You’ve heard the knock on optometric education: there are too many optometry colleges, pumping out too many new grads and coaxing them through the curriculum instead of holding them to appropriately rigorous standards. Though it may be a caricature, some elements ring true, say experts within and outside academia. “If you want to get into optometry school, you can,” laments one educator.

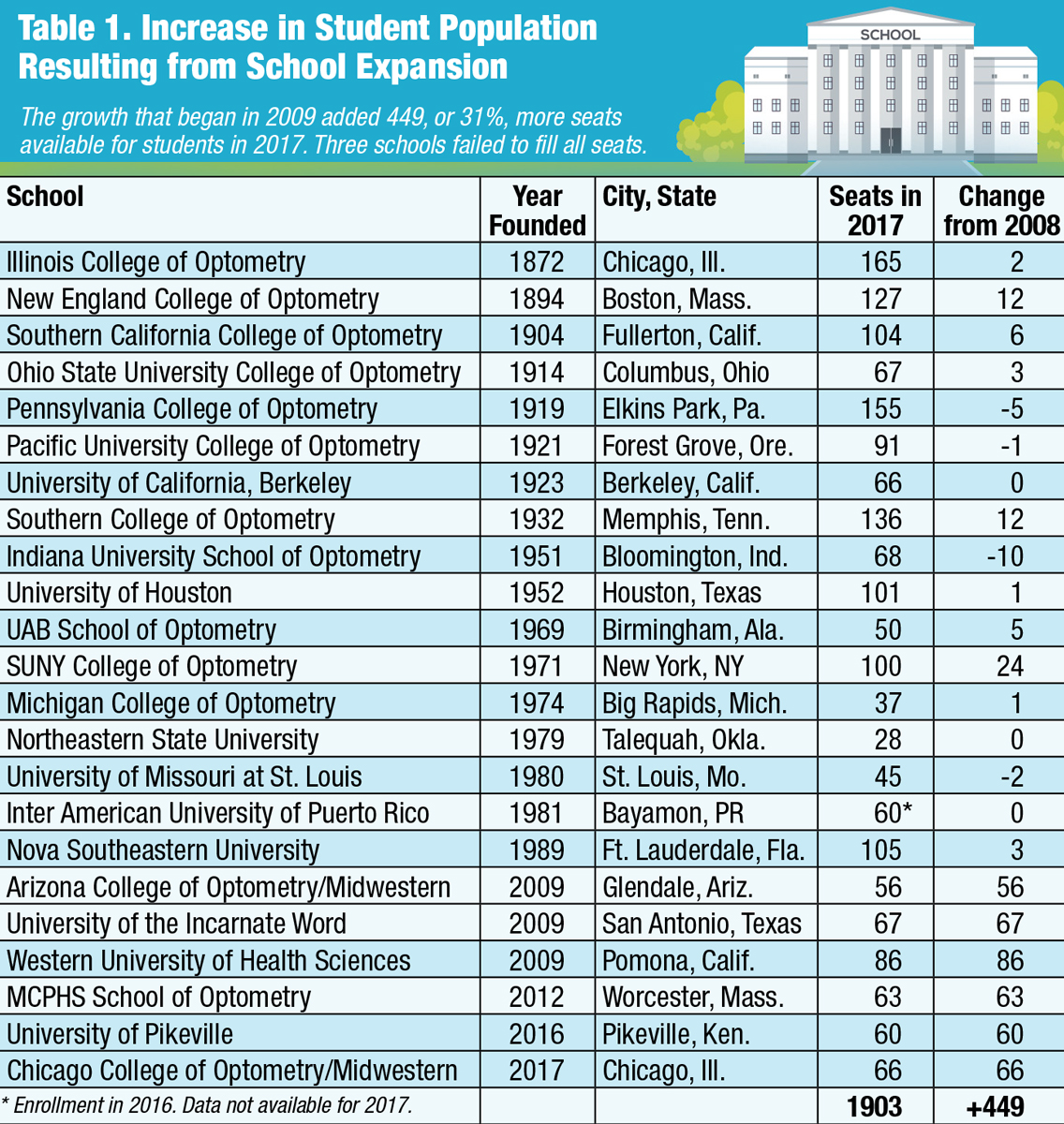

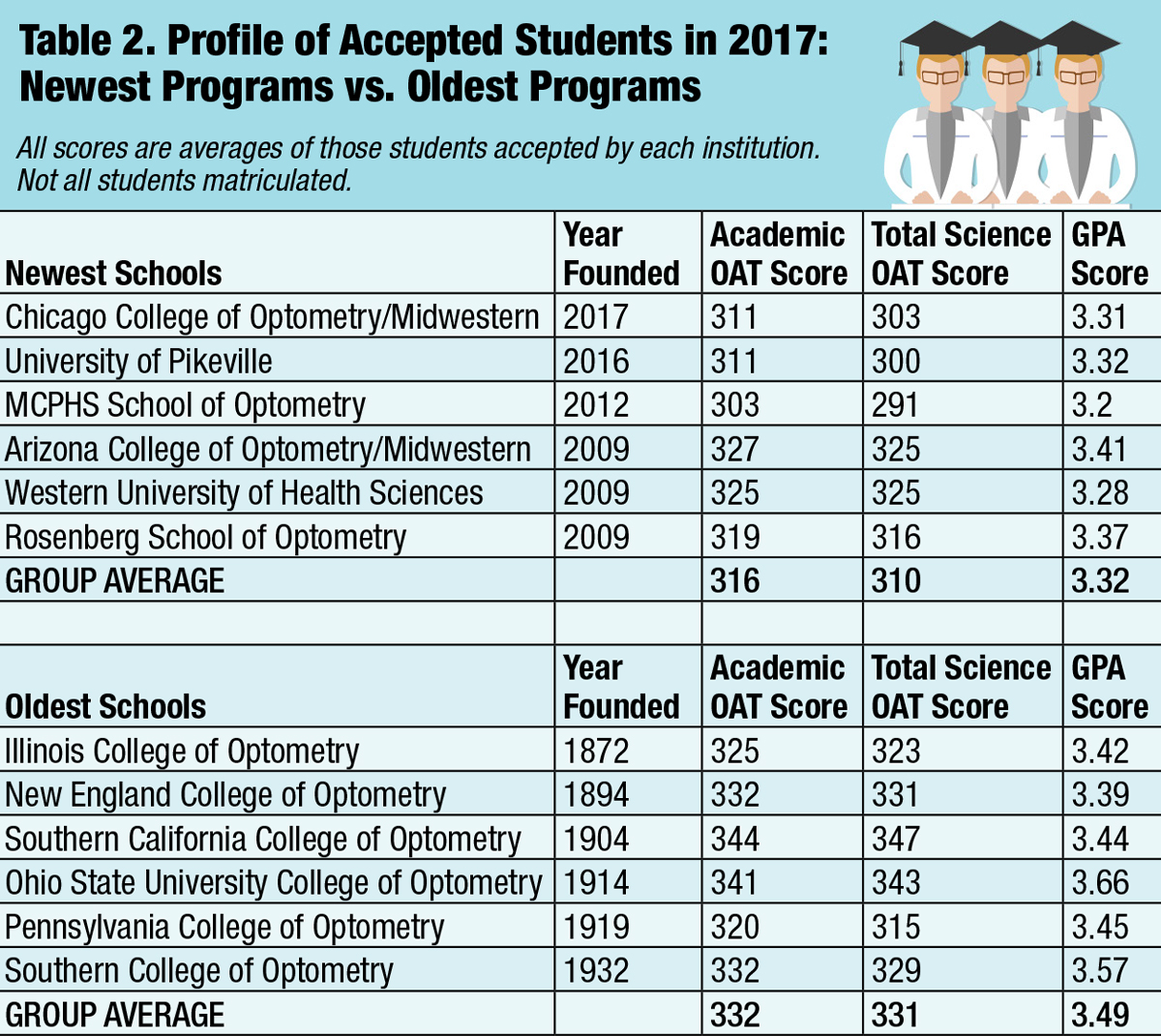

Six new optometry colleges opened in the last decade, and more are on the way. Wingate University, a private institution in North Carolina, recently announced plans to break ground on a new school of optometry, and at least two more are exploring the option.1 Established schools like SUNY College of Optometry have also expanded, adding 24 seats since 2008.

Growth itself isn’t inherently bad. A bigger footprint for optometry gives the profession more clout with legislators and insurers. But while the number of seats has gone up, applicant volume hasn’t, explains David Damari, OD, dean of Michigan College of Optometry at Ferris State University and president of the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO). In fact, recent years have even seen declines. “That’s going to make for some difficult choices,” he says. Some schools “may have to fill classes with applicants who are seriously at risk of not completing the program or passing national boards.”

