Optometry Today and TomorrowFollow the links below to read the other articles: Will Online Refraction Tarnish Telemedicine? |

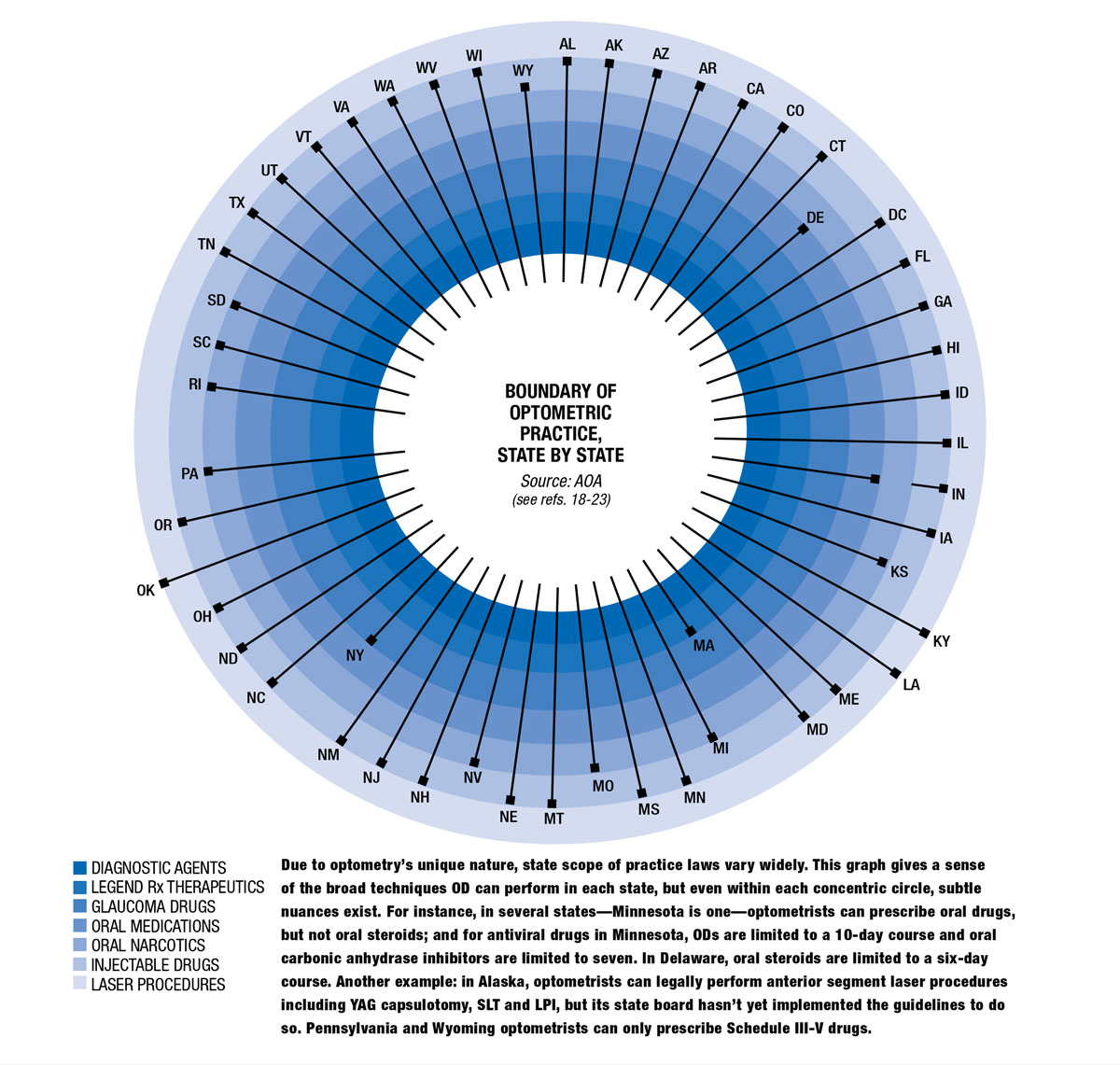

"Optometry is a legislated profession” is a refrain ODs hear over and over throughout their education and into their careers. The entire scope of practice is dependent on the passage of statewide bills. As a result, optometry has become 50 slightly different professions throughout the country, with 50 different menus of procedures and indications available. These variations are decided by lawmakers, but often reflect the whims of a powerful medical lobby that pushes skepticism about optometry.

