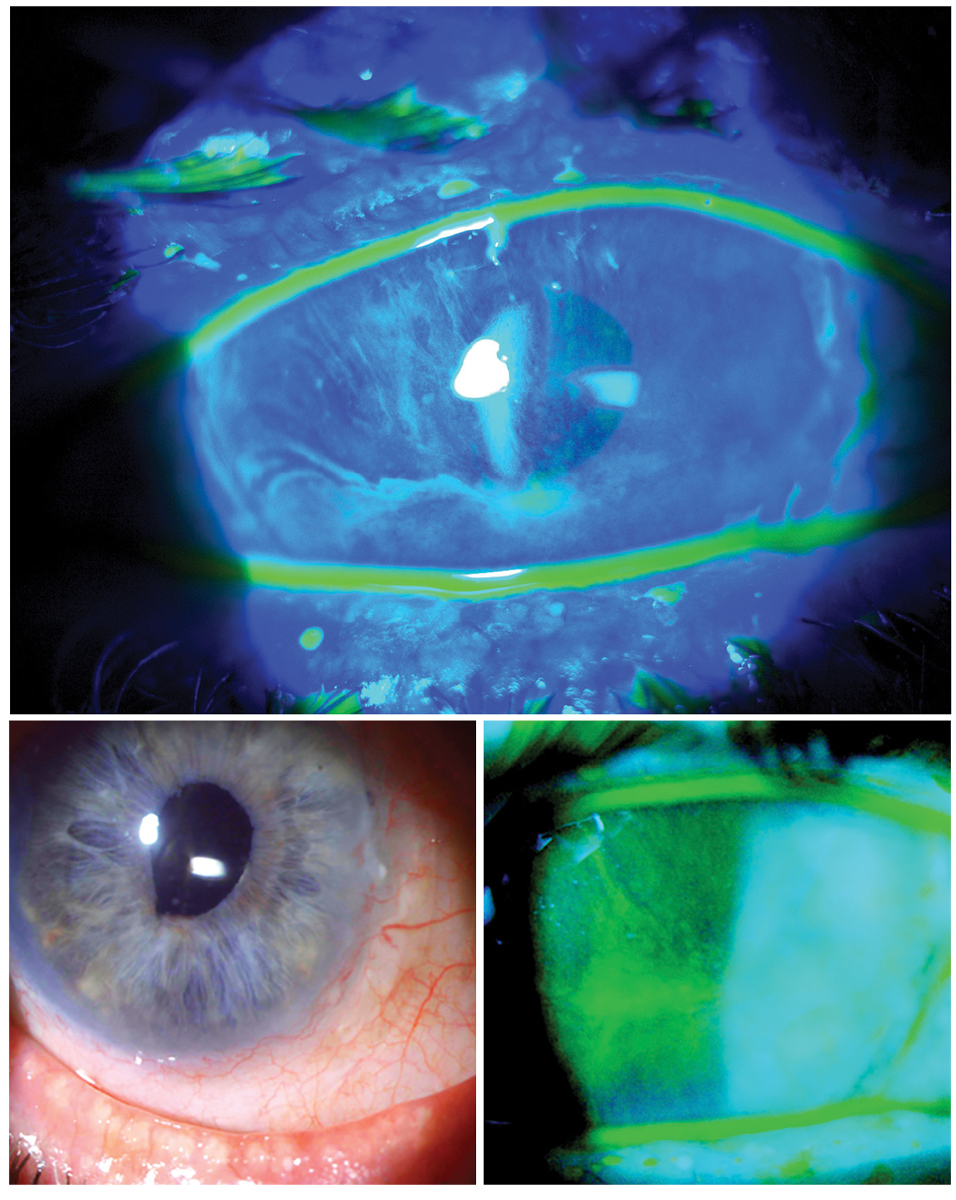

Structural concerns such as limbal stem cell deficiency may require a highly customized fit. Click image to enlarge. |

Cataract extraction. Bandage contact lenses offer ocular surface protection in the immediate postoperative period following cataract surgery.57 Patients often experience post-surgical discomfort secondary to corneal incisions.57 One 2018 study found that BCLs can successfully control postoperative pain and discomfort, protect the cornea from exposure during recovery from corneal incisions and improve delivery of antibacterial drops.57 Furthermore, medications for cystoid macular edema (CME) following cataract extraction may result in keratoconjunctivitis medicamentosa.58 In these cases, bandage contact lens wear was shown to mitigate corneal epithelial disease—which may, in turn, improve tolerance to CME medications.58

Pterygium excision. Bandage lenses have been recommended in the postoperative management of pterygium excision due to their ability to hasten corneal healing and alleviate discomfort.59-61 BCL wear, however, has not shown superior comfort post-pterygium excision when compared with patching; furthermore, studies have shown that patching confers the added benefits of relief from photophobia and improved sleep quality, albeit at the expense of binocularity and cosmesis.60,62,63