Nathan Lighthizer, OD, assistant dean of clinical care services at Northeastern State University in Oklahoma, puts it this way: his institution offers seats to 28 students each year, the smallest class size in the country. With new options opening, some of the top students selected by Northeastern are likely to end up elsewhere. If, for instance, five students make that call, Northeastern has to offer spots to choices 29 through 33. It’s a sort of domino theory of admissions standards, and educators are starting to worry that it’s diluting the pool of qualified candidates.

Another concern: will new grads find productive roles in regions most in need of eye doctors, or merely bloat the ranks of well-served cities and towns? While more opportunities exist today—necessitating more optometrists—putting these new ODs where they can best serve the public remains a challenge.

Here, Review of Optometry considers recent data on the state of optometric education, what problems it presents and the safeguards being put into place to protect the discipline.

|

| Click table to enlarge. Source: ASCO. See refs. 2,3 |

More Seats, Fewer Applicants

After a 20-year lull, optometry’s current boom started in 2009 with the dual openings of schools at the University of the Incarnate Word and Western University of Health Sciences. Another four soon followed. Those six additions, plus incremental growth at established schools, expanded available seats by 31% from 2008 to 2017 (Table 1).2,3

Educators stress that while the increased number of seats may worry some, it’s the number of applicants that worries them. The applicant-to-seat ratio is trending down and stands at roughly 1.4 applicants per seat.4 ASCO reports a 4.4% year-over-year decline in applications from 2016 to 2017 but an increase of seats by 2.5% over the same period. Thus far in the 2018 cycle, applications are down 11.5% over the year prior, according to ASCO.

