Annual Cornea ReportCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: A CXL Guide For the Surgically Savvy Understanding Corneal Nerve Function—and Dysfunction (Earn 2 CE) |

It is important for both you and your office staff to feel comfortable handling these emergency patients who require foreign body removal—from start to finish. This article discusses the step-by-step process of triaging, scheduling, examining, treating and following patients with a foreign body.

|

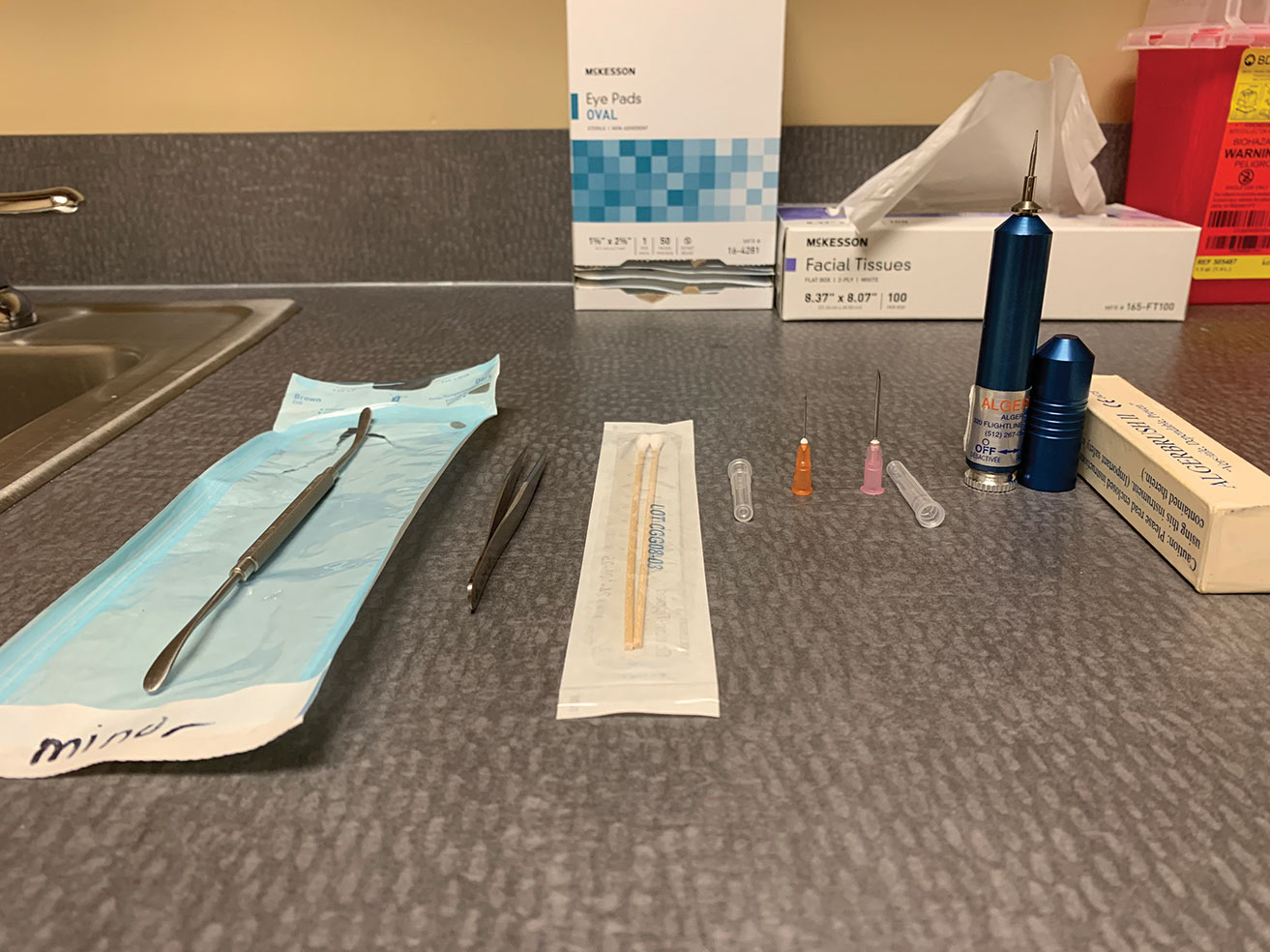

| Fig. 1. The foreign body removal toolkit includes a spud, jeweler’s forceps, cotton swabs, small-gauge needles and an Alger brush. Click image to enlarge. |

Office Prep

Most optometrists have all the tools they need to care for patients with corneal foreign bodies. The entrance tests are common practice for other conditions and include extraocular motilities, pupillary testing and confrontation visual fields. Abnormalities in these could be further indicators of orbital/globe penetration or full penetrating foreign bodies.

