A 67-year-old white male presented for a comprehensive eye exam. He reported a history of bilateral posterior vitreous detachments. He also complained of environmental ocular allergies with pronounced bulbar and palpebral conjunctival edema and itching when he worked around cattle feed or dust.

The patients systemic history was significant for hemochromatosis, sleep apnea, lymphoproliferative disease, myelodysplastic disorder, congestive heart failure, angina, osteoarthritis, venous insufficiency and hemolytic anemia.

Current medications included furosemide, terazosin, acetamino-phen, aspirin, etodolac, vitamin E, nitroglycerin, triamcinolone cream, lisinopril and potassium chloride. He also underwent quarterly phlebotomy for hemochromatosis.

Diagnostic Data

Best-corrected distance acuity was 20/20- O.D. with -1.50 -1.50 x 085 and 20/20 O.S. with -1.75 -2.00 x 093. Best-corrected near acuity was 20/20 O.U. through a +2.25D add.

Unilateral cover testing ruled out strabismus. Pupils were 4mm round and 4+ reactive to light without afferent defect. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger count O.U. Extraocular muscles were full O.U.

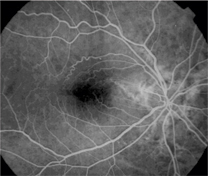

Note the prominent epiretinal membrane in this patient.

Anterior segment exam revealed dermatochalasis, pingueculae, corneal arcus, and 1+ nuclear sclerotic cataract in both eyes. There was no pseudoexfoliation and no iris transillumination in either eye. The angles were open, and anterior chambers were deep and quiet.

Intraocular pressure with Perkins tonometry was 17mm Hg O.D. and 15mm Hg O.S. at 2:55pm.

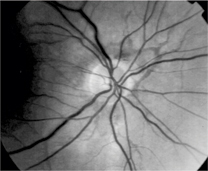

Dilated fundus examination revealed cup-to-disc ratios of 0.15, round bilaterally with pink rims and no disc edema in either eye. There was a prominent epiretinal membrane O.D., while the macula was clear O.S. Brown angioid streaks radiated outward; these were superior to the optic nerve head O.D., and superior and inferior to the optic nerve head O.S. Posterior vitreous detachments were present in both eyes.

There were no holes, tears, retinal detachments, hemorrhages, exudates, grey-green lesions, tumors or occlusions in either eye.

Diagnosis

I diagnosed this patient with angioid streaks O.U., secondary to hemochromatosis. I also diagnosed mild macular pucker (epiretinal membrane) O.D., and bilateral posterior vitreous detachments O.U.

Treatment and Follow Up

I educated the patient about the findings, and ordered a retinal consult to rule out choroidal neovascularization. I also instructed him to:

Avoid activities with the potential for eye or head trauma. I also gave him an updated spectacle prescription with polycarbonate lenses.

Monitor his vision at home with an Amsler grid.

Return to the clinic immediately if he experienced a sudden decrease in vision, flashes or new floaters. I also instructed him to return if his ocular allergies recurred. (I also recommended cool compresses and artificial tears for mild, infrequent occurrences.)

The retinal consult confirmed the presence of angioid streaks, which the specialist characterized as significantly less prominent than most. The retinal specialist also noted a moderately severe epiretinal membrane in the right eye. We decided against surgery given that the patient had 20/20- acuity in that eye and was relatively satisfied with his vision.

Discussion

Angioid streaks, which are cracks in Bruchs membrane, are one of the possible ocular sequelae of hemochromatosis. They may also occur idiopathically or in association with myopia, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Pagets disease, Marfans syndrome and sickle-cell disease.1-3

Angioid streaks are typically bilateral and asymmetrical. They appear as spoke-like, jagged, grey, red or brown lines that radiate outward from the optic nerve head. An orange peel appearance (peau dorange) may be noted temporal to the macula. This is a slightly mottled, refractile, yellow quality of the retina representing RPE disruption.2,4 The choriocapillaris is also disrupted, causing the RPE to atrophy and photoreceptors to be lost.

Brown angioid streaks radiating superior to the optic nerve head O.D.

Given the choriocapillaris disruption, RPE atrophy and photoreceptor loss, many patients with angioid streaks subsequently develop dry macular degeneration. Vision loss may occur when the cracks in Bruchs membrane extend into the macula.2 The cracks allow choroid-al neovascular membranes to devel-op, which may form scars or result in subretinal hemorrhage. Approx-imately 14% of patients with angi-oid streaks develop subretinal neo- vascularization.2

Proper management involves yearly dilated examinations. You must be vigilant in detecting the formation of choroidal neovascularization. Recommend polycarbonate lenses due to their high-impact resistance in the event of ocular trauma, and counsel the patient to avoid contact sports or situations that can result in such trauma. Also instruct patients to avoid smoking, a risk factor for CNV development. Instruct the patient on how to use the Amsler grid at home.