Post-trabeculectomy. Bandage contact lenses have demonstrated superior utility relative to traditional suturing and patching in the post-surgical management of trabeculectomies, which may result in complications including filtration bleb leakage and anterior chamber shallowing.64-69 The concurrent uses of topical antibiotics, steroids and cycloplegics have been recommended when covering bleb leaks with BCLs, as well as conjunctival coverage extending 2mm to 3mm superior to the limbus to prevent air bubble formation.64,65 Large-diameter BCLs have also shown efficacy in managing early onset hypotony secondary to surgical filtration procedures such as trabeculectomies, with intraocular pressures rising 5mm Hg to 12mm Hg following BCL application.70

Corneal laceration. In one case of severe laceration, bandage lens wear was shown to prevent complete extrusion of ocular contents, including of the crystalline lens, allowing for a short delay of necessary evisceration.71 In another case, a perioperative BCL was placed during pars plana vitrectomy in the setting of corneal laceration, stabilizing the anterior chamber, maintaining a closed environment and improving surgical visualization.72 In instances of small, perforating corneal injuries, BCL wear has been shown to be an effective alternative to surgical intervention with the added benefit of precluding complications associated with suturing.73

Novel and Additional Uses

Bandage contact lenses have also shown utility for improving the ocular surface in certain situations and for other conditions.

Dryness. Silicone hydrogel BCL wear can improve discomfort from ocular dryness after cataract surgery by increasing stability of tear film and promoting corneal healing.74-76 Improved TBUT scores, Schirmer 1 scores, fluorescein staining, inflammatory biomarkers, OSDI and subjective evaluation scores were noted for patients treated with BCLs.74,76

For patients with filamentary keratitis in aqueous-deficient dry eyes, higher water content, higher Dk contact lens materials have been reported to be therapeutic, while thicker, lower Dk and hydrogel materials have been noted to cause filamentary keratitis, with long-term use of BCLs being contraindicated in aqueous tear-deficient eyes.77

In patients with dry eye associated with Sjögren’s syndrome, application of BCLs has been shown to significantly improve BCVA, OSDI, corneal staining, TBUT, comfort and quality of life.75 This approach also proved superior to autologous serum drops in certain instances.75 The combination of BCL use with autologous serum drops has been suggested for the treatment of severe dryness and has further proved valuable for the recovery of persistent epithelial defects with subsequent improvement in BCVA.75,78-81

Furthermore, BCL use in sedated and mechanically ventilated patients has been shown to limit exposure keratopathy to a greater degree than ocular lubricants, with BCLs significantly promoting healing of preexisting corneal defects.82 Bandage lenses have also shown utility in the treatment of congenital cornea anesthesia, a rare clinical condition which results in impaired healing of the corneal epithelium and may progress to keratopathy and/or corneal perforation.83

Graft-vs.-host disease. Several studies report on the role of BCLs in the treatment of ocular surface disorders secondary to graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD). Ocular GVHD can result in minor conjunctivitis and/or keratoconjunctivitis sicca, or can be severe, with cicatricial findings and/or corneal perforation; superficial punctate keratopathy and filamentary keratitis are often noted.84,85 When initial treatments alone may not sufficiently mitigate symptoms or when scleral lens wear is difficult due to high cost, time or availability limitations, soft BCLs may be considered as an alternative.84,86 BCLs have been found to promptly improve subjective symptoms, visual acuity and ocular surface integrity in patients with ocular GVHD, as well as reduce frequency of topical lubricant instillation.84-86