Other standard tests for suspected foreign body include documenting the entering visual acuities prior to any procedure and noting any pre-existing issues of amblyopia or decreased vision.

For all initial testing, train technicians to handle foreign body removal patients with “no touch” to avoid further irritating the eye or the cornea. Ocular pressures can be checked after the slit lamp exam has been performed, ensuring it is safe. If the foreign body is embedded within the cornea centrally or there is concern for an open globe, it may be best to avoid checking the pressure.

During the slit lamp exam, a topical anesthetic will keep your patient more comfortable, while sodium fluorescein and a cobalt blue filter will help you examine the eye and detect any foreign bodies, wound leakage or a full penetrating injury. If the patient is struggling to keep their lids open, a lid retractor or lid speculum may be necessary.

|

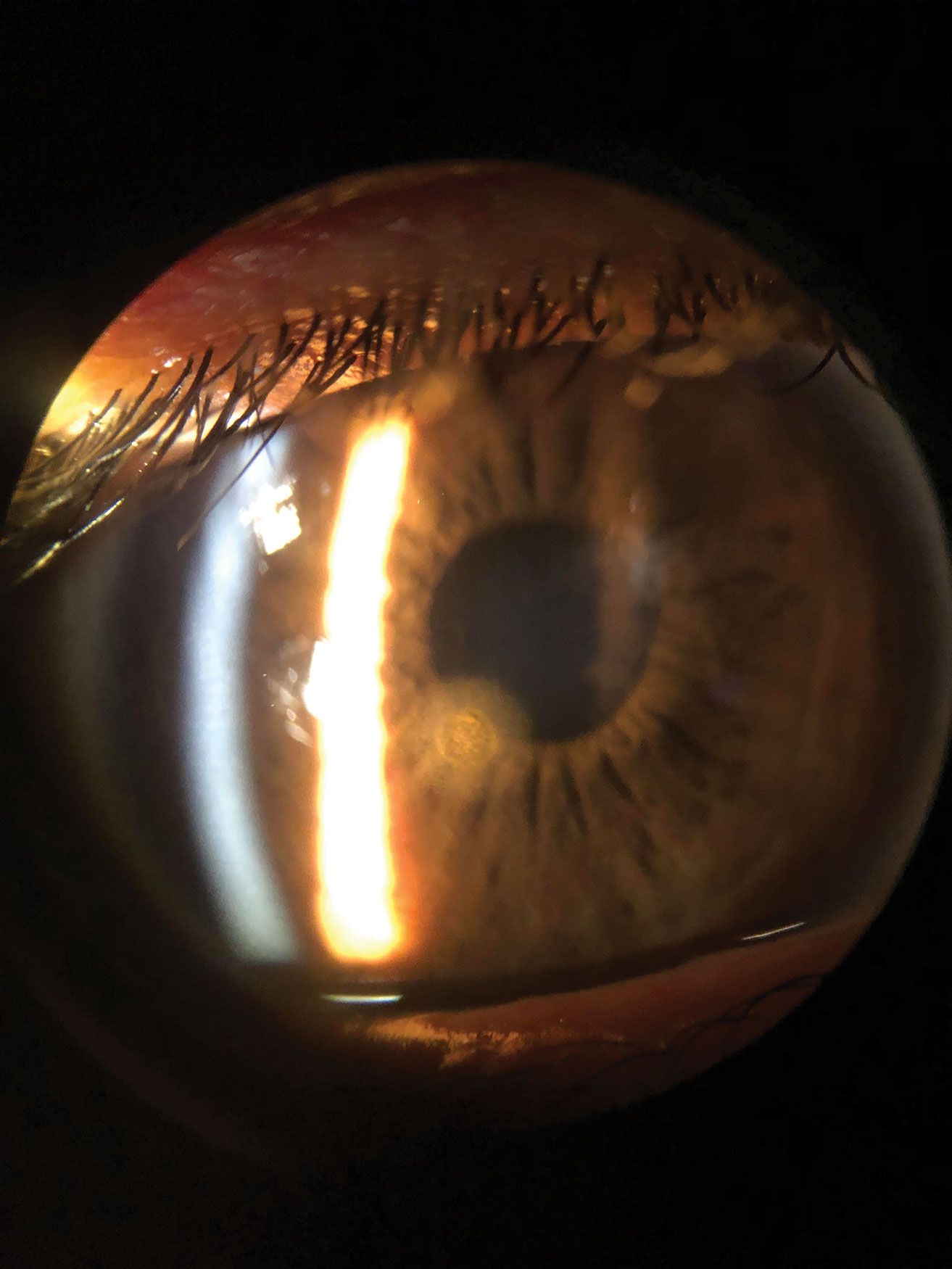

| Fig. 2. This is a patient’s cornea immediately after removal of a metallic foreign body but prior to rust ring removal. The object was superficial enough that it was removed with a sterile cotton swab after anesthetizing the patient’s eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Clinicians should stock a few different handheld tools in the office to remove various foreign bodies (Figure 1):

