|

A better understanding of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) has been key to our ability to more effectively manage dry eye disease in the last decade.1

When I started my first dedicated dry eye clinic, it wasn’t identified regularly, and perhaps that is why patients weren’t achieving high success with their dry eye disease management. And even if we knew to look for and grade MGD, few effective treatments existed then. Screening for and uncovering the presence of MGD in patients, looking at the components of the disease and then choosing effective treatments are integral to today’s success in the management of this common cause of dry eye disease.

MGD can result in significant and progressive dry eye disease that can, in turn, lead to severe atrophy of the meibomian glands. It also may be a leading cause of contact lens dropout, whether by affecting blink rates or adding stress to the required meibomian gland output.2,3

If clinicians are not looking for MGD and associated complications, they can’t take measures to prevent patients from abandoning contact lens use or seeking another eye doctor. MGD can contribute to inaccurate biometry measurements for IOL calculations and unexpected outcomes following refractive surgery.

Identifying MGD

Every exam should include a close look at the meibomian glands and their expression characteristics. When examining the lower eyelid in particular—which is responsible for the majority of oil in the tear film—look for notching, which is a sign of gland atrophy; froth in the tear film, which is an indication of meibomian gland dysfunction; telangiectasia; tylosis or thickening of the eyelids; and hyperemia. Next, use a wet cotton-tip applicator, the Meibomian Gland Evaluator (TearScience) or an expression paddle such as the Mastrota Paddle (OcuSoft) to express the area of the nasal to central lower eyelid glands. Note how many glands express and the quality of the meibum. Healthy meibum is clear like olive oil and easily expresses, barely noticeable when rolling off the eyelid. A turbid expression or paste-like or non-expressive glands are indicative of further progression of the disease.4

| |

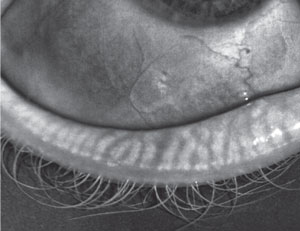

| A 28-year-old female patient showing early signs of MGD. |

Other tests that help with a diagnosis include osmolarity testing, patient questionnaires such as the SPEED or OSDI questionnaire, blink analysis and especially meibography. Meibography can reveal the effects on the structure of the gland and show areas of atrophy, aiding in the diagnosis and severity of the disease.5

MGD Components and Effective Management

Although the mechanism underlying MGD is likely multifactorial and complex ranging from androgen deficiency to evaporative stress and low humidity environments, MGD itself begins with obstruction of the meibomian glands that leads to further sequelae which may need to be managed.6,7 Although not every case has all four components, the other sequelae include inflammation, biofilm development and tear film disruption or instability.8 Here are each of the four components and their respective treatment options:

Obstruction. When obstruction occurs, it may cause the other glands to up-regulate or over-work to make up for the ones that are not functioning. This leads to further stress and, eventually, gland atrophy. If a gland is dysfunctional for a period of time, it may also get a keratin covering that further prevents its ability to produce oils for the tear film.9

While treatment options may include scaling the lower eyelid to remove keratin, the key to obstruction removal is thermal treatments that can soften the meibum over time and promote proper gland expression. One technology that combines both is the LipiFlow thermal-pulsation system (TearScience). You can get a significant effect in a relatively short treatment time by avoiding the external eyelid and instead providing heat through the back surface of the eyelid.10 Adding pulsation may further improve the meibum consistency. Other thermal systems that may benefit patients with MGD obstruction include MiboFlo (Mibo Medical Group) and intense pulsed light (IPL) devices. Studies also show potential for infrared heat treatments.11

| |

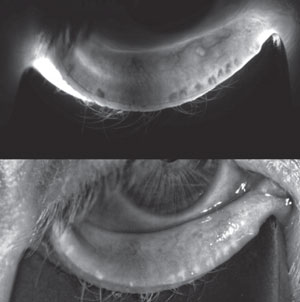

| A 56-year-old female with endstage MGD manifesting significant gland atrophy/drop out. |