|

|

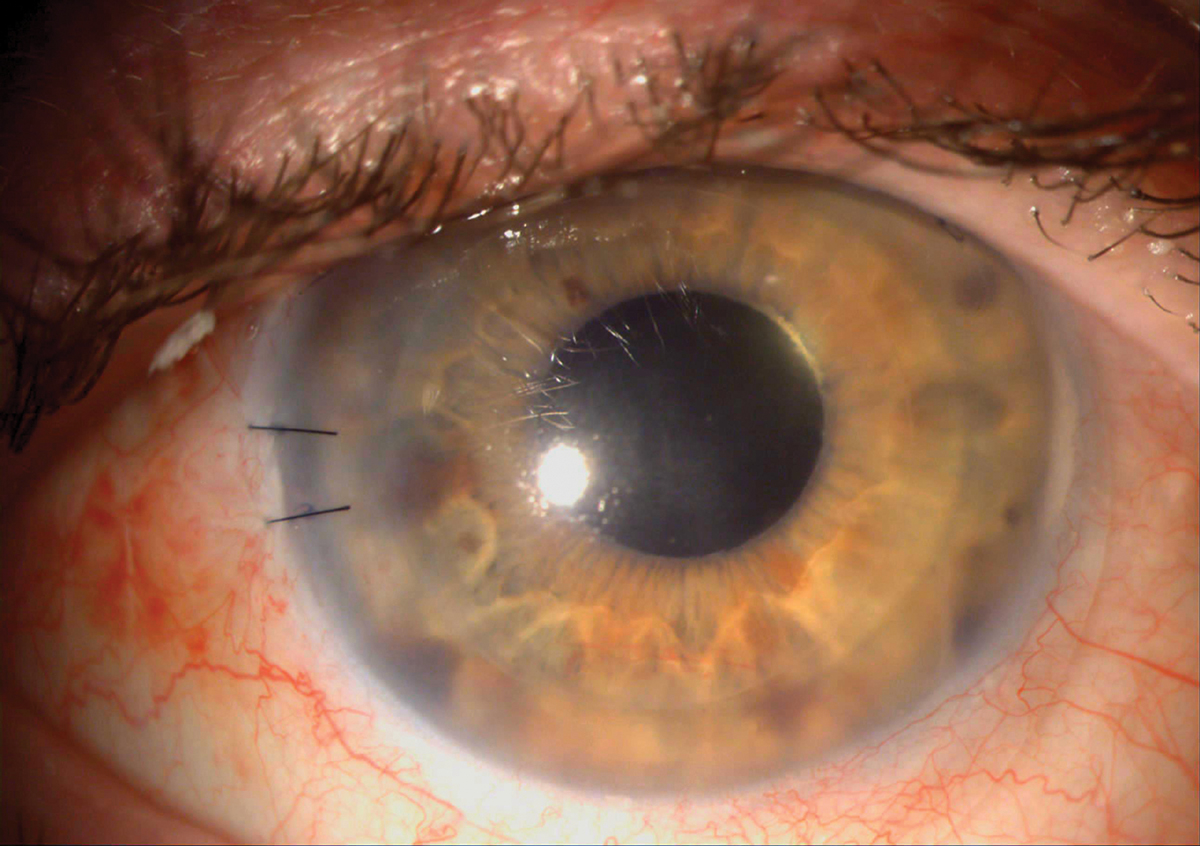

Several studies have demonstrated the utility of BCL wear in maintaining epithelial integrity following penetrating keratoplasty. Click image to enlarge. |

Bullous keratopathy. BCL wear has been shown to promote healing of this chronic corneal condition that results in formation of painful epithelial bullae secondary to endothelial dysfunction and subsequent corneal edema.86,87 BCLs prevent lid interaction with exposed corneal nerves, minimizing corneal edema and contributing to relief of pain, photophobia, blepharospasm and epiphora.86,87 SiHy material has been shown to outperform conventional soft lens materials in terms of comfort, while no significant difference was found in terms of pain relief, fit, movement or buildup of deposits.86

Infectious keratitis. Bandage contact lens use has been shown to improve ocular surface abnormalities secondary to adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis.88 In concert with adjuvant therapies including preservative-free artificial tears, topical antibiotics, ganciclovir, povidone-iodine and steroids, BCLs can promote pain relief by resolving epithelial defects, filamentary keratopathy and epithelial edema.88

Conjunctival protection. Soft BCLs have been implicated in the treatment of several conjunctival conditions. One study demonstrated the value of short-term large-diameter BCL wear in resolving symptoms of severe acute superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK), although recurrences were likely to occur and treated for the long term by other means.89 Unilateral BCL wear was found to contribute to bilateral symptom relief in SLK, possibly mediated by a bilateral decrease in reflex blinking.90 Bandage lenses have also demonstrated mechanical shielding of the cornea from irregular palpebral conjunctiva in a case of primary conjunctival amyloidosis, conferring significant symptom relief.91 Further, BCLs were shown to prevent post-surgical symblepharon reformation after chemical burn of the external eye.90

Drug Delivery

Extensive research recognizing the abilities of BCLs to function as drug delivery systems has been documented due to their superior drug bioavailability relative to eye drops and availability for use on an extended wear schedule.92-96 Eye drops confer low drug bioavailability due to precorneal loss and poor corneal absorption, leading to increased frequency of dosing, side effects and poor medication compliance.92-96

Desired properties of drug delivery devices include easy, comfortable and controlled administration over an extended period of time with preservation of vision and ocular function.93 Several types of BCL drug delivery systems have been described; these include soaking contacts in drug solution, instilling eye drops over bandage contact lenses already in place on the eye, molecularly imprinting drug site polymers onto contact lenses, loading colloidal nanoparticles onto contact lenses to control drug release, preparing contact lenses with hydrophilic and hydrophobic phases, integrating vitamin E within lenses to create drug transport barriers and incorporating microemulsions, liposomes or micelles into the contact lenses.92-96

