St. Louis native Frank Fontana, OD—called “Uncle Frank” by hundreds of peers and friends throughout optometry—earned his nickname by acting as a mentor to countless optometrists. Through advocacy and his own cutting-edge practice, he sculpted the very model of the modern-day optometrist: a new breed simultaneously skilled in vision correction, contact lens fitting, disease diagnosis and treatment. He died in Las Vegas on October 3 at age 96, after suffering a stroke a few days earlier while in town for the Vision Expo West conference.

|

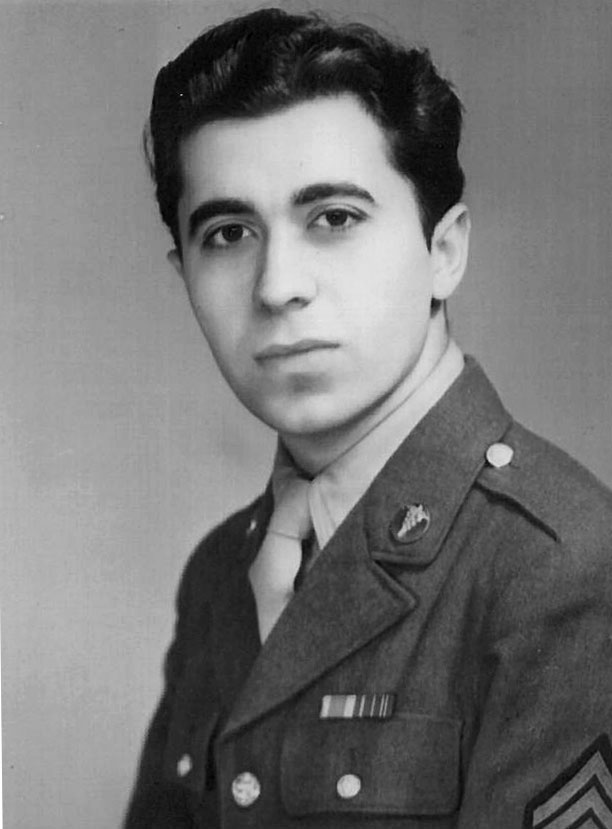

| Dr. Fontana's war service entitled him to a college education under the GI Bill. He studied at Illinois College of Optometry. |

In his youth, he served in World War II, spending 35 months in the Army, 28 of those stationed in Europe. When he returned to St. Louis, his father introduced him to an optometrist and he was inspired to join the profession. Dr. Fontana graduated from Illinois College of Optometry in 1949 and opened his practice the following year.

“Contact lenses as we know them now didn’t really exist yet,” he recounted in a 2016 interview with Review of Optometry. He may not have known it at the time, but he would soon become one of optometry’s most knowledgeable professionals on the devices, sought out by doctors and manufacturers alike.

Dr. Fontana took on leadership positions in several groups, including the Missouri Optometric Association and the American Optometric Association (AOA). He founded the Contact Lens & Cornea Section of the AOA and co-founded the Heart of America Contact Lens Society.

He established a nationally known study group, The Eyecare Marketing and Management Group (commonly known as “The Nephews and Nieces”). In a long and distinguished career, he worked alongside optometric publications, manufacturers and educators, and attended industry conferences until the day he died.

|

| Dr. Fontana photographed at Vision Expo West 2018, his last public appearance. |

Outreach and Optimism

Several optometrists tell a familiar story of encountering Dr. Fontana for the first time at a conference and being instantly invited to dinner.

Jack Schaeffer, OD, of Alabama met him 35 years ago and was immediately given a helping hand. “When I began practicing,” says Dr. Schaeffer, “Uncle Frank sent me a package that included all his contact lens fees and a recording of how to become a contact lens specialty practice. What a wonderful act of kindness. It became my practice guidelines.”

John Schachet, OD, of Colorado recalls being berated by a more established OD in his early days on the speaking circuit, only to have Dr. Fontana take him out for a conciliatory drink. After that, the pair remained close for 42 years, even vacationing with their families together.