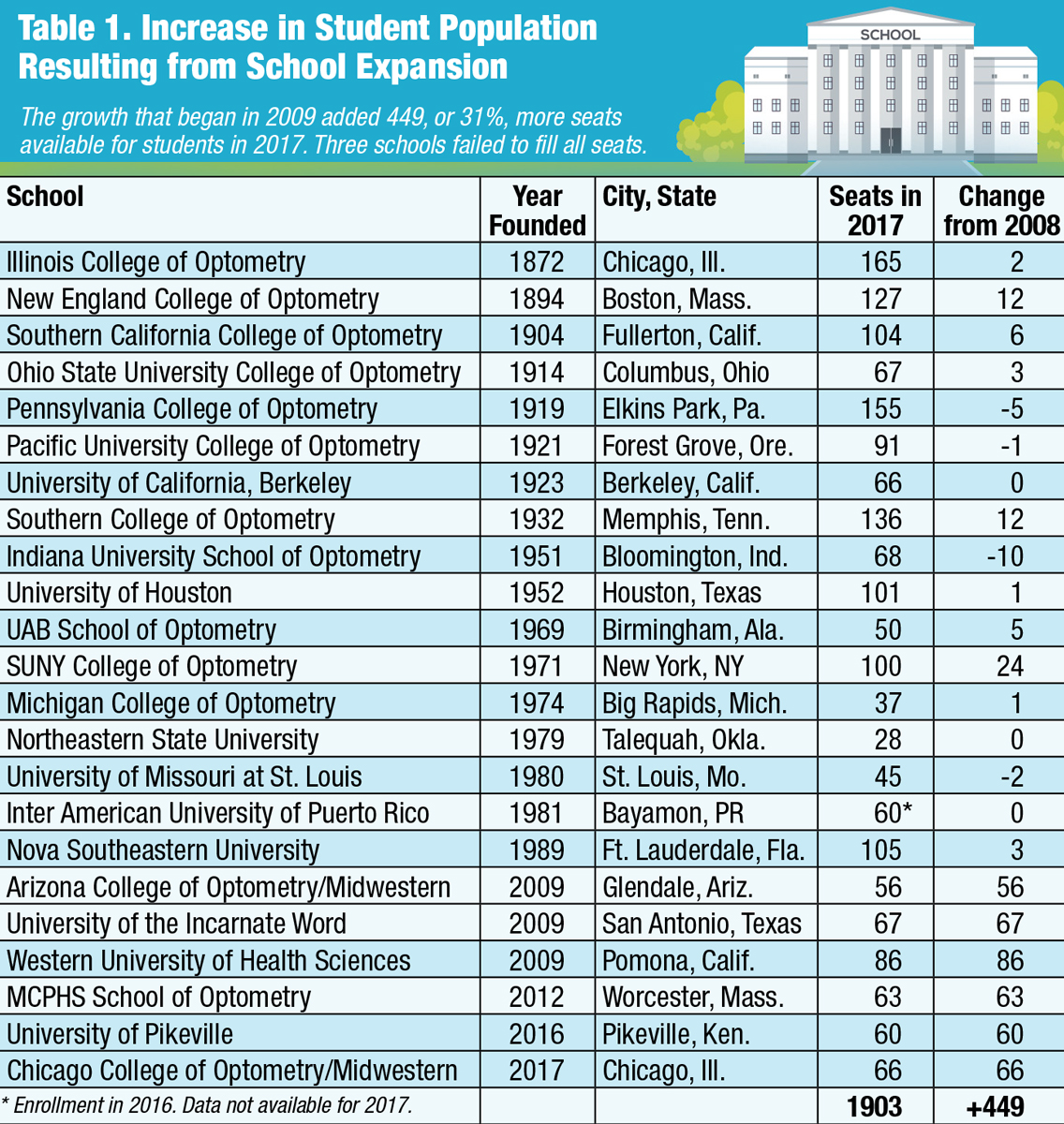

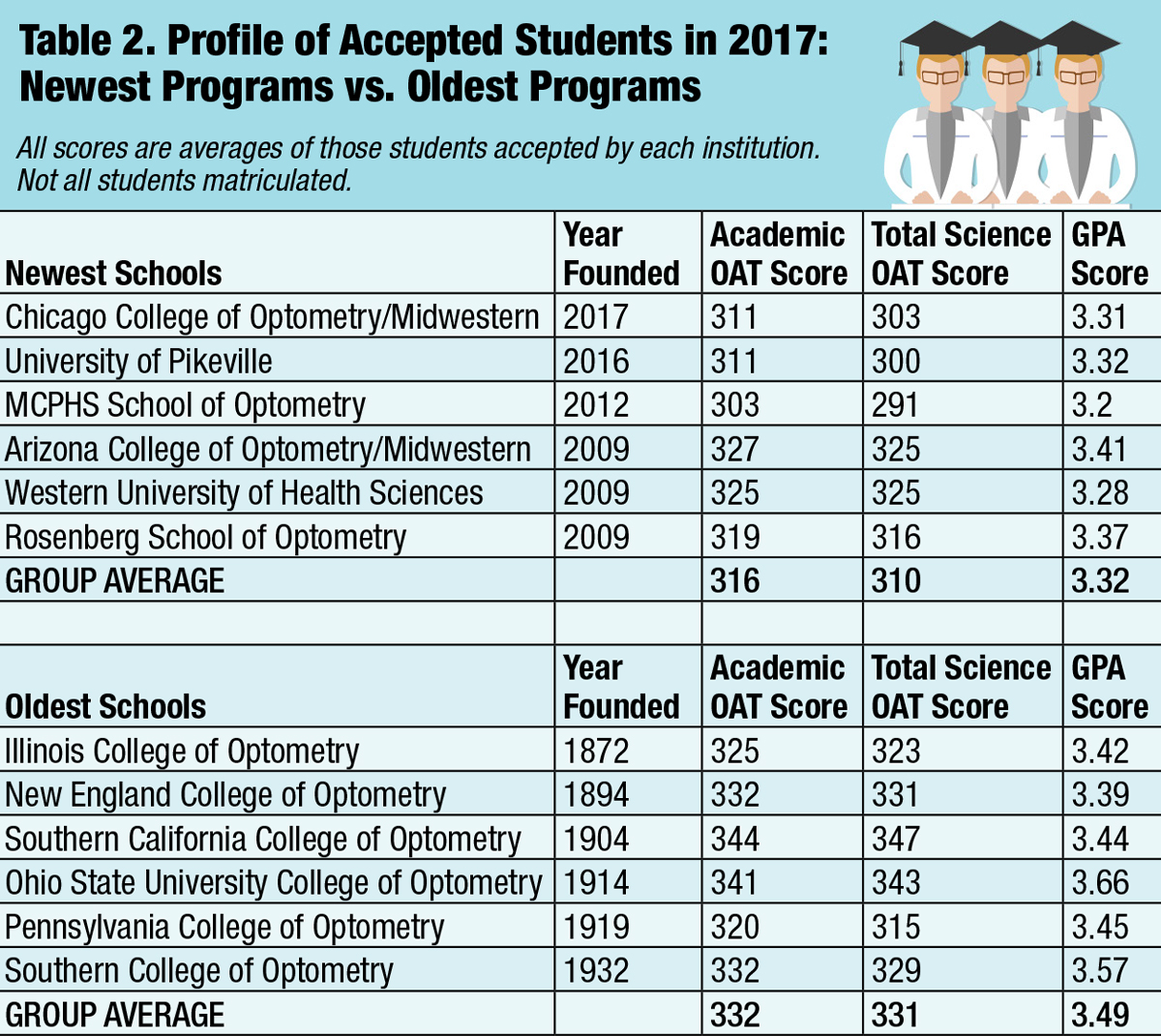

That doesn’t leave a lot of room for schools to be selective, explains Joseph Bonanno, OD, professor and dean at Indiana University School of Optometry. Some students are being accepted who otherwise wouldn’t, especially at the newer institutions. ASCO data shows that the six newest schools accept objectively lower-scoring applicants (Table 2).5 In 2017, they accepted GPA averages ranging from 3.20 to 3.41 with a group average of 3.32; for the six oldest schools, it was 3.39 to 3.66 and an average of 3.49. Of the six lowest GPAs accepted in the United States last year, five come from the newest institutions (Table 2).