In April 2021, Johnson & Johnson Vision Care announced FDA approval of Acuvue Theravision with Ketotifen, a drug-eluting contact lens made of etafilcon A material, intended for allergy relief. This is currently the only medication-releasing contact lens available. Despite these innovations, optical and physical properties of contact lenses may be impacted and drug-loading and release capacity remains limited, thereby limiting commercial use of drug delivery by means of BCLs.92,93

|

|

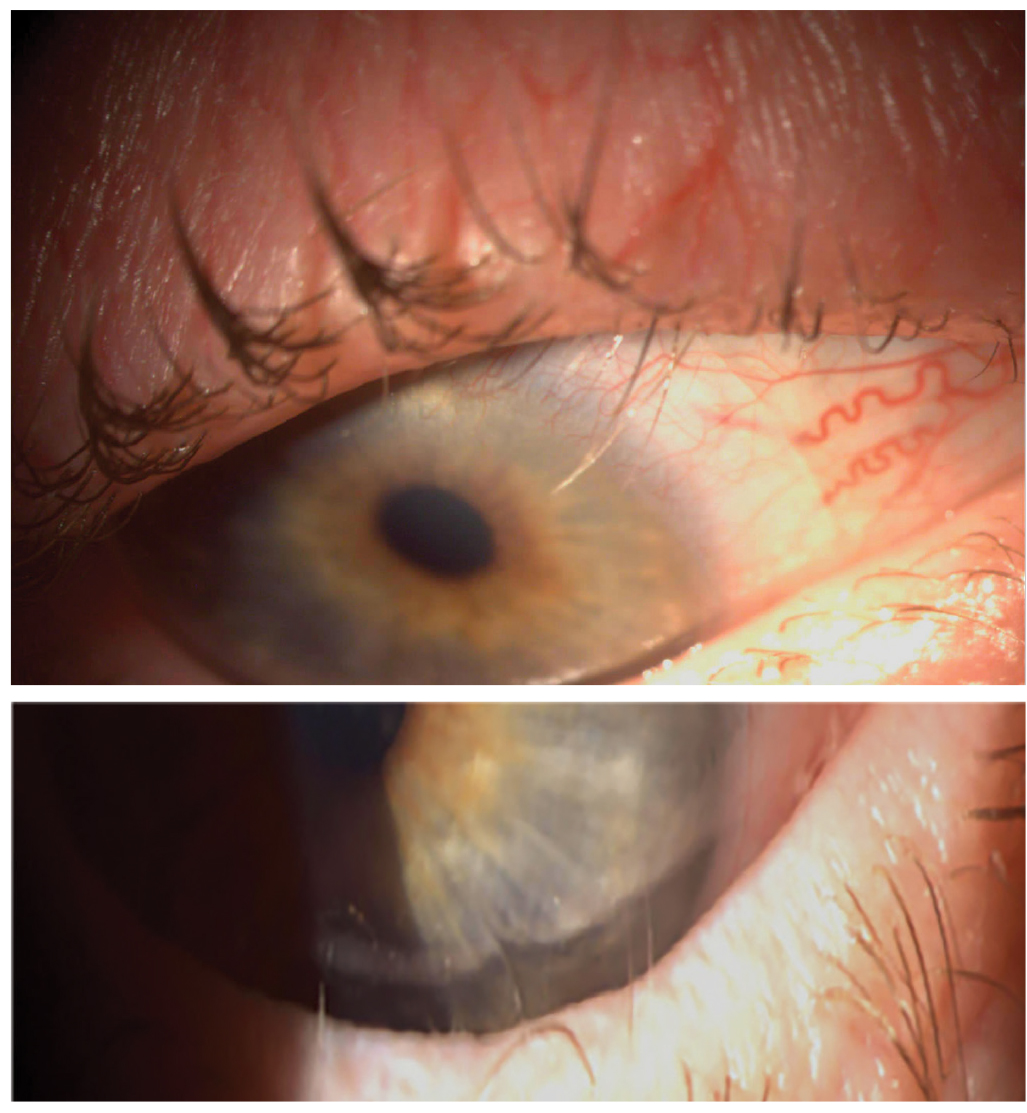

The use of BCLs has also been noted in corneal protection from the ocular adnexa, such as in the case of trichiasis. Click image to enlarge. |

Complications

While bandage contact lenses play a significant role in the protection and healing of numerous ocular surface conditions, they are often used on an extended, overnight wear schedule and bacterial colonization as well as complications including corneal edema, neovascularization, stromal infiltrates, endothelial polymegethism and infectious keratitis have been reported.97-103

In a retrospective study of 6,685 eyes from 2019, researchers found that infectious keratitis following BCL wear was diagnosed in 0.13% of eyes, which is lower than other studies.98,99 Of the eight patients diagnosed with infectious keratitis, five displayed poor compliance with BCL wear, either by overextending lens wear or noncompliance with drop regimen.99

Additional risk factors included post-keratoplasty BCL wear and older age.99 Although treatment of corneal ulcers was shown to be successful with antibiotic therapy, corneal scarring and poor visual outcomes were common.104 Biofilm formation over BCLs has also been noted in the setting of KPro. One study found prophylactic vancomycin and linezolid therapy to be relatively effective in preventing biofilm growth of BCLs worn over KPro at one month.104

Given the risks associated with bandage lenses, be vigilant to identify and prevent complications, with heavy emphasis on patient education to promote good compliance and ensure successful outcomes.98,99 Daily contact lens checks are recommended, as well as handling of lenses by the clinician.