That means optometrists who consider employment opportunities across state lines need to consider what optometry will even mean in their new home. This is a quandary unique to optometry. Doctors of other stripes, once licensed, are free to operate comparatively uninhibited. A DO or an MD in Oregon has the same rights as one in Florida.

However, due to a perfect storm of economics, demographics, education and technology, optometry is primed to look a lot more like traditional medical practice, if it can finally face down an age-old rivalry (see Eight Decades of Chicanery, p. 36).

“The whole concept of optometrists moving from a nontherapeutic profession to a therapeutic profession has taken a decade or two, but it’s slowly, steadily still catching on,” says Randall Thomas, OD, of Concord, NC.

|

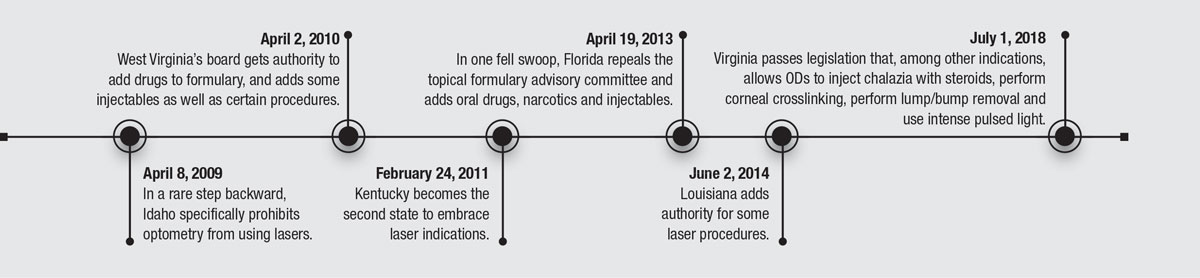

| Click image to enlarge. |

From the Front Lines

Oklahoma is rounding out its second decade with lasers, Kentucky is approaching its 10-year anniversary and Louisiana enters year five. This gives the profession’s advocates a prized resource: empirical data. Optometric groups are using this track record to show that ODs can provide safe and effective treatments with lasers. “We’re going to have very good data to show that we’re not blinding people and patients are getting improved access to care, so as each state looks at the data moving forward, it’ll be hard for ophthalmology to object,” says Richard Mangan, OD, of Aurora, CO.

Organized optometry has seen a number of successes lately, both in scope expansion and legislation to protect optometrists and their patients.

In recent years, Florida, Missouri, West Virginia and Colorado are among several states that have taken on noncovered services legislation.1 While these measures lay the groundwork for scope expansion by elevating the profession, legislative changes are being seen in other states such as Virginia, California and Alaska.

It’s all part of the American Optometric Association’s (AOA) and its state affiliates’ strategy, which is less focused on individual indications and more on “making sure the state boards of optometry have the authority to regulate the profession,” says Samuel Pierce, OD, president of the AOA. “That’s important, because you want the state boards to determine what is and isn’t allowed for an OD, and you want a state law that supports the profession by allowing doctors to incorporate new technologies into their practice rather than go back and ask permission time and again.”

California, under its Optometry Practice Act, did just that by allowing ODs to completely restructure their regulatory system.2 Now, any non-controlled medication, device or technology that is FDA approved for an eye condition that optometrists treat is automatically approved for optometry.2 Similarly, off-label medications, devices and technologies need only be approved by California’s licensing board. Before this expansion, ODs also weren’t permitted to administer flu or shingles vaccinations. Now, they can.

But sometimes listing specific procedures has worked too, as was the case this year in Virginia when legislation enacted on July 1 included the right to perform corneal crosslinking, intense pulsed light and chalazian injections with steroids, as well as six other lump and bump removal techniques, explains Dr. Pierce.

In Alaska, the board of examiners in optometry will soon have the authority to write regulations allowing ODs to practice to the highest level of their education.3 That will almost certainly include YAG capsulotomy, SLT and laser peripheral iridotomy as well as foreign body and lump-and-bump removal. However, “just because you pass a law doesn’t mean everybody can start doing it,” explains Dr. Pierce. “The state board has to create a regulatory process.” Once Alaska irons out those last few kinks, they’re likely to become the fourth laser state in the nation.

Optometry is making inroads anywhere that seems amenable to its growth. At the top of that list, it seems, are states neighboring those with the most indications. It’s a reasonable strategy. If a patient lives close enough to the border of Louisiana or Oklahoma—say, perhaps, in Arkansas, which borders both—nothing is stopping them from getting the procedure done across state lines by an optometrist rather than an in-state ophthalmologist.