- Superficial or loosely embedded cornea and conjunctival foreign bodies – The simplest method to remove loose pieces of material may be using only irrigation with sterile saline solution. If that isn’t sufficient, a sterile cotton swab, spatula, spud or a small 25-gauge needle are all useful options. A magnetic spud is quite useful for metallic foreign bodies because you can often remove the object—and any residual metallic flakes—with little to no damage.

- Deeper within the corneal stroma – A spatula, spud or a 25-gauge needle are also good options here; while a spud or spatula reduces the risk of perforation, a needle often causes less damage to surrounding tissue.

- Protruding corneal and conjunctival foreign bodies – While any of the other methods mentioned may also be used, jeweler’s forceps is an excellent option, as it may allow you to grasp the edge of the object and remove it.

- Corneal rust ring – This will require an Alger brush to remove.

In addition, stock a topical antibiotic to apply before and after any procedure to ward off infection.

|

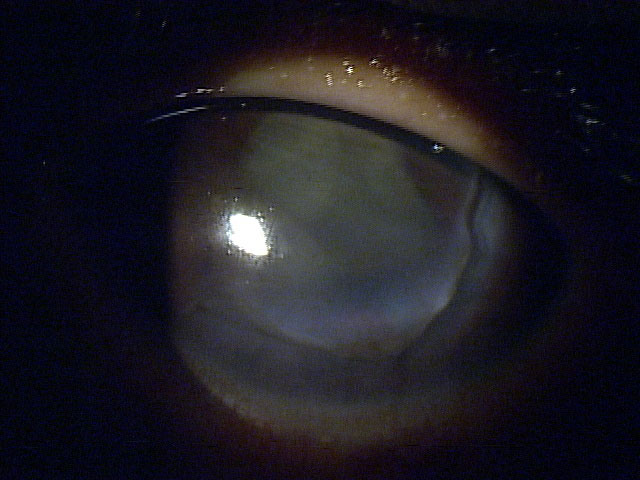

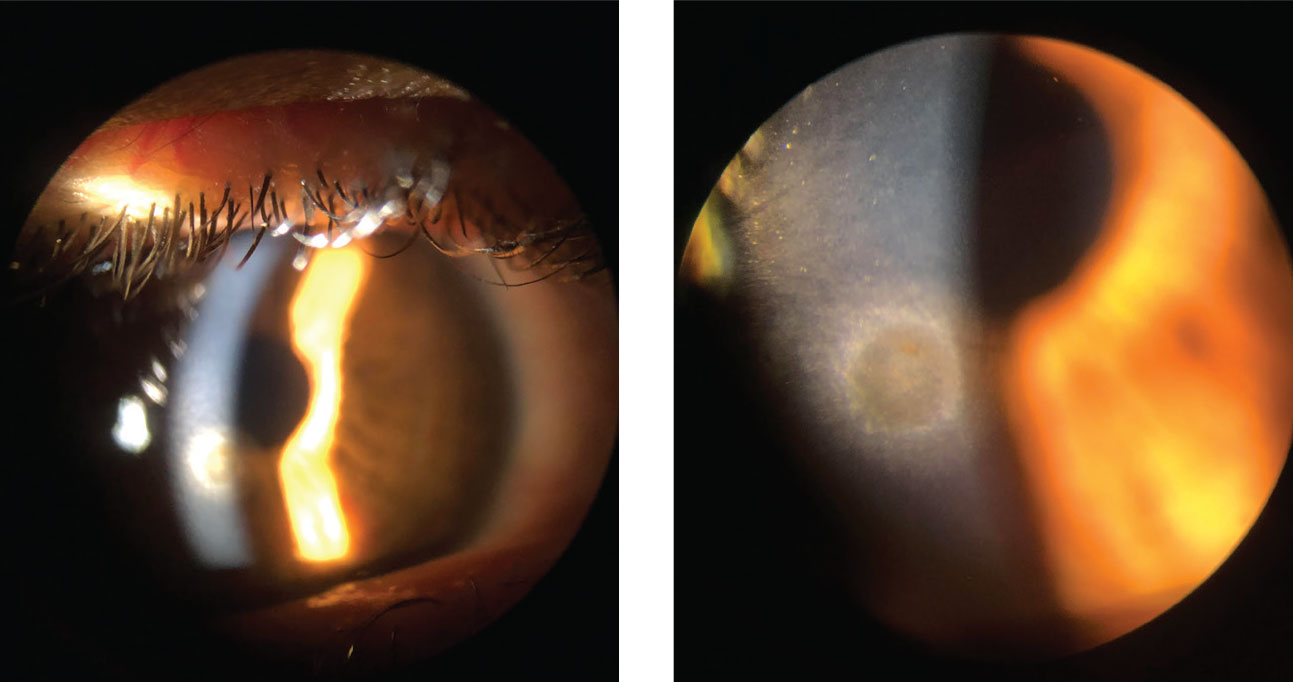

| Fig. 3. This 13-year-old boy was hit in the eye with his pencil in school, leaving a laceration from 2 o’clock to 9 o’clock. It was pressure patched and seen by cornea specialist, who glued the cornea until the patient could get into the surgical suite, where the surgeon placed 20 sutures to close up the wound. Click image to enlarge. |

Initial Encounter

When a patient calls or walks in complaining of a foreign body sensation, your front desk staff must understand what to ask the patient to triage and make sure they are seen or referred promptly. Front office and call center staff should begin the patient encounter, whether in person or on the phone, with the tried-and-true five Ws: who, what, where, when and why. These help to ensure patients who need urgent care get it, and those who don’t can be scheduled accordingly.

For example, a patient who calls saying something got in their eye while doing yardwork yesterday requires different treatment than a patient who had the same thing happen to them a month ago. The latter situation is far less urgent and is less likely a true foreign body than the patient who sustained an injury the day before.

Patients who mention additional injuries related to the incident may require further testing or treatment. Head trauma requiring imaging or sutures should be sent to the emergency room to address those injuries first. However, keep in mind that MRI is contraindicated for patients with a suspected metallic foreign body. With their serious injuries cared for, the patient can be seen back regarding the ocular foreign body if it wasn’t treated concurrently in the emergency room.

The five Ws can also help to correctly identify patients who may have had a work-related injury associated with a worker’s compensation case. These situations often require extra paperwork to document the details. During documentation, also note if the patient was wearing appropriate personal protective eyewear.

