|

Keratitis is a rather nonspecific term and one we should try to move away from in pursuit of greater specificity, as inflammation of the cornea can be caused by injuries, infection by numerous organisms, countless diseases and even contact lens overwear. Though often mild and temporary, some types can be severe and ultimately lead to permanent vision loss. Fungal keratitis (FK) is a challenging diagnosis, and if its identification and treatment are delayed or incorrect, the sequelae can be irreversible. Practitioners should maintain a high level of clinical suspicion in these cases and know how to safely and effectively manage cases of FK.

Causes

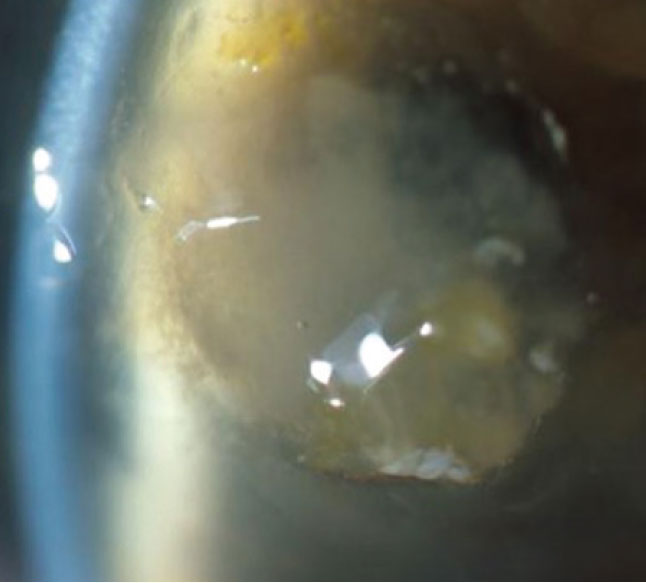

Infectious or microbial keratitis can be due to bacteria, viruses (e.g., HSV), protozoa (most notably Acanthamoeba) or fungi. It has been reported that FK is more virulent and damaging than bacterial disease.1 Trauma is a major factor for FK in developing countries and is often accompanied by a microorganism invasion that leads to corneal surface changes and immune-mediated inflammation, causing tissue necrosis. The deeper fungi penetrate in the stroma, the more extensive tissue damage, scarring and corneal opacification become. Early diagnosis and treatment are imperative to avoid sight-threatening complications.

The most common fungi in keratitis are filamentous, such as Fusarium and Aspergillus, or yeast-like fungi, such as Candida. The prevalence of specific agents is directly related to geography, and FK often occurs in tropical and subtropical regions.

In the United States, 30,000 new cases are reported annually with Candida and Aspergillus being the most common causes.2 Fusarium is more common in southern states such as Florida.3,4 There has also been a general increase in filamentous FK cases in contact lens wearers.5,6

|

|

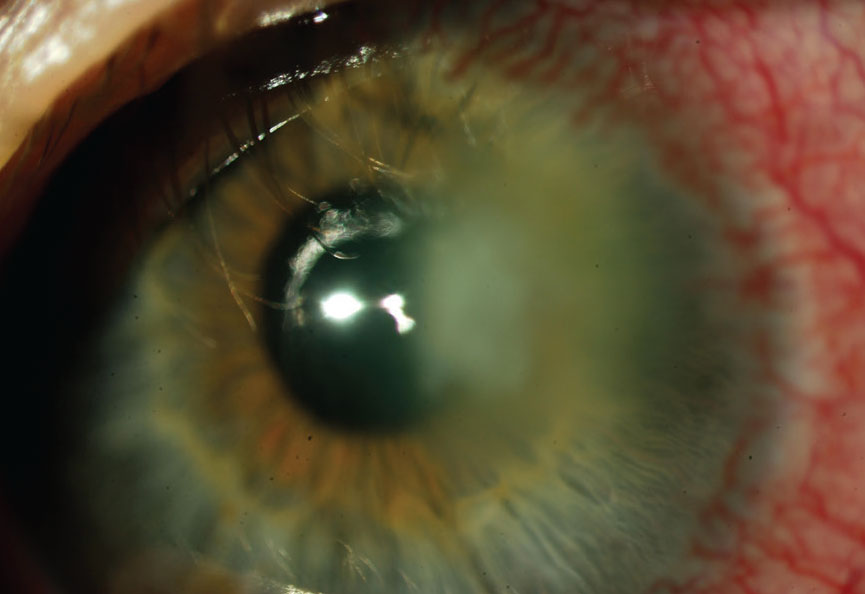

Take note of any anterior chamber reaction, which can occur in the presentation of FK. Click image to enlarge. |