|

| Click table to enlarge. Source: ASCO. See ref. 5 |

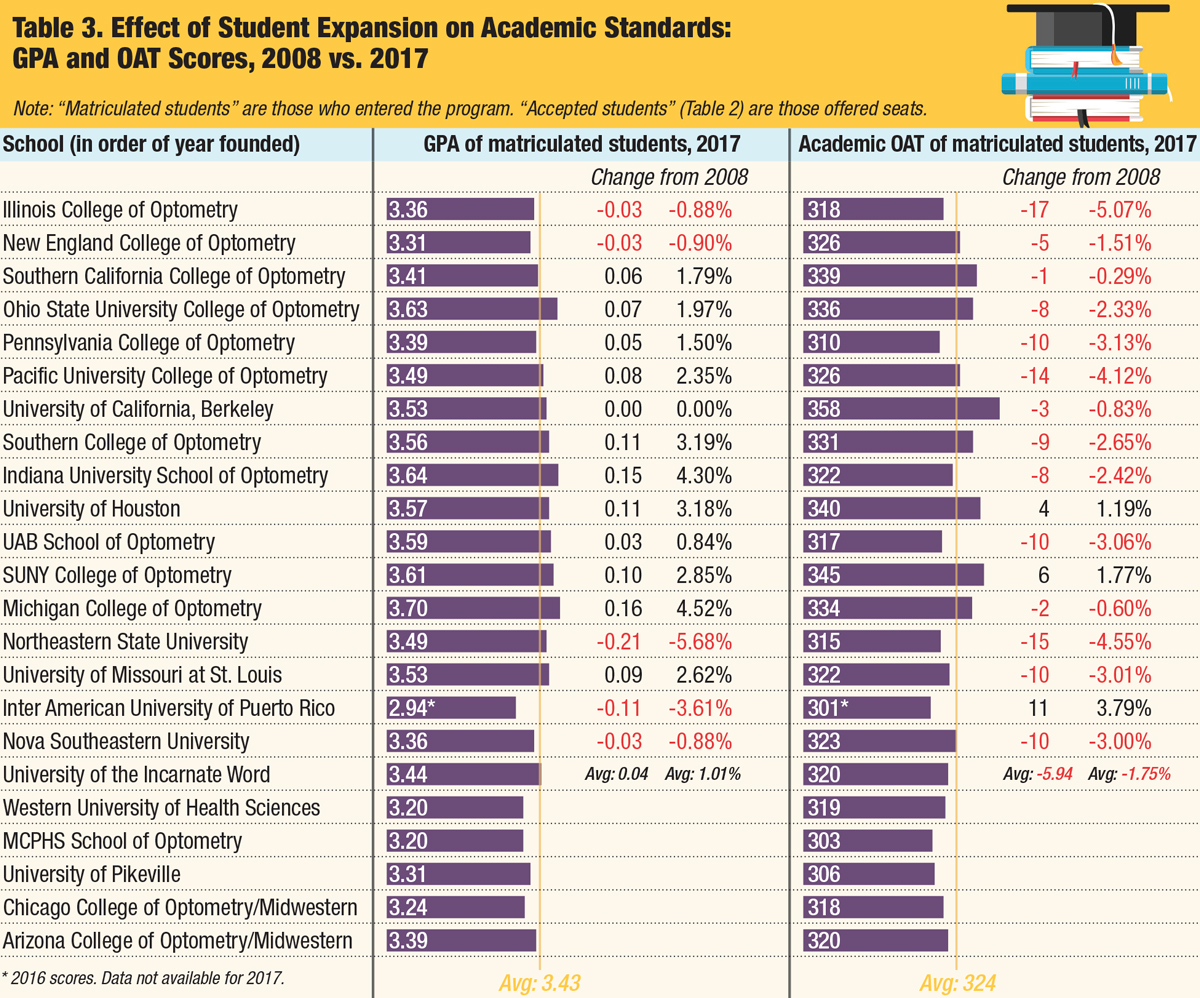

Some evidence suggests that the ripple effect of lowering admissions standards may have spread to other optometry programs, just as Dr. Lighthizer described. Students are being accepted with lower optometric admission test (OAT) scores nearly across the board compared with a decade earlier (Table 3).2,3 Averaging all changes in OAT scores (i.e., increases as well as decreases) gives an overall decline of 1.75%, but individual schools saw declines as high as 5%. Of the 17 US optometry schools that existed in 2008, 14 lowered their accepted academic average OAT score by 2017—11 by five points or greater.2,6