Keep in mind that previous MGD treatments such as ‘rice-in-a-sock’ simply do not allow adequate penetration of heat because of the limits through the external skin. There are also limitations to a wet washcloth compress, as patients must exchange the washcloths while at a sink for eight to 10 minutes or longer to maintain adequate heat levels. But warm compresses increase the tear film lipid layer if penetrating heat and compliance is in place.12,13 A new daily compress, the Bruder Eye Hydrating Compress (Bruder Healthcare Company), uses unique beads with a small angstrom opening that, upon microwaving for 15 to 20 seconds, releases hydration that is obtained from the environment. It is reusable, durable, can be washed and provides adequate heat and hydration for approximately 12 to 14 minutes. The hydration aids in transfer of heat to the glands. Other commercial compresses include ThermoEyes (OcuSoft), TheraPearls (Bausch + Lomb) and TranquilEyes (Eye Eco). Note that patients are no longer instructed to massage their eyelids after using compresses, due to potential changes to the cornea and because thermal pulsation systems are now used for that purpose.14

Inflammation. Studies show that inflammation can be present in cases of both MGD (meibomitis) and dry eye disease.15 Inflammation plays a key role in further damage and progression of both diseases because of the constant stress of a poor tear film, friction from the eyelid moving across the ocular surface and obstruction of glands; thus, it is crucial to treat the inflammation. Anti-inflammatory medications known to work include cyclosporine, corticosteroids and corticosteroid-combination agents, oral doxycycline, topical azithromcyin and oral azithromycin and omega fatty acids.15-21

Biofilm Formation. Lid hygiene may also play a role in the management of MGD, as biofilms have been known to develop in this disease. A biofilm is an aggregate of bacterial microorganisms that coat a particular living or non-living structure. Biofilms can cause infections or affect structural physiology and may actually become more resistant to treatment than individual bacterial colonies not in a biofilm formation.22 Studies show that repetitive lid hygiene products such as eyelid cleansers and mechanical cleaning devices such as BlephEx (BlephEx) help minimize the negative effects of biofilms.23-25

Tear Film Instability. Without an adequate lipid component to the tear film, evaporation ensues. Evaporation causes increased meibocyte production that is greater than the oil production, further obstructing the glands and increasing tear film instability.26 Patients with tear film alterations have dry eye and require artificial tears to supplement the tear film. Cyclosporine is a possible treatment option for tear film instability.

MGD is a critical disease that results in chronic dry eye, and the progression of the disease ultimately results in complete MG atrophy. It likely plays a key role in contact lens drop out, unexpected postsurgical complications and overall quality of vision. By looking at the components of the disease—including obstruction, inflammation, biofilm formation and tear film instability—clinicians can effectively manage and provide patients with adequate treatment, symptomatic relief and an improved quality of life.26

Dr. Karpecki has a financial relationship with AcuFocus, AMO, Alcon Labs, Allergan, Akorn, Bausch + Lomb/Valeant, BioTissue, Bruder Healthcare, Cambium Pharmaceuticals, Eleven Biotherapeutics, Eyemaginations, Essilor, Fera Pharmaceuticals, Focus Laboratories, iCare USA, Ocusoft, Freedom Meditech, Konan Medical, Beaver-Visitech, Eye Solutions, Reichert, Shire Pharmaceuticals, RySurg, Science Based Health, SightRisk, TearLab, TearScience, TLC Vision, Topcon and Vmax.

1. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey- based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009;7(2 suppl):S1-14.2. Foulks GN, Borchman D. Meibomian gland dysfunction: the past, present, and future. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(5):249-53.

3. Jansen ME, Begley CG, Himebaugh NH. Effect of contact lens wear and a near task on tear film break-up. Optom Vis Sci. 2010 May;87(5):350-7.

4. Hom MM, Silverman MW. Displacement technique and meibomian gland expression. J Am Optom Assoc. 1987 Mar;58(3):223-6.

5. Srinivasan S, Menzies K, Sorbara L, et al. Infrared imaging of meibomian gland structure using a novel keratograph. Optom Vis Sci. 2012 May;89(5):788-94.