Presentation

Patients with keratitis will report a sudden onset of pain, photophobia, discharge and reduced vision with an inflamed, hyperemic eye and an opacity suggestive of an ulcer. In trauma involving vegetative matter or in contact lens wearers, practitioners should have a high degree of suspicion. Corneal ulcers that do not respond to broad-spectrum antibiotics, centrally located infiltrates and/or the presence of satellite lesions are signs that should raise a red flag to the possibility of a mycotic agent.

Due to the challenges in making the differential diagnosis based on traditional features, cultures may be necessary in suspected FK. I consider the one-two-three rule when determining the need for a culture or comanagement with a cornea specialist: if the ulcer is 1mm from the visual axis, if there are two or more infiltrates (satellite lesions or multiple infiltrates are an indication of fungal causes) and if an infiltrate 3mm or larger is present.

|

|

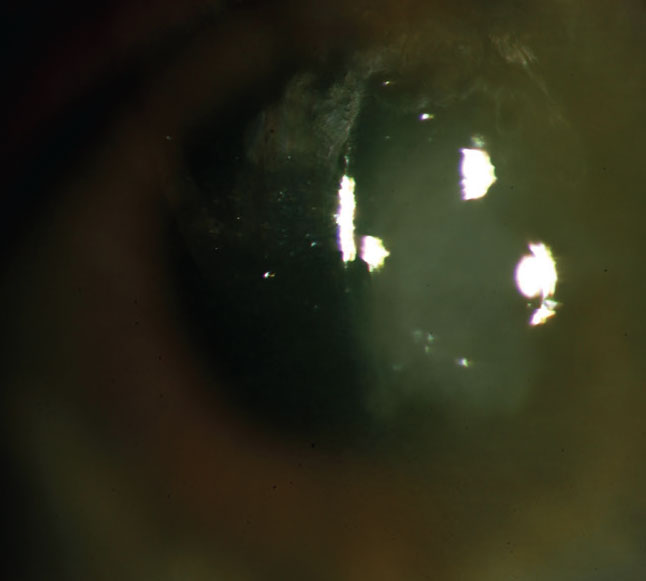

FK can lead to corneal scarring, glaucoma and endophthalmitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Slit Lamp Exam

Look for evidence of ocular surface disease, determine the amount and type of secretions and assess lid swelling. The upper eyelid should be everted to ensure there is no retained foreign body. The size and depth of the lesion as well as the presence of satellite lesions should be ascertained. Note any anterior chamber reaction and especially evidence of hypopyon, which can occur in an FK presentation. If there is a vitreous reaction, intraocular spread of the disease may be likely.

Under the slit lamp, a lesion might be similar in appearance to an unhealed corneal abrasion with scant infiltrates and no discharge. Over time, an FK ulcer will develop thicker infiltrates and fuzzy margins. Redness and periocular edema are also common and combined with a history of trauma, especially with vegetable matter, ocular surface disease or chronic use of topical steroids, should alert the practitioner

|

|

FK may be more virulent and damaging than bacterial disease. Click image to enlarge. |

to the possibility of a mycotic etiology.

Treatment

It is crucial to avoid steroids (including combination antibiotic/steroid agents) until the true etiology is determined. In the meantime, patients can be started on a strong fluoroquinolone, and if there is a central lesion, alternate with a fortified antibiotic—ideally vancomycin.

In a contact lens wearer, where Pseudomonas is a possibility, I favor fortified tobramycin; otherwise, fortified vancomycin. Continue this regimen every hour on the first day depending on severity. Cycloplegics can be added when there is significant pain. The reason for beginning with an antibacterial, even in suspicious cases, is because most MK looks similar in initial presentation and the vast majority is bacterial.