Lawmakers may even be convinced from a business standpoint, explains one scope expansion advocate. If they think optometrists are likely to pack up shop and move to where they can practice to the fullest extent of their education, they may not want to be responsible for a dearth of primary eye care providers. As such, those southeastern states are inching ever closer to passing OD-friendly bills. Just take a look at Florida, where, last year, news of a bill merely passing a subcommittee vote spooked organized medicine enough to warrant a media campaign against it.4 That bill ultimately died in another subcommittee.5 But it represents progress.

In nearby North Carolina, a group called North Carolina Citizens for Clear Action targeted a particular state legislator who co-sponsored a scope expansion bill, funneling at least $100,000 to confront the state senator with flyers, mailers and television ads.6,7 The three-term incumbent—David Curtis, OD—lost his May primary and resigned in June.7,8 Local reporting shows that the group North Carolina Citizens for Clear Action was funded by another group: the North Carolina Society of Eye Physicians and Surgeons.6

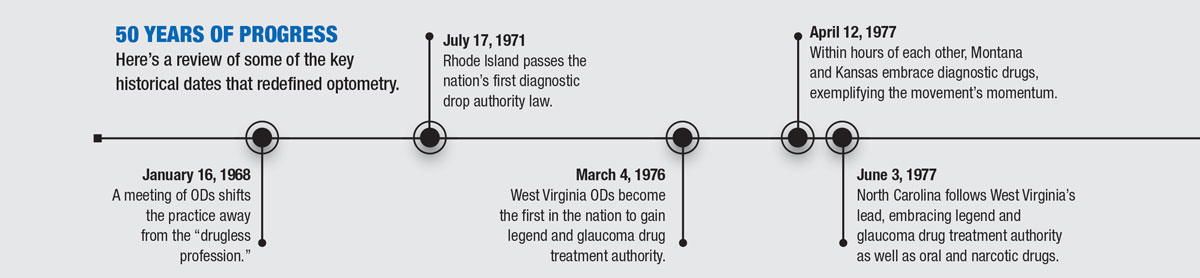

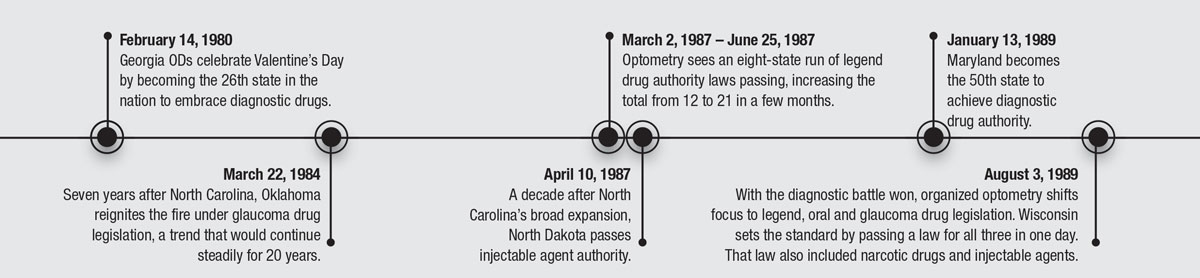

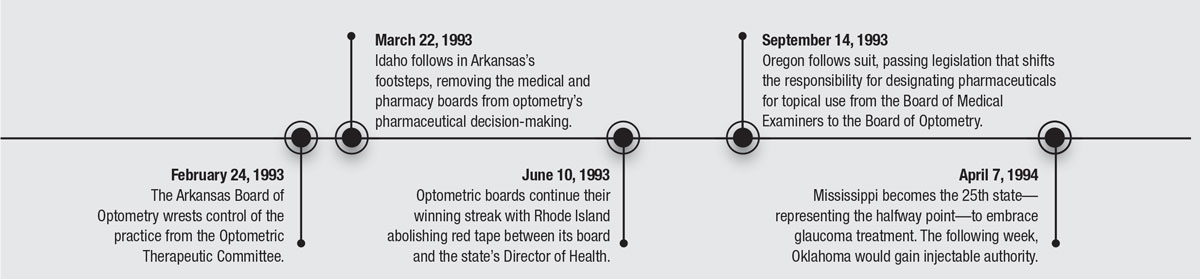

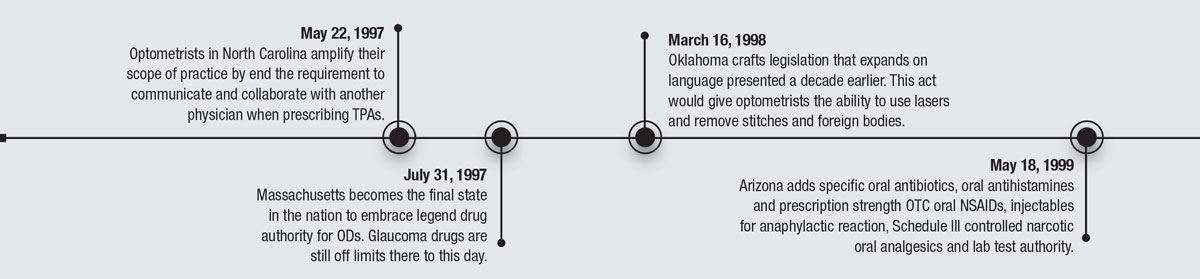

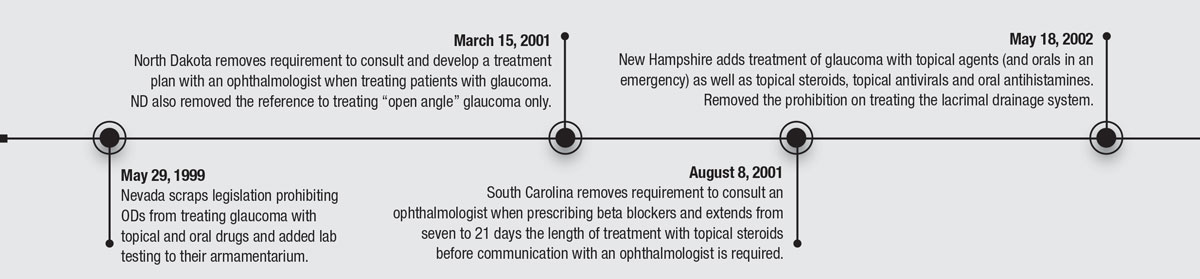

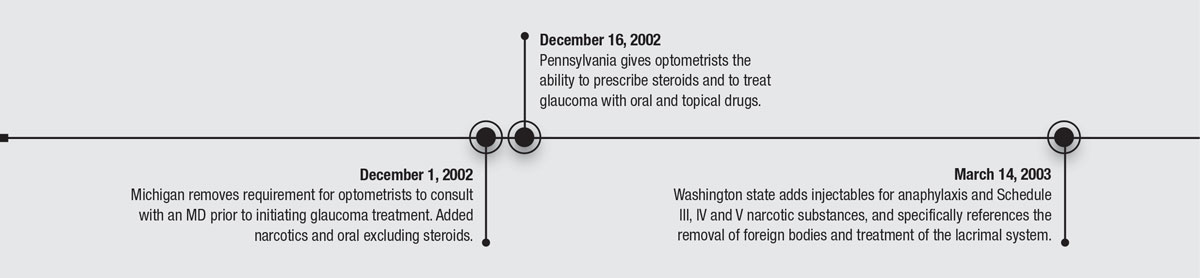

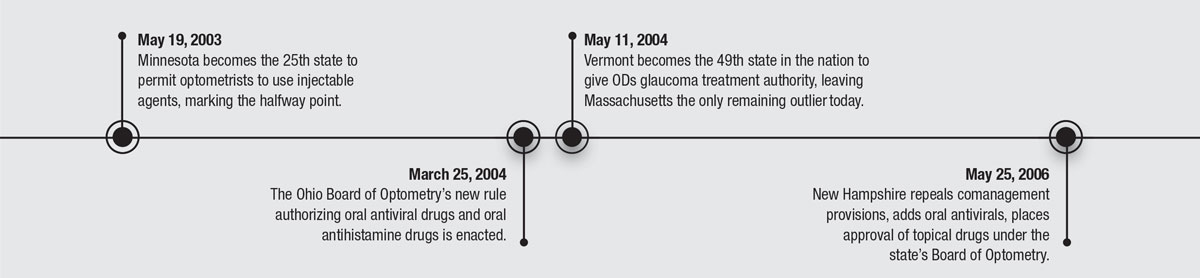

50 YEARS OF PROGRESS

Here's a review of some of the key historical dates that redefined optometry.