|

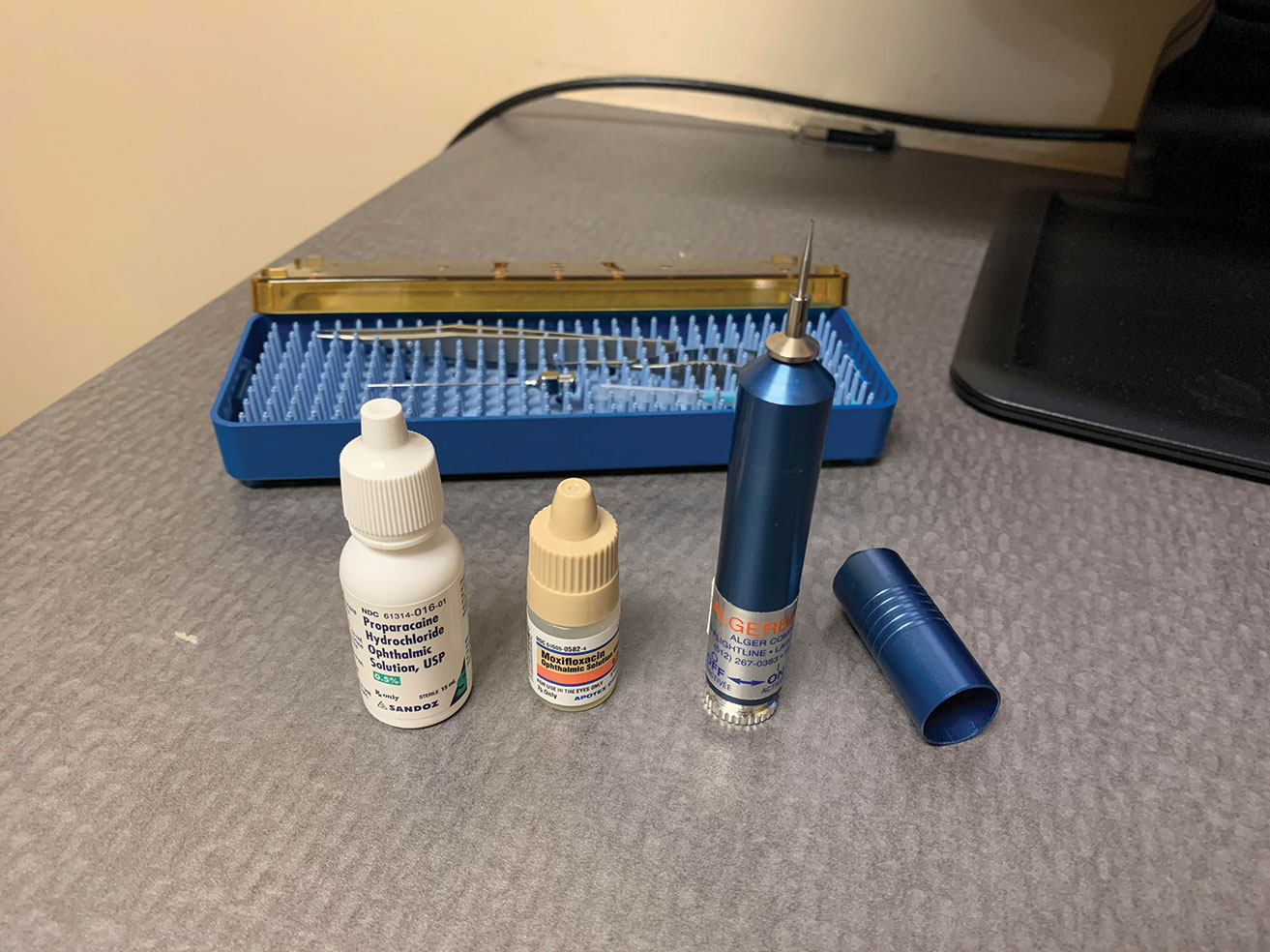

| Fig. 4. Here is what you will typically need when removing a corneal rust ring with an Alger brush: start with topical proparacaine along with a broad-spectrum topical antibiotic. After the procedure is complete, instill a second drop of antibiotic into the patient’s eye. Click image to enlarge. |

In the Chair

Once you are sitting down with the patient, have a detailed discussion with them to understand what exactly is in their eye and how it got there. Depending on the type of foreign body and the timeline, there may be a concern for secondary infections. Patients with suspected vegetative matter warrant higher concern for the development of a fungal corneal ulcer, while a metallic object could cause a rust ring or, more rarely, introduce infectious material leading to bacterial keratitis.

We also know that the longer the foreign body is in the eye and there is an open abrasion, the higher the risk of developing bacterial keratitis that could lead to an ulcer or even an anterior chamber reaction.2 A study of patients with corneal abrasions due to ocular foreign bodies found that no patients who were seen in clinic within 18 hours of the ocular injury and started on prophylactic antibiotic ointment developed an ulcer.2 However, of those who presented 19 to 24 hours after injury, 3.7% developed an ulcer and 28.6% of those seen between 24 and 48 hours after developed an ulcer.2

A thorough slit lamp exam will help you determine if the foreign body is still there, its location, depth within the ocular tissue and if it has fully penetrated the cornea (Figure 2). If available, anterior segment OCT can be useful in identifying the depth of the foreign body.3 Patients with a foreign body or abrasion are typically light sensitive and in pain. Instilling a drop of ocular topical anesthetic will help you perform the slit lamp exam.

Make sure to stain the patient’s eye with sodium fluorescein and use a cobalt blue filter to check for multiple vertical lines on the cornea (tracking patterns) or conjunctival abrasions that may indicate trapped foreign material under or within the lid. Also evert the patient’s lid to visualize all fornicies and ensure no trapped material is causing further corneal damage or later lodge itself within the cornea.