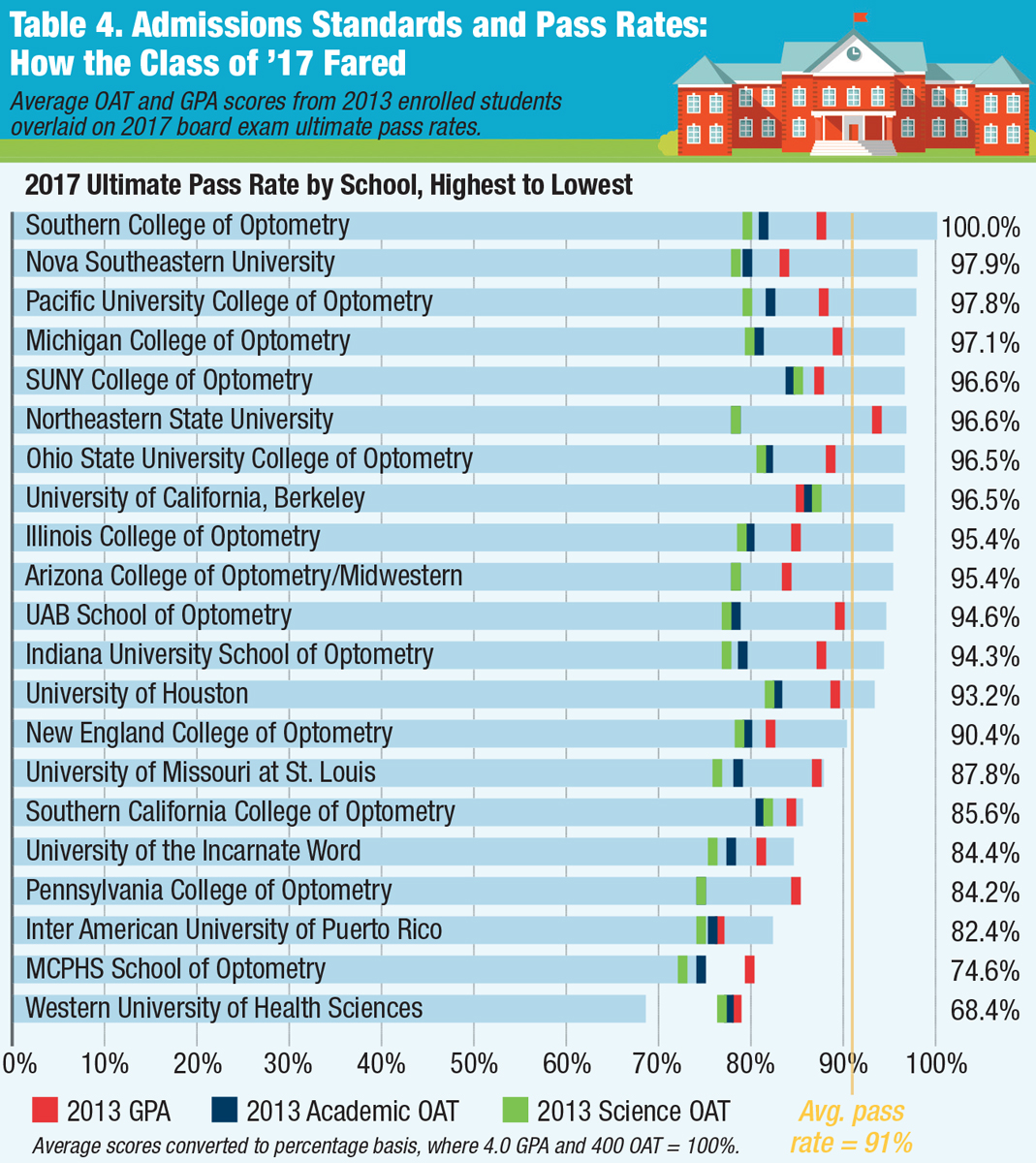

What’s the picture like at the end of a student’s college experience? Also troubling. Optometry board pass rates published in late 2017 found a national rate of 91%, with some schools falling well below the average (Table 4).6 Above-average student populations don’t always correlate with below-average pass rates. Of the bottom five, Salus University’s Pennsylvania College of Optometry (PCO), whose ultimate pass rate is 84.2%, has the largest class (152 candidates) and Southern California College of Optometry (SCCO) at Marshall B. Ketchum University is second (85.6% pass rate) with 97 candidates. But the other three are mid-range on class size, with Western University of Health Sciences hosting 76 candidates (only 68.4% pass), Rosenberg hosting 64 (84.4% pass) and Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (MCPHS) hosting only 59 (74.6% pass).6

Altogether, eight schools fell below the National Board of Examiners’ (NBOE) average pass rate. Among those were the five that accepted the lowest OAT scores in 2013 (the year the class of 2017 would have entered the program).7 However, while the connection exists on the low end of the chart, the trend doesn’t necessarily indicate that low OAT scores correlate directly with low ultimate pass rates. Take for instance, New England College of Optometry, which, at 90.4%, fell below the NBOE’s average pass rate, but in 2013 accepted an average academic OAT score of 320 and an average total science score of 318. That’s on par with the average OAT scores for the entering class of 2013 (whose academic average was 320 and average total science score was 317). Conversely, Midwestern University’s Arizona College of Optometry accepted students in 2013 with average scores of 319 (academic) and 315 (total science) (tied for fifth lowest) and a 3.37 GPA (seventh lowest) and, yet, 95.4% of its students pass boards. UAB is another example where, although its OAT scores fall below the average (academic, 315; total science, 311), 94.6% of students pass boards.6,7 This suggests that while being selective with the students who enter the program can impact the outcome, ultimately a school has the opportunity to right its students’ ship.

|

| Click table to enlarge. Source: ASCO. See refs. 2,3 |

Numbers Don’t Tell All

To wit, educators say students’ personal stories can counter the notion that lower scores make for less suitable candidates (see, “I’m More Than My GPA”).

While GPA and OAT scores can be predictors of success in optometry school, there’s a third factor that’s harder to quantify. “You can’t just look at GPA on face value, says Joseph Pizzimenti, OD, an educator on the admissions board at UIW’s Rosenberg School of Optometry. “A physics major from University of Chicago may have only graduated with 2.95,” but someone with that degree from that school “will likely perform well in optometry school,” as long as their OAT scores measure up. “If that kid can communicate during an interview, I’m going to take her every day of the week and twice on Sunday,” he says. “You do this long enough and you know where the quality [undergraduate] programs are.”