Takeaways

With the advent of newer technology and materials, clinical use of contact lenses for the treatment of ocular surface conditions has increased considerably. Soft bandage contact lenses remain a popular option for the treatment of corneal defects and confer the added benefit of visual improvement. In many cases, BCLs can lead to complete resolution of corneal conditions and may preclude surgical intervention. Continued innovation in the manufacturing and application of contacts will likely expand their roles and result in enhanced patient outcomes.

Dr. Cherny is a resident in cornea/contact lens and ocular disease at Massachusetts Eye and Ear at Harvard Medical School.

Dr. Sherman is an assistant professor of optometric sciences (in ophthalmology) and the director of optometry at Columbia University Medical Center. She specializes in complex and medically necessary contact lens fittings and ocular disease. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry. They have no financial disclosures.

1. Arora R, Jain S, Monga S, et al. Efficacy of continuous wear PureVision contact lenses for therapeutic use. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2004;27(1):39-43. 2. McMahon TT, Zadnik. Twenty-five Years of contact lenses: the impact on the cornea and ophthalmic practice. Cornea 2000;19(5):730-40. 3. Ozkurt Y, Rodop O, Oral Y, et al. Therapeutic applications of lotrafilcon a silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses. Eye Contact Lens. 2005;31(6):268-9. 4. Ambroziak AM, Szaflik JP, Szaflik J. Therapeutic use of a silicone hydrogel contact lens in selected clinical cases. Eye Contact Lens. 2004;30(1):63-7. 5. Rubinstein MP. Applications of contact lens devices in the management of corneal disease. Eye (Lond). 2003;17(8):872-6. 6. Karlgard CCS, Jones LW, Moresoli C. Survey of bandage lens use in North America, October to December 2002. Eye Contact Lens. 2004;30(1):25-30. 7. Montero J, Spoarholt J, Mély R. Retrospective case series of therapeutic applications of a lotrafilcon A silicone hydrogel soft contact lens. Eye Contact Lens. 2003;29(1 Suppl):S54-6. 8. Kanpolat A, Uçakhan OO. Therapeutic use of Focus Night and Day contact lenses. Cornea 2003;22(8):726-34. 9. Efron N, Efron SE. Therapeutic applications. In: Contact Lens Practice (3rd ed.). Elsevier; 2018:275-81. 10. Shah C, Sundar Raj CV, Foulks GN. The evolution in therapeutic contact lenses. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2003;16(1):95-101. 11. Shafran T, Gleason W, Osborn Lorenz K, et al. Application of senofilcon a contact lenses for therapeutic bandage lens indications. Eye Contact Lens. 2013;39(5):315-23. 12. Feizi S, Masoudi A, Hosseini S-B, et al. Microbiological evaluation of bandage soft contact lenses used in management of persistent corneal epithelial defects. Cornea. 2019;38(2):146-50. 13. Van den Heurck J, Boven K, Anthonissen L, et al. A case of late spontaneous post-radial keratotomy corneal perforation managed with specialty lenses.Eye Contact Lens. 2018;44 (Suppl 1):S341-4. 14. Blackmore SJ. The use of contact lenses in the treatment of persistent epithelial defects. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33(5):239-44. 15. Tuli SS, Schultz GS, Downer DM. Science and strategy for preventing and managing corneal ulceration. Ocul Surf. 2007;5(1):23-29. 16. Triharpini NN, Jaanegara WG, Handayani AT, et al. Comparison between bandage contact lenses and pressure patching on the erosion area and pain scale in patients with corneal erosion. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2015;4(2):97-100. 17. Fraunfelder FW, Cabezas M. Treatment of recurrent corneal erosion by extended-wear bandage contact lens. Cornea. 2011;30(2):164-6. 18. Ahad MA, Anandan M, Tah, et al. Randomized controlled study of ocular lubrication vs. bandage contact lens in the primary treatment of recurrent corneal erosion syndrome. Cornea. 2013;32(10):1311-4. 19. Høvding G. Hydrophilic contact lenses in corneal disorders. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1984;62(4):566-76. 20. Mantelli F, Nardella C, Tiberi E, et al. Congenital corneal anesthesia and neurotrophic keratitis: diagnosis and management. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015;805876. 21. Kymionis GD, Plaka A, Kontadakis GA, Astyrakakis N. Treatment of corneal dellen with a large diameter soft contact lens. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2011; 34(6):290-2. 22. Ross M, Deschênes J. Practice patterns in the interdisciplinary management of corneal abrasions. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52(6):548-51. 23. Salz JJ, Reader AL, Schwartz LJ, Van Le K.Treatment of corneal abrasions with soft contact lenses and topical diclofenac. J Refract Corneal Surg. 1994;10(6):640-6. 24. Menghini M, Knecht PB, Kaufmann C, et al. Treatment of traumatic corneal abrasions: a three-arm, prospective, randomized study. Ophthalmol Res. 2013;50(1):13-8. 25. Susický P. Use of soft contact lenses in the treatment of corneal erosionsCesk Oftalmol. 1990;46(5):381-5. 26. Williams R, Buckley RJ. Pathogenesis and treatment of recurrent erosion. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:435-37. 27. Bendoriene J, Vogt U. Therapeutic use of silicone hydrogel contact lenses in children. Eye Contact Lens. 2006;32(2):104-8. 28. Sánchez-González JM, López-Izquierdo I, Gargallo-Martínez B, et al. Bandage contact lens use after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(8):1183-90. 29. Mohammadpour M, Heidari Z, Hashemi H, Asgari S. Comparison of the lotrafilcon b and comfilcon a silicone hydrogel bandage contact lens on postoperative ocular discomfort after photorefractive keratectomy. Eye Contact Lens. 2018;44 (Suppl 2):S273-6. 30. Fay J, Juthani V. Current trends in pain management after photorefractive and phototherapeutic keratectomy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2015;26(4):255-9. 31. Yuksel E, Ozulken K, Uzel MM, et al. Comparison of samfilcon A and lotrafilcon B silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses in reducing postoperative pain and accelerating re-epithelialization after photorefractive keratectomy. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(11):2569-74. 32. Duru Z, Duru N, Ulusoy DM. Effects of senofilcon A and lotrafilcon B bandage contact lenses on epithelial healing and pain management after bilateral photorefractive keratectomy. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020;43(2):169-172. 33. Mukherjee A, Ioannides A, Aslanides I. Comparative evaluation of comfilcon A and senofilcon A bandage contact lenses after transepithelial photorefractive keratectomy. J Optom. 2015;8(1):27-32. 34. Plaka A, Grentzelos MA, Astyrakakis NI, et al. Efficacy of two silicone-hydrogel contact lenses for bandage use after photorefractive keratectomy. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2013;36(5):243-6. 35. Mohammadpour M, Amouzegar A, Hashemi H, et al. Comparison of lotrafilcon B and balafilcon A silicone hydrogel bandage contact lenses in reducing pain and discomfort after photorefractive keratectomy: a contralateral eye study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38(3):211-4. 36. Taylor KR, Caldwell MC, Payne AM, et al. Comparison of three silicone hydrogel bandage soft contact lenses for pain control after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014;40(11):1798-804. 37. Taylor KR, Molchan RP, Townley JR, et al. The effect of silicone hydrogel bandage soft contact lens base curvature on comfort and outcomes after photorefractive keratectomy. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41(2):77-83. 38. Qu XM, Dai JH, Jiang ZY, Qian YF. Clinic study on silicone hydrogel contact lenses used as bandage contact lenses after LASEK surgery. Int J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(3):314-8. 39. Szaflik JP, Ambroziak AM, Szaflik J. Therapeutic use of a lotrafilcon A silicone hydrogel soft contact lens as a bandage after LASEK surgery. Eye Contact Lens. 2004;30(1):59-62. 40. Orucov F, Frucht-Pery J, Raiskup FD, et al. Quantitative assessment of bandage soft contact lens wear immediately after LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2010;26(10):744-8. 41. Xie WJ, Zeng J, Cui Y, et al. Comparation of effectiveness of silicone hydrogel contact lens and hydrogel contact lens in patients after LASEK. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8(6):1131-5. 42. Seguí-Crespo M, Parra Picó J, Ruíz Fortes P, et al. Usefulness of bandage contact lenses in the immediate postoperative period after uneventful myopic LASIK. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2018;41(2):187-92. 43. Ozbek Z, Raber IM. Successful management of aniridic ocular surface disease with long-term bandage contact lens wear. Cornea. 2006;25(2):245-7. 44. Kuckelkorn R, Bertram B, Redbrake C, Reim M. Therapeutic hydrophilic bandage lenses after perforating keratoplasty in severe eye chemical burns. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1995;207(2):95-101. 45. Saini JS, Rao GN, Aquavella JV. Post-keratoplasty corneal ulcers and bandage lenses. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1988;66(1):99-103. 46. Thomas M, Shorter E, Joslin CE, et al. Contact lens use in patients with Boston Keratoprosthesis Type 1: fitting, management and complications. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41:334-40. 47. Nau AC, Drexler S, Dhaliwal DK, et al. Contact lens fitting and long-term management for the Boston keratoprosthesis. Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40:185-9. 48. Huh ES, Aref AA, Vajaranant TS, de la Cruz J, et al. Outcomes of pars plana glaucoma drainage implant in Boston Type 1 keratoprosthesis surgery. J Glaucoma. 2014;23:e39-44. 49. Harissi-Dagher M, Beyer J, Dohlman CH. The role of soft contact lenses as an adjunct to the Boston keratoprosthesis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2008;48:43-51. 50. Dohlman CH, Dudenhoefer EJ, Khan BF, Morneault S. Protection of the ocular surface after keratoprosthesis surgery: the role of soft contact lenses. CLAO J. 2002;28:72-4. 51. Oh DJ, Michael R, Vajaranant T, Cortina MS, Shorter E. Resolution of an exposed pars plana Baerveldt shunt in a patient with a Boston Keratoprosthesis Type 1 without surgery. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2019;11:2515841419868559. 52. Beyer J, Todani A, Dohlman C. Prevention of visually debilitating deposits on soft contact lenses in keratoprosthesis patients. Cornea. 2011;30:1419-22. 53. Shorter E, Joslin C, McMahon T, De la Cruz J, Cortina M. Bandage CL fitting characteristics and complications in patients with Boston Type I keratoprosthesis surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:3464. 54. Yuksel E, Yalcin NG, Kilic G, et al. Microbiologic examination of bandage contact lenses used after corneal collagen crosslinking treatment. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(2):217-22. 55. Tzamalis A, Romano V, Cheeseman R, et al. Bandage contact lens and topical steroids are risk factors for the development of microbial keratitis after epithelium-off CXL. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019;4(1):e000231. 56. Kocluk Y, Cetinkaya S, Sukgen EA, et al. Comparing the effects of two different contact lenses on corneal re-epithelialization after corneal collagen cross-inking. Pak J Med Sci. 2017;33(3):680-5. 57. Shi DN, Song H, Ding T, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of therapeutic bandage contact lenses on post-cataract surgery patients. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11(2):230-4. 58. Jabłoński J, Szafran B, Cichowska M. Treatment of corneal complications after cataract surgery with soft contact lenses. Klin Oczna. 1998;100(3):151-3. 59. Chen D, Lian Y, Li J, et al. Monitor corneal epithelial healing under bandage contact lens using ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography after pterygium surgery. Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40(3):175-80. 60. Daglioglu MC, Coskun M, Ilhan N, et al. The effects of soft contact lens use on cornea and patient’s recovery after autograft pterygium surgery. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37(3):175-7. 61. Arenas E, Garcia S. A scleral soft contact lens designed for the postoperative management of pterygium surgery. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(1):9-12. 62. Prat D, Zloto O, Ben Artsi E, Ben Simon GJ. Therapeutic contact lenses vs. tight bandage patching and pain following pterygium excision: a prospective randomized controlled study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(11):2143-8. 63. Yeung SN, Lichtinger A, Kim P, et al. Efficacy and safety of patching vs bandage lens on postoperative pain following pterygium surgery. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(2):295-6. 64. Gollakota S, Garudadri CS, Mohamed A, Senthil S. Intermediate term outcomes of early posttrabeculectomy bleb leaks managed by large diameter soft bandage contact lens. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(9):816-21. 65. Wu Z, Huang C, Huang Y, et al. Soft bandage contact lenses in management of early bleb leak following trabeculectomy. Eye Sci. 2015;30(1):13-7. 66. Blok MD, Kok JH, van Mil C, et al. Use of the Megasoft bandage lens for treatment of complications after trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(3):264-8. 67. Shoham A, Tessler Z, Finkelman Y, Lifshitz T. Large soft contact lenses in the management of leaking blebs. CLAO J. 2000;26(1):37-9. 68. Kiranmaye T, Garudadri CS, Senthil S. Role of oral doxycycline and large diameter bandage contact lens in the management of early post-trabeculectomy bleb leak. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014208008. 69. Li B, Zhang M, Yang Z. Study of the efficacy and safety of contact lens used in trabeculectomy. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:1839712. 70. Smith MF, Doyle JW. Use of oversized bandage soft contact lenses in the management of early hypotony following filtration surgery. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1996;27(6):417-21. 71. Ramjiani V, Fearnley T, Tan J. A bandage contact lens prevents extrusion of ocular contents. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39(1):78-9. 72. Tan JJ, George MS, Olmos de Koo LC. The bandage lens technique: a novel method to improve intraoperative visualization and fluidic stabilization during vitrectomy in cases of penetrating ocular trauma. Retina. 2016;36(7):1395-8. 73. Hugkulstone CE. Use of a bandage contact lens in perforating injuries of the cornea. J R Soc Med. 1992;85(6):322-3. 74. Chen X, Yuan R, Sun M, et al. Efficacy of an ocular bandage contact lens for the treatment of dry eye after phacoemulsification. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):13. 75. Li J, Zhang X, Zheng Q, et al. Comparative evaluation of silicone hydrogel contact lenses and autologous serum for management of Sjögren syndrome-associated dry eye. Cornea. 2015;34(9):1072-8. 76. Wu X, Ma Y, Chen X, et al. Efficacy of bandage contact lens for the management of dry eye disease after cataract surgery. Int Ophthalmol. 2021;41(4):1403-13. 77. Albietz J, Sanfilippo P, Troutbeck R, Lenton LM. Management of filamentary keratitis associated with aqueous-deficient dry eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80(6):420-30. 