If the injury occurred from a high-velocity impact or while grinding, it is important to dilate to look for signs that the foreign body has fully penetrated the cornea or globe. Conjunctival penetration is easier to see because there will typically be an area of injection and chemosis surrounding the entrance point. When a conjunctival foreign body or full penetration of the cornea or globe is suspected, check the patient for a positive Seidel’s sign with sodium fluorescein and cobalt blue light filter. Another indication of full penetration with a wound leak would be decreased intraocular pressure or a shallow anterior chamber.

When looking at the entrance wound on the cornea, check for tracks or disrupted tissue through the cornea stroma or endothelium. An object that has penetrated the ocular lens typically leaves a mark on the anterior portion of the lens, possibly damaging the iris—a wound that can be viewed with iris transillumination.

Dilation aids in seeing these lenticular marks and helps us visualize the back of the eye to look for the retained object. If you suspect a penetrating intraocular foreign body but cannot directly visualize it, consider sending the patient for orbital radiographs, B-scan or computed tomography to identify and pinpoint the object.4 However, this is not mandatory and may not be a practical use of resources in all cases.

|

| Fig. 5. When removing the rust ring from the cornea with the Alger brush, make sure to approach tangentially. This allows for better control of the instrument and pressure applied to the cornea. Click image to enlarge. |

Removal Step-by-step

While most of us learned how to remove a foreign body during our education, its rarely an everyday occurrence. Many regional and national conferences provide workshops to help those who feel the need for new or additional training. Before performing any procedure, consult your state law and scope of practice to make sure that you are practicing within your guidelines.