Across the country in Pennsylvania, James Caldwell, OD, dean of student affairs at PCO, agrees about the value of communication skills. “I don’t know where the study is that says you have to have a 3.7 GPA to be a better optometrist than someone with a 3.3 GPA.” PCO looks for “appropriate coursework in the appropriate combination,” he says. That is, a mix of multiple science courses, “pre-med quality work,” participation in school organizations and community service. “You want to have a nice, solid portfolio. You don’t want to be all academic and no personal skills.”

In fact, in a 2008 ASCO survey, eight schools rated students’ OAT scores “significant” in influencing their admission process, another eight rated it only “moderate” and one even said it had no influence at all. But they all required an in-person interview.3

Bright and motivated students can succeed just as well as undergraduate superstars, say educators in the trenches. But an objectively weaker pool (on purely academic measures) of candidates and rapidly evolving clinical responsibilities are causing institutions to revamp some elements of their programs, or at least contemplate doing so. Broadly speaking, three actions can keep these trends from inflicting damage to institutions, practitioners and the profession as a whole.

|

| Click table to enlarge. Source: ASCO. See ref. 6,7 |

1. Adapt

With downward pressure on admissions standards, the education community may need to enact some short-term reforms to ensure a stronger long-term outlook.

“The fact that there are more seats available while we have the same number of candidates presents a challenge,” says Dr. Damari. “And it’s difficult for some programs to decrease their class sizes.”

But if they did, it wouldn’t be without precedent. For example, in the 1980s Southern College of Optometry (SCO) did reduce its class size. “When I came in in 1980, my class had 152 students,” says Lisa Wade, OD, director at SCO’s Hayes Center for Practice Excellence. “They soon reduced it to 90 over concerns about the quality of applicants” and cut tuition by 27%. “At that time, SCO was the most expensive optometry college in the country, and they realized they were on a path that could not be sustained or continue to attract quality applicants,” Dr. Wade says. Today, SCO has 132 seats, up by only eight from 2008, when the current boom began.3

The mix of didactic vs. hands-on training might be in need of a rethink, too. “We’re ready to make the most efficient modifications to make sure our students are best prepared,” said PCO Dean Melissa Trego, OD, in a videotaped response to the NBOE board pass rate data, including ending a program that allows third-year students to work in an off-campus clinic in January.8 Now, they’ll remain on campus so they can be prepared for part one of the boards, which begins in March. She also stresses that the NBOE figures are only first-time scores. “Ultimately, when students graduate, they are able to pass part one,” Dr. Trego adds. “We’ve already started the process of developing a new curriculum which provides multiple opportunities to be tested.”