If the culture indicates FK, natamycin (Natacyn, Eyevance Pharmaceuticals) is the first-line treatment. Natacyn is the first antifungal agent approved for FK and is considered the most effective medication against Fusarium and Aspergillus, binding preferentially to ergosterol on the fungal plasma membrane.7,8

Prior to the development of natamycin, the most commonly used antifungal was amphotericin B, a polyene; it is still used alone and in combination with natamycin with relatively good results. Voriconazole, a triazole antifungal agent derived from fluconazole, can be used either topically at 1% dilution or orally at 400mg twice a day and has been injected in the corneal stroma around the fungal lesion.9

A newer-generation oral triazole, posaconazole, has been successful in eradicating deep infections of resistant Fusarium.10 Because subconjunctival antifungals can cause severe pain and potentially induce tissue necrosis, they are no longer used.

|

|

Early diagnosis and treatment of FK are critical to avoid complications. Click image to enlarge. |

Disease Course

The response in these patients is slow, with improvement seen in about three to six weeks. Continuing with the cycloplegic will help with pain and discomfort. Ibuprofen and/or acetaminophen can be added as necessary. Follow-up is daily until the epithelium closes, and once stable, patients can be seen weekly.

FK can lead to corneal scarring, corneal perforation, anterior segment disruption, glaucoma and even endophthalmitis, the latter potentially resulting in evisceration if it cannot be contained. There is severe visual loss in 26% to 63% of patients, and 15% to 20% may require evisceration. Penetrating keratoplasty is required in 31% to 38% of cases.11,12 Because it can be a catastrophic disease, FK must be differentiated from other corneal conditions with similar presentation; especially its bacterial counterpart, which accounts for the majority of microbial corneal infections.

In my experience, numerous cases of FK are not diagnosed in a timely fashion, leading to irreversible damage, and it’s important to obtain an accurate diagnosis and administer effective management.

Dr. Karpecki is medical director for Keplr Vision and the Dry Eye Institutes of Kentucky and Indiana. He is the Chief Clinical Editor for Review of Optometry and chairman of the affiliated New Technologies & Treatments conferences. A fixture in optometric clinical education, he provides consulting services to a wide array of ophthalmic clients. Dr. Karpecki’s full disclosure list can be found here.

| 1. Ansari Z, Miller D, Galor A. Current thoughts in fungal keratitis: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2013;7(3):209-18. 2. Pepose JS, Wilhelmus KR. Divergent approaches to the management of corneal ulcers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:630-2 3. Jones DB, Sexton R, Rebell G. Mycotic keratitis in South Florida: a review of thirty-nine cases. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1970;89:781-97. 4. Rosa RH, Jr, Miller D, Alfonso EC. The changing spectrum of fungal keratitis in south Florida. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1005-13. 5. Bullock JD, Elder BL, Khamis HJ, Warwar RE. Effects of time, temperature, and storage container on the growth of Fusarium species: implications for the worldwide Fusarium keratitis epidemic of 2004–2006. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:133-6. 6. Gower EW, Keay LJ, Oechsler RA, et al. Trends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2263-7. 7. Natamycin approved--first U.S. drug for fungal keratitis. FDA Drug Bull. 1978;8:37-8. 8. Medoff G, Kobayashi GS. Strategies in the treatment of systemic fungal infections. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:145-55. 9. Sharma N; Goel M; Titiyal JS; Vajpayee RB Evaluation of intrastromal injection of voriconazole as a therapeutic adjunctive for the management of deep recalcitrant fungal keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(1):56-9. 10. Tu EY, McCartney DL, Beatty RF, et al. Successful treatment of resistant ocular fusariosis with posaconazole (SCH-56592). Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:222-7. 11. AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 8: External Disease and Cornea, 2015-2016. 12. Rondeau N, Bourcier T, Chaumeil C, et al. Fungal keratitis at the Centre Hospitalier National d’Ophtalmologie des Quinze-Vingts: retrospective study of 19 cases. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2002;25(9):890-6. |