Before you begin, discuss the steps of the procedure with the patients to reduce their anxiety. In addition, obtain written consent or document in the chart that the patient verbally consented to the treatment plan. If a patient has poor cooperation or is struggling to keep their eyelids open, a lid speculum can help. Have the patient fixate on a target with the opposite eye to help the eye still. Instill a topical anesthetic and a broad-spectrum topical antibiotic.

The location and type of foreign body will often determine how you remove them. Most of us have a preferred method and instrument that we feel comfortable using to remove foreign bodies.

Superficial or loosely embedded corneal foreign bodies are often easily removed with a sterile cotton swab, spud or a small-gauge needle.

If the foreign body is deeper within the corneal stroma, use a spud or 25-gauge needle. Using the patients’ forehead for stability, hold the needle head tangentially to the cornea with the beveled tip up, away from the cornea. Place the tip underneath the anterior projection of the foreign body and carefully tease it out. Once dislodged from the stroma, the object can be removed from the surface with a cotton swab or forceps.

Depending on the practitioner’s comfort level, they should consider referring patients to a cornea specialist. In cases where there is full globe or corneal penetration or a concern for vision-threatening scarring, it is advantageous to consult with a cornea specialist regarding any further treatment or surgical procedures to reduce scarring (i.e., lamellar keratectomy).

Depending on the angle and size of the foreign body, jeweler’s forceps are helpful in cases where the object is protruding from the cornea where an edge is easily accessible or when the foreign body is small such as a splinter or fiberglass.

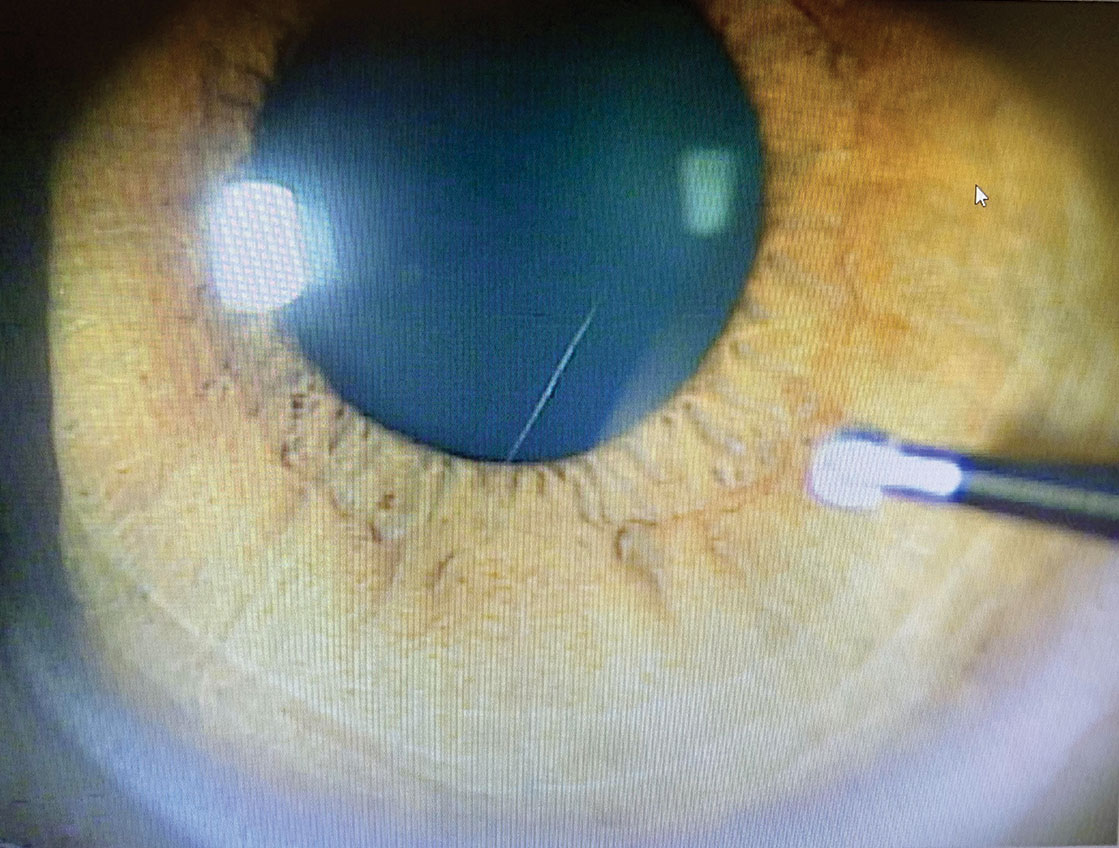

|

| Figs. 6 and 7. This patient is being seen at follow-up after a metallic foreign body was removed. While the epithelium has fully healed, there is a remaining rust ring. Click image to enlarge. |

If, during the slit lamp and dilation or with anterior segment OCT, you determine the foreign body is full penetrating, consult a surgeon for treatment and removal. If the patient has a positive Seidel’s sign or suspected open laceration, give them a drop of topical antibiotic, pressure patch them to reduce the flow of the leaking aqueous and refer immediately (Figure 3).