Some schools may have figured out a way to both bring in a high number of students, including those whose GPAs may drag down their average, and still see nearly every single student pass boards.

Look at Nova Southeastern University in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., which has hosted more than 100 students per class since 2011 and its average incoming GPA in 2014 was 3.36, tied for fourth lowest. How, then, have administrators managed to keep its ultimate pass rate at 97.9%? Perhaps it has something to do with how the school evaluates students on their way in.

Both Nova and Indiana University have safety nets to catch students before they fall. “We’ve created a new program wherein we identify applicants we think would struggle and we put them on a five-year path that spreads out the academic burden,” Dr. Bonnano says of Indiana University. “OD programs demand a lot of course hours, and they’re all science courses.” Undergrads aren’t used to taking five science courses at once, he notes. “We’re interested in students’ success. We want to lower our attrition rate. I think you’re going to see this popping up at other schools,” he says. “The curriculum’s gotten tougher, too.”

It may sound a bit like coddling, but ASCO President Dr. Damari doesn’t see it like that. He says it’s a way to correct an imbalance. “Students from diverse economic backgrounds may not have had the best educational preparation because of the circumstances under which they grew up,” he says. “This gives us the opportunity to bring more people from different backgrounds into the profession, which is extremely valuable for any health care profession if you’re going to serve a diverse population.”

While the students entering at the bottom of the class have a chance to catch up, those nearing graduation have an option for a different kind of fifth-year: taking on a residency. To be clear, a residency is not a fifth academic year but rather a chance for hands-on experience. Optometry colleges today “must teach at the broadest scope of practice,” says Dr. Pizzimenti. “Students need to be able to sit for any state board in the country.” That includes states such as Oklahoma, where optometrists can perform laser procedures and a nationwide trend toward optometric surgical comanagement.

Formal residency programs represent a new level of training more suited for the needs of a modern OD, with students learning a style of medical practice that would have been unrecognizable a generation ago. In 1976, the Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center in Kansas City, Mo., founded the first formally accredited one-year residency for optometrists.9 Today, approximately 235 Accreditation Council on Optometric Education (ACOE) accredited residencies place hundreds of new ODs every year into programs as broad as family practice optometry and as narrow as vision therapy and rehabilitation.9

“There’s only so much you can fit into a four-year curriculum,” explains Caroline Beesley Pate, OD, associate professor and director of residency programs at the University of Alabama’s School of Optometry in Birmingham, Ala. “Although the scope of practice has changed drastically in the last 30 years, optometric education has largely remained a four-year program,” she says. Educators have to cover the same fundamental skills as in previous eras while incorporating everything that reflects a modern scope of practice, one that extends as far as injections, lasers and minor surgical procedures. “Doing a residency enables you to further expand if you’re interested in those areas.”

“I’m More Than My GPA”As she considered what to do with her bachelor’s degree, Shannon Koenders, 26, was dissuaded by some from even considering optometry school. The native of Sioux Falls, SD, doesn’t blame them. “I’ll be the first to admit my GPA wasn’t spectacular,” she says, describing it as “just scraping 3.0.” But she comes from a large family and grew up helping her parents and siblings care for a brother with Down syndrome, something she says helped her develop the skills of a caring, attentive clinician. This spring, Ms. Koenders will graduate from the University of the Incarnate Word’s Rosenberg School of Optometry in San Antonio, Texas. In her time there, she’s achieved the academic success that eluded her in her undergraduate days and then some. In fact, she is currently seeking to specialize in caring for the vision of special needs patients, including those with Down syndrome and autism, both conditions on the rise in the United States. “Maybe I wasn’t a competitive applicant on paper,” says Ms. Koenders, reflecting on her journey into optometry. But once inside the gates, she’s developed into a member of her school’s Gold Key Honor Society, parlayed her involvement in Student Volunteer Optometric Services to Humanity into an upcoming internship, worked as an optical assistant and visited Oaxaca, Mexico, on a mission, for which she had to give eye exams in Spanish. “I’m more than just my GPA,” she concludes. |

2. Incentivize

Education reform can address the changing nature of both the applicant pool and optometric responsibilities, but those new doctors still need to find a spot for themselves in the profession. The greatest need lies in rural areas, where health care demand and resources are often at their most unbalanced.

“Central Appalachia has the highest incidences of severe vision loss from other factors such as diabetes and hypertension,” said a 2015 University of Pikeville press release announcing its intentions to launch an optometry program. “Our objective is to provide access and education to the people of the mountains and to address a critical health care need.”10

“Optometrists have sort of congregated in urban areas,” says Wingate University Vice Provost Robert Supernaw in a statement about its upcoming expansion into optometric education. “We thought that we could correct that.” The national average is 1.3 ODs per 10,000 population, says Wingate. In North Carolina, it’s just 1.1, “and many counties in eastern North Carolina have well below the national average—or no optometrists at all.” The school will include a community clinic to serve indigent local residents.1

While those university clinics provide much-needed care, they can’t meet the ballooning demand on their own. “There’s plenty of people emailing me from rural areas with job opportunities, not only within Alabama, but throughout the Southeast,” says Dr. Pate. “The question is, are these graduates willing to go where the opportunities are?” She theorizes that optometry can withstand the influx of new students if they are willing to disperse from urban centers. As a state-funded program, a portion of UAB’s support relies on accepting a higher percentage of students from within the state. But, Dr. Pate says, she knows of no real school-sponsored incentive program to keep them in that state.