6. Sullivan DA, Sullivan BD, Evans JE, et al. Androgen deficiency, meibomian gland dysfunction and evaporative dry eye. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999 June;876:312-24.

7. Suhalim JL, Parfitt GJ, Xie Y, et al. Effect of desiccating stress on mouse meibomian gland function. Ocul Surf. 2014 Jan;12(1):59-68.

8. Pflugfelder SC, Karpecki PM, Perez VL. Treatment of blepharitis: recent clinical trials. The Ocular Surface. 2014 October;12(4).

9. Ong BL, HOdson SA, Wigham T, et al. Evidence for keratin proteins in normal and abnormal human meibomian fluids. Curr Eye Res. 1991 Dec;10(12):1113-9.

10. Finis D, Hayajneh J, König C, et al. Evaluation of an automated thermodynamic treatment (LipiFlow) system for meibomian gland dysfunction: a prospective, randomized, observer-masked trial. Ocul Surf. 2014 Apr;12(2):146-54.

11. Goto E, Monden Y, Takano Y, et al. Treatment of non-inflamed obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction by an infrared warm compression device. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002.

12. Olson MC, Korb DR, Greiner JV. Increase in tear film lipid layer thickness following treatment with warm compresses in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. Eye Contact Lens. 2003 Apr;29(2):96-9.

13. Romero JM, Biser SA, Perry HD, et al. Conservative treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Eye Contact Lens. 2004 Jan;30(1):14-9.

14. McMonnies CW, Korb DR, Blackie CA. The role of heat in rubbing and massage-related corneal deformation. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2012 Aug;35(4):148-54.

15. Suzuki T, Teramukai S, Konoshita S. Meibomian glands and ocular surface inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2015 Apr;13(2):133-49.

16. Prabhasawat P, Tesavibul N, Mahawong W. A randomized double-masked study of 0.05% cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2012 Dec;31(12):1386-93.

17. Chen M, Gong L, Sun X, et al. A multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of loteprednol etabonate 0.5%/tobramycin 0.3% with dexamethasone 0.1%/tobramycin 0.3% in the treatment of Chinese patients with blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:385-94.

18. White EM, Macy JI, Bateman KM, Comstock TL. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of loteprednol 0.5%/tobramycin 0.3% with dexamethasone 0.1%/tobramycin 0.3% in the treatment of blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:287-96.

19. Foulks GN, Borchman D, Tappert M, et al. Topical azithromyci and oral doxycycline therapy of meibomian gland dysfunction: a comparative clinical and spectroscopic pilot study. Cornea. 2013 Jan;32(1):44-53.

20. Kashkouli MB, Fazel AJ, Kiavash V, et al. Oral azithromycin versus doxycycline in meibomian gland dysfunction: a randomized double-masked open-label clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb;99(2):199-204.

21. Oleñik A, Mahillo-Fernández I, Alejandre-Alba N, et al. Benefits of omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplementation on health-related quality of life in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr;30(8):831-6.

22. Sanclement J, Webster P, Thomas J, et al. Bacterial biofilms in surgical specimens of patients with chronic rhinosiunusitis. Laryngoscope. 2005 Apr;115(4):578-82.

23. Guillon M, Maissa C, Wong S. Eyelid margin modification associated with eyelid hygiene in anterior blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. Eye Contact Lens. 2012 Sep;38(5):319-25.

24. Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;16:5.

25. Guillon M, Maissa C, Wong S. Symptomatic relief associated with eyelid hygiene in anterior blepharitis and MGD. Eye Contact Lens. 2012 Sep;38(5):306-12.

26. Suhalim JL, Parfitt GJ, Xie Y, et al. Effect of desiccating stress on mouse meibomian gland function. Ocul Surf. 2014 Jan;12(1):59-68.

27. Paugh JR, Knapp LL, Martinson JR, Hom MM. Meibomian therapy in problematic contact lens wear. Optom Vis Sci. 1990 Nov;67(11):803-6.