Metallic foreign bodies containing iron may leave behind a rust ring in as little as three to four hours.5 In the event that a rust ring forms, removal is performed using an Alger brush (Figure 4). Use a clean sterile tip and approach the area tangentially with the brush to better control the tool (Figure 5). Any remaining rust ring could cause inflammation and slow or even prevent healing of the corneal epithelial defect. When the rust is deep within the stroma, the patient may require a second treatment with the Alger brush during the follow-up visit to remove the entire rust ring (Figures 6 and 7). However, it is better to remove the entire ring on the initial visit, whenever possible, to reduce the necessity of retreatment.

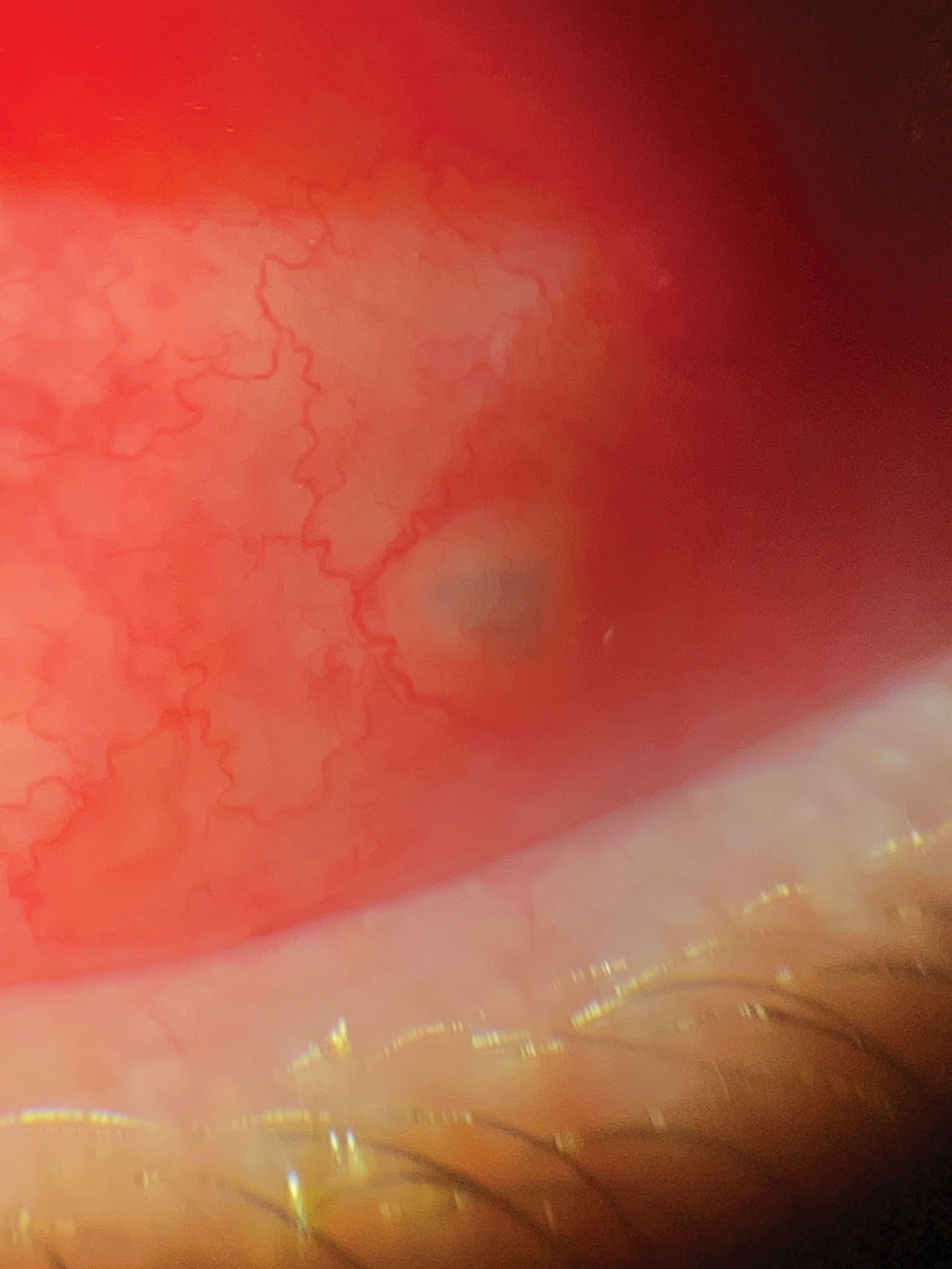

When the foreign body seats itself within the conjunctiva, clinicians may be able to remove it in-office without surgery (Figure 8). The entering wound, if shallow and recent, sometimes functions as an access point for removal with jeweler’s forceps. If it has been more than 48 hours or the material is seated too deeply, the removal may require incision and possible sutures and, in some cases, may warrant a referral.

Bacterial cultures are not routinely performed on patients with corneal foreign bodies without a stromal infiltrate. One study found that only nine of 63 tested corneal foreign bodies were positive for bacteria.6

After any foreign body removal, scan the patient’s eye to ensure no other possible foreign bodies are present and document the extent of the patient’s treatment area.

Most importantly, educate the patient prior to leaving the office regarding proper protective eye wear to help decrease the likelihood of re-occurrence. Discuss not only what is considered proper protective eye wear but also when they should be wearing it (e.g., yard work, working on cars, grinding, cutting).

|

| Fig. 8. This patient presented to the office within eight hours of being hit in the eye with a tree branch. A piece of bark had lodged itself under the conjunctiva. The foreign body was removed with forceps through the entry point with no sutures needed. Click image to enlarge. |

Homework

Patients should be started on a topical antibiotic immediately following the removal of the foreign body. Typically, a broad-spectrum topical antibiotic drop such as a flouroquinolone QID is appropriate, given the patient has no allergies. In the case of conjunctival involvement or large abrasions, the patient may be more comfortable using an ophthalmic antibiotic ointment such as tobramycin or Polytrim (polymyxin B/trimethoprim, Allergan) BID to QID. If vegetative matter involvement is suspected and a fungal ulcer is present, the patient should be started on topical and oral anti-fungal medication.