Fluorescein angiography is indicated if you suspect choroidal neovascularization. The streaks generally appear hyperfluorescent. However, early in the course, they can mask choroidal fluorescence. This is because angioid streaks begin as thickened, calcified areas of Bruchs membrane prior to disruption of the choriocapillaris, and loss of RPE and photoreceptors.2,4

Prophylactic photocoagulation of angioid streaks is contraindicated because this can further decompensate Bruchs membrane and promote the development of neovascu- lar nets.2 Argon laser photocoagulation is currently the most common option to abort the developing neovascular net.2 Other options that have shown potential for future treatment include submacular surgery, macular translocation, photodynamic therapy, radiation and anti-angiogenic pharmaceuticals.1

Angioid streaks are also associated with the presence of vascular abnormalities, such as large vascular loops that represent chorioretinal arteriovenous communications. They can also be accompanied by buried drusen of the optic nerve head; the incidence of these is 20-50% higher in these patients than in the normal population2,5

About 50% of cases of angioid streaks are associated with Pagets disease, PXE or sickle-cell hemoglobinopathy. Other possible etiologies include Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, hemochromatosis, diabetes, hemo-lytic anemia, hypercalcinosis, hyperphosphatemia, lead poisoning, high myopia, neurofibromatosis, Sturge-Weber syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, acromegaly and polyposis with congenital hypertrophy of the RPE.2

Our patients angioid streaks were caused by hemochromatosis, a condition of excess iron (greater than 400ug/100mg wet liver weight).6 Hemochromatosis may also be indicated by serum iron greater than 250ug/dl, serum ferritin greater than 500ng/ml or transferrin saturation approaching 100%.6 Hemochromatosis is the single most common genetic disorder in people of northern European descent.7 Three of every 1,000 people in the United States have it.8

Hemochromatosis is a potentially fatal, but treatable disorder that can be primary and inherited. It may also occur secondary to excessive iron intake, multiple blood transfusions or increased iron absorption.6,9,10

Routine blood work will not reveal hemochromatosis. Useful lab tests include serum iron, total iron binding capacity, transferrin, hemoglobin, hematocrit, ferritin, transferrin iron saturation percentage, liver biopsy and genetic testing for mutations.11

Hemochromatosis is treated by phlebotomy, one pint one to two times weekly for months until normal iron levels are established. The patient will need to continue this course life-long, about one pint every four months. Abdominal pain and skin bronzing usually clear promptly with treatment, but arthritis, hypogonadism and cirrhosis usually do not improve once established.6 Severe side effects such as hemolysis, anaphylactic shock, septic shock and metabolic disturbances are possible (and sometimes fatal) complications of repeated transfusions.6

A recent study at the University of Alabama found that many doctors know little about hemochromatosis diagnosis and treatment.12 Given the potentially life threatening nature of hemochromatosis, we must rule out this and other systemic conditions associated with ocular angioid streaks before diagnosis and treatment. Lack of knowledge could cost a patient appropriate and timely treatment or even their life.

The patient continues to be monitored at the clinic. Choroidal neovascularization has not developed. He continues to undergo quarterly phlebotomy.

Dr. Cowden practices at Bergstrom Eye and Laser Clinic in Fargo, N.D.

1. Bailey Freund K, Yannuzzi L. www.vrmny.com. Vitreous-Retina-Macula Consultants of New York.

2. Alexander L. Primary Care of the Posterior Segment. 2nd ed. Norwalk, Connecticut: Appleton & Lange, 1994:300-2.

3. Tasman and Jaeger. Duanes Clinical Ophthalmology on CD-ROM. 2000 Edition.

4. Spalton D, Hitchings R, Hunter P. Atlas of Clinical Ophthalmology. 2nd ed. Mosby, Year Book Europe Ltd. Wolf Publishing, 1994:16.16-16.17.

5. Secretan M, Zografos L, Guggisberg D, Piguet B. Choroidal vascular abnormalities associated with angioid streaks and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998 Oct;116(10): 1333-6.

6. Cotran R, Kumar V, Robbins S. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: W.B. Saunders Company, 1989:950-53.

7. Fuchs J, Podda M, Packer L, Kaufmann R. Morbidity risk in HFE associated hereditary hemochromatosis C282Y heterozygotes. Toxicology. 2002 Nov 15; 180(2):169.

8. www.merckmedicus.com

9. Britton RS, Fleming RE, Parkkila S, et al. Pathogenesis of hereditary hemochromatosis: genetics and beyond. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2002 Apr;13(2):68-79.

10. Salonen JT, Tuomainen TP, et al. Role of C282Y mutation in hemochromatosis gene in development of type 2 diabetes in healthy men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000 June 24; (320):1706-7.

11. Murtagh LJ, Whiley M, Wilson S, et al. Unsaturated iron binding capacity and transferrin saturation are equally reliable in detection of HFE hemochromatosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002 Aug;97(8):2093-9.

12. Acton RT, Barton JC, Casebeer L, Talley L. Survey of physician knowledge about hemochromatosis. Genet Med. 2002 May-Jun;4(3):136-41.