Rosenberg School of Optometry’s Joseph Pizzimenti, OD, says that once after a lecture, he was approached by Dr. Fontana, who told him, “‘Wow, I didn’t realize someone could talk for two hours about the choroid. I learned something.’ For him to say he learned something from me, that blew me away,” he said.

Dr. Fontana was outgoing, avuncular and a good listener who rarely interrupted. When asked about his personality, his many ‘nieces and nephews’ almost unanimously land on the same word: optimistic.

“In all my conversations with him, I never once heard him say a foul word about anybody. That’s a rare characteristic,” says friend Kirk Smick, OD, of Georgia.

In addition to his noteworthy kindness, “Frank was the best at networking,” explains Dr. Schachet. “He got to know people in research and development departments of the contact lens manufacturers, and would use that to open the door and connect doctors to study opportunities.”

He was also known to advocate for up-and-comers on the lecture circuit. A word from him could go a long way, and he was generous with his support, optometrists say.

A Friendly Phone Call When I Needed ItBy Jim Sluck, Director–Optometric Market Development, Shire Ophthalmics People say that when you’re in eye care, you never leave for good, and perhaps that’s so as I find myself back after a two-year detour into dermatology. During those first weeks in an unfamiliar world, there were moments when I wondered what I was doing in such a foreign place surrounded by people and doctors I didn’t know... and then the phone rang. Uncle Frank was the first call I received in my new position. He wanted to know about my work and my reasons for moving to dermatology, and he encouraged me in my new life. It was one of the few calls I got from my eye care family. At the end of that call, Uncle Frank—same as any blood relative would do—congratulated me on the big new job and wished me continued success in my career. But as only Uncle Frank could do, he also said, “Well, Jimmy, maybe you’ll come back to optometry some day,” in the tone a relative might use when hearing you’ve moved out of your home town: proud but wistful, hoping this wasn’t truly goodbye. When I decided to come back to eye care, he was one of the first to welcome me with open arms and a warm, knowing smile. He called me ‘nephew’ after our first meeting 16 years ago, and today we are all poorer for the passing of our Uncle Frank. |

Everybody’s Uncle

Dr. Fontana and his wife Dorris (who died in 2007) had two sons, Donnie and Frankie, but his colleagues say he viewed optometry itself as another member of the family. Uncle Frank could never make his way through an exhibit hall at any convention, his friends say. Too many people stopped to greet him, and he’d speak to each one. “Our meetings will never be the same with his absence,” says Dr. Schaeffer.

At Review of Optometry editorial board meetings, he routinely requested everyone introduce themselves to each other. Those are the kinds of moments that made him ‘everybody’s uncle.’ He was brimming with positivity and knew everyone’s name, and their spouse’s and children’s names. “As passionate as he was about the profession, he realized there was life beyond optometry and was always careful to keep track of us personally, like we were truly were all his nieces and nephews,” adds Dr. Pizzimenti.

“We’ll miss the kindness and gentle manner of our beloved friend and colleague, but his impact on us will always remain,” says James Henne, Review of Optometry’s publisher. Dr. Fontana was a contributor to Review for decades and someone Mr. Henne frequently consulted. Calling him “one of the most inspiring leaders and icons in optometry for almost 70 years,” Mr. Henne notes that Dr. Fontana changed the profession for the better and touched every individual he was associated with. “Uncle Frank’s last days were spent with the industry and people he loved. He’s with Dorris now looking down on us and watching over all of us.” Mr. Henne also notes with admiration the devotion showed by his son, Frankie Fontana, who “took such good care of him and adored him.”

The honors he received have been countless, including a call out on the floor of the Missouri Statehouse, where the governor—a patient of his—told officials Dr. Fontana was the reason he could see at all.

To memorialize Dr. Fontana’s influence, Review of Optometry will name its annual career achievement award in his honor. Begun in 2014—with Dr. Fontana himself as the first recipient—the award “recognizes individuals who made it their life’s work to improve and strengthen the profession,” Mr. Henne says. Given out each year during the SECO conference, it will now be called the Dr. Frank Fontana Career Achievement Award.

The profession will spend the next few months honoring his legacy, but “he wouldn’t want anybody to grieve,” Dr. Schachet says. “He’d want them to think about the good things he did.”