Pain management for these patients can vary depending on situation and the patient. The use of a therapeutic bandage contact lens, while not necessary, can provide sufficient relief but should be avoided if there is any formation of secondary ulcer at the time of exam. Some patients find comfort from pressure patching the eye, although this can be cumbersome with the requirement of frequent ocular drops. To avoid this, it is preferable to use ophthalmic antibiotic ointment, instilled prior to pressure patching. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents can aid in pain management, as can atropine.

Oral analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications such as Tylenol and ibuprofen may be added as needed. The use of narcotics can be considered on a case-by-case basis in appropriate patients but is often unnecessary.

Patients with larger lesions and those with a bandage contact lens or pressure patch should have a follow up in 24 hours. Smaller or peripheral lesions can have an extended follow up of up to a week for non-complicated cases if no ulcer or infection is present. When an ulcer has formed or infection is present, the patient should be seen the next day to monitor for improvement.

Amniotic membranes or amniotic drops can also be considered for patients with deep central foreign bodies.7 If the patient’s injury was due to vegetative matter, it is important to watch for possible infiltrate and ulcer development prior to starting any steroid, as this will worsen a fungal infection.

Knowing how to help established or new patients with an urgent foreign body situation is essential for your community and your practice. The need for foreign body removal is a common and frequent complaint. As optometrists, we should feel comfortable in treating, or in the very least, triaging these patients. Once you establish yourself as knowledgeable and competent, you will enjoy increased personal fulfillment—and referrals.

Dr. Koetting is the referral optometric care and externship program coordinator at Virginia Eye Consultants in Norfolk, VA. She is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and a trustee of the Virginia Optometric Association.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Eye safety. www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/eye. September 30, 2010. Accessed March 9, 2020. 2. Upadhyay MP, Karmacharya P, Koirala K, et al. The Bhaktapur eye study: ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(4):388-92. 3. Wylegala E, Dobrowolski D, NowiDska A, Tarnawska D. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography in eye injuries. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247(4):451-5. 4. Brightbill F, McDonnell P, McGhee C, et al. Corneal Surgery: Theory, Technique and Tissue. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009. 5. DeBroff B, Donahue SP, Caputo BJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of corneal foreign bodies and their associated culture results. CLAO. 1994;10(2):128-30. 6. Bartlett JD, Jaanus SD. Clinical Ocular Pharmacology. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007. 7. Shelter J, Lighthizer N. Foreign body removal in 12 steps. Rev Optom. 2015;152(1):22-29. |