78. Lee YK, Lin YC, Tsai SH, et al. Therapeutic outcomes of combined topical autologous serum eye drops with silicone-hydrogel soft contact lenses in the treatment of corneal persistent epithelial defects: a preliminary study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39(6):425-30. 79. Wang WY, Lee YK, Tsai SH, et al. Autologous serum eye drops combined with silicone hydrogen lenses for the treatment of postinfectious corneal persistent epithelial defects. Eye Contact Lens. 2017;43(4):225-9. 80. Choi JA, Chung SH. Combined application of autologous serum eye drops and silicone hydrogel lenses for the treatment of persistent epithelial defects. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37(6):370-3. 81. Schrader S, Wedel T, Moll R, Geerling G. Combination of serum eye drops with hydrogel bandage contact lenses in the treatment of persistent epithelial defects. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(10):1345-9. 82. Bendavid I, Avisar I, Serov Volach I, et al. Prevention of exposure keratopathy in critically ill patients: a single-center, randomized, pilot trial comparing ocular lubrication with bandage contact lenses and punctal plugs. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):1880-6. 83. Ramaesh K, Stokes J, Henry E, et al. Congenital corneal anesthesia. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(1):50-60. 84. Inamoto Y, Sun YC, Flowers ME,et al. Bandage soft contact lenses for ocular graft-vs.-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(11):2002-7. 85. Stoyanova EI, Otten HM, Wisse R, et al. Bandage and scleral contact lenses for ocular graft-vs.-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(7):e604. 86. Russo PA, Bouchard CS, Galasso JM. Extended-wear silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses in the management of moderate to severe dry eye signs and symptoms secondary to graft-versus-host disease. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(3):144-7. 87. Andrew NC, Woodward EG. The bandage lens in bullous keratopathy. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1989;9(1):66-8. 88. Uçakhan Ö, Yanik Ö. The use of bandage contact lenses in adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Eye Contact Lens. 2016;42(6):388-91. 89. Watson S, Tullo AB, Carley F. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with a unilateral bandage contact lens. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(4):485-6. 90. Van Cleynenbreugel H, Geerards AJ, Vreugdenhil W. The use of soft bandage contact lenses in the management of primary (localised non-familial) conjunctival amyloidosis: a case report. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 2002;(285):45-50. 91. Dunnebier EA, Kok JH. Treatment of an alkali burn-induced symblepharon with a Megasoft bandage lens. Cornea. 1993;12(1):8-9. 92. Maulvi FA, Soni TG, Shah DO. A review on therapeutic contact lenses for ocular drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2016;23(8):3017-26. 93. Jung HJ, Chauhan A. Temperature sensitive contact lenses for triggered ophthalmic drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33(7):2289-300. 94. Xu J, Li X, Sun F. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of ketotifen fumarate-loaded silicone hydrogel contact lenses for ocular drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2011;18(2):150-8. 95. Gause S, Hsu KH, Shafor C, et al. Mechanistic modeling of ophthalmic drug delivery to the anterior chamber by eye drops and contact lenses. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;233:139-54. 96. Bengani LC, Hsu KH, Gause S, Chauhan A. Contact lenses as a platform for ocular drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10(11):1483-96. 97. Koh S, Maeda N, Soma T, Hori Y, Tsujikawa M, Watanabe H, Nishida K. Development of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus keratitis in a dry eye patient with a therapeutic contact lens. Eye Contact Lens. 2012;38(3):200-2. 98. Saini A, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR, Cohen EJ, Hammersmith KM. Episodes of microbial keratitis with therapeutic silicone hydrogel bandage soft contact lenses. Eye Contact Lens. 2013;39(5):324-8. 99. Zhu B, Liu Y, Lin L, et al. Characteristics of infectious keratitis in bandage contact lens wear patients. Eye Contact Lens. 2019;45(6):356-9. 100. Dhiman R, Singh A, Tandon R, Vanathi M. Contact lens-induced Pseudomonas keratitis following descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38(5):379-81. 101. Liu X, Wang P, Kao AA, et al. Bacterial contaminants of bandage contact lenses used after laser subepithelial or photorefractive keratectomy. Eye Contact Lens. 2012;38(4):227-30. 102. Hondur A, Bilgihan K, Cirak MY, et al. Microbiologic study of soft contact lenses after laser subepithelial keratectomy for myopia. Eye Contact Lens. 2008;34:24-7. 103. Dantas PE, Nishiwaki-Dantas MC, Ojeda VH, et al. Microbiological study of disposable soft contact lenses after photorefractive keratectomy. CLAO J. 2000;26:26-9. 104. Hogg HDJ, Siah WF, Okonkwo A, et al. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia-a case series of a rare keratitis affecting patients with bandage contact lens. Eye Contact Lens. 2019;45(1):e1-4. |