Some states have experimented with incentive programs. Those help to balance the pro/con lists a new doctor draws up, but can fall short. After her own graduation from PCO, Dr. Pate’s home state of Maryland agreed to reimburse her for a percentage of her tuition if she agreed to practice there for four years. But when an opportunity at UAB presented itself, she opted to forgo the deal.

Maryland may have lost Dr. Pate, but the gambit makes sense. In their mid- to late-twenties, many recent grads aren’t only settling into a career but also into family life. Encouraging young doctors to stay in a particular area at a time when many are getting married, buying a home or perhaps having children, doesn’t necessarily ensure they won’t move after four years, or break their contract at some point before then, but it helps establish roots young doctors may be reluctant to break.

Unfortunately, Dr. Pate is not exactly an outlier. “Those kinds of programs are decreasing,” says Dr. Damari. States have found that more students are willing to pay the penalty to get out of the contract, he notes.

Urban centers offer personal and professional advantages that many new optometrists deem too good to pass up, be it quality of life improvements that come with population density or professional access to the broader health care infrastructure, which, not coincidentally, also clusters in major cities. The expanding palette of optometric practice creates in many students career aspirations ill-suited to rural areas (see, “Wanting More”).

Of the many threads that weave together to form the complex state of optometric education in 2018, this inability to match health care needs with resources in the form of human capital is perhaps the most intractable.

3. Promote

If there’s any consensus among optometric educators, it’s that optometrists must do more to raise its profile and attract more qualified candidates. “As a profession, we need to brag about who we are,” Dr. Caldwell says. “We need to embrace the diversity of practice opportunities and the diversity of educational programs.”

“If we did a better job of letting the public know why they need vision care, not just eye disease care,” says Dr. Damari, “there would be more demand out there than we could know,” for both optometric care and optometric careers. “Look at what dentistry did in the 1960s and what nursing did in the 1980s and 1990s” to raise their profiles. “Our field has really lagged behind on that and we really need to step up.”

Toward that end, Dr. Damari explains, ASCO has gone as far as to hire a public relations firm to get help growing the profession’s visibility in the eyes of the public. But, he and others suggest, there are several actions individual optometrists can take today to help in the effort, including keeping their eyes open for young patients who may have what it takes to go into optometry school and making in-roads into their communities.

Wanting More

According to Matt Geller, OD, founder of the New Grad Optometry website, “The people who put glasses up on the wall and run a little family practice—that’s going to go away.” That model is “simply over,” he says. Before optometry students even graduate, many are eyeing careers modeled after subspecialty practitioners who concentrate on areas such as dry eye, diabetes, pediatrics, glaucoma or low vision. “It really is beneficial to have that niche,” says Dr. Pate. “It puts you in a class above the average graduate. You have that extra experience under your belt and you’ll be a little more marketable, and that will open doors you might not have considered, like academics or VA hospitals.” Just look at third-year Illinois College of Optometry students Jessica Capri and Mallory Scrimger, 23 and 24, respectively. They’re well aware that optometry in the 21st century offers a buffet of opportunities instead of a cookie-cutter career. “That’s the really cool thing about this field—you can do so much with it,” says Ms. Capri, who is considering a law degree once she graduates. “The field is changing. It’s not going to be just refractions anymore. It’s becoming more and more about things like medically necessary contact lenses and it’s becoming more inter-professional. That’s one of the things that drew me to this career”—the ability to contemplate options as varied as retail, research and specialty clinics, she explains. Ms. Scrimger adds, “It’s such a multifaceted profession. I didn’t realize initially that there were so many different avenues I could go down.” ODs are even finding career paths in hospital administration. After joining the surgical comanagement team at Manhattan Eye Ear & Throat Hospital, Marta Fabrykowski, OD, noticed delays in processing. She led the effort to streamline booking and intake and delays were substantially reduced. Now, she says, she’s fed up working for the medical center—and wants to run the center. To that end, she has just enrolled in Yale’s MBA program. This diversity of opportunity could be a financial boon for optometrists. “There’s no lack of positions out there for optometrists today,” says Dr. Wade, who, as part of her position with SCO assists in plugging graduates into the working world. “We have way more opportunities than ODs” available. And, as a result, “people are offering more competitive compensation packages.” |

Inventing the Future

More new schools are coming. Although ASCO and others can advise stakeholders on the burden new educational facilities may create, optometry cannot halt private development. Those closest to the issue suggest the field grow parallel to new institutions by broadening the definition of optometry, pushing for scope of practice expansions—and trusting the next generation. “I think a lot of people are just afraid of change,” says Ms. Scrimger. “But, for our generation, maybe not so much.”

Optometry has always been a self-made discipline. Fifty years ago, a group of ambitious young ODs were dismayed to find many of the diagnostic and therapeutic skills they learned in optometry school could not legally be put into practice.11 They lobbied legislators for change and transformed optometry from a refraction-based job to a primary eye care profession. “The best way to predict the future is to invent it,” said computer pioneer Alan Kay. That’s always been optometry’s way forward.

1. Yost K. Wingate pursuing optometry school. www.wingate.edu/wingate-pursuing-optometry-school. October 9, 2017. Accessed February 2, 2018. |