Eight Decades of ChicaneryOptometrists have had a target on their backs for decades. In 1937, Albert Fitch, who founded Pennsylvania College of Optometry, tried to pass a diagnostic and therapeutic drops bill. It was defeated in a razor thin 90-88 vote, through what Dr. Fitch would later write was nothing short of “chicanery.” According to Dr. Fitch’s biography, a member of Pennsylvania’s Health and Sanitation Committee, who happened to be a physician, posed as the committee’s chairman and “made a sobbing appeal to have the bill referred to his committee.” “The physician made a solemn promise that if the bill was referred to his committee, it would be reported back the next day with a recommendation for its passage. He said all this knowing full well that his committee, which contained more physicians than any other committee in the legislature, was not in favor of the bill and that his promise would never be kept.”1,2 1. Fitch A. My fifty years in optometry. 1959;2:337-55. 2. Bennett I. Improving the scope of practice for optometry. Optometry Cares—the AOA Foundation. Accessed October 1, 2018. |

What ODs are Up Against

Organized optometry is replete with complaints about interventions from ophthalmology lobbyists. Nowhere is this truer than in Massachusetts, the last state in the nation that doesn’t permit optometrists to prescribe any glaucoma medications. With the might of nearby Massachusetts Eye and Ear at its disposal, organized medicine has become a powerhouse lobby in the Bay State.

“Any time you’ve got a really strong research eye hospital” with robust state support, “they’ve built up a huge lobbying network over the years,” explains David Damari, OD, who serves as both dean of Michigan College of Optometry at Ferris State University and as president of ASCO.

And it’s not just Massachusetts. Other states with prominent eye hospitals—Pennsylvania (Wills Eye), Maryland and Washington DC (Wilmer) and Florida (Bascom Palmer) have all lagged in scope expansion. Pennsylvania didn’t get glaucoma drug authority until 2002. Florida didn’t have oral drug authority until 2013. The final three legend drug bills for optometry (barring the US Virgin Islands) were passed in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Washington, DC. On no issue do they fight harder than glaucoma care—which can bring in Medicare and Medicaid patients who will visit every three to six months.

“They fight to make sure that optometrists don’t gain confidence in glaucoma,” Dr. Damari adds, by insinuating that optometric inexperience might leave patients blind. “It’s not that we can’t treat, it’s that it’s the one thing ophthalmology holds on to because of reimbursements.”

The disparity, optometric advocates report, is apolitical. It’s not about red vs. blue; it’s about the green.

Medical Muckraking

One of the medical lobby’s weapons of choice has been publishing in mainstream news, trade publications and even peer-reviewed journals. You can practically track the status of any one optometric bill by uncovering a typical anti-optometry headline (usually something like “Leave Eye Surgery to the Surgeons”).

Dr. Pierce says the AOA doesn’t really engage in those battles. “We don’t get into tit-for-tat arguments in the press with ophthalmology. The truth of the matter is, since 1998 when Oklahoma first passed legislation to allow lasers, doctors of optometry have done so safely and effectively. We look at facts, and the fact is optometry is doing an excellent job of taking care of their patients,” he says, adding that there has been no rash of lawsuits, nor reports of patients losing their vision due to negligence or other documented problems in states where ODs have gained broader scope.

Within ophthalmology, fear-mongering has reached the peer-reviewed journals, too. Take for instance, a piece—which left Dr. Thomas apoplectic—from a February 2018 American Journal of Ophthalmology, arguing to establish an American Academy of Ophthalmic Associates.9 “The idea has merit for physician assistants, nurse practitioners, ophthalmic technicians, and ophthalmic photographers, but ophthalmologists should recognize the limited power it would have over optometrists, were it to be implemented,” wrote David Browning, MD, an ophthalmologist from Charlotte, NC. “It is easy to imagine a scenario in which an optometrist learns to administer intravitreal injections working as part of an ophthalmology-led team, and then leaves to practice without ophthalmic supervision in a state in which the right for optometrists to perform intravitreal injections has been legislated.”

To Dr. Thomas, this is both an example of how optometry is talked about when no ODs are in the room and a classic case of the medical establishment prioritizing itself over its patients. “Ophthalmologists are thinking more and more of recruiting PAs to do intraocular injections—who have had something like two to three weeks of training, whereas optometrists have had four years. But they’d rather have a PA they can control than an OD who is independent,” Dr. Thomas says.

In a JAMA Ophthalmology piece that’s been heavily circulated for the past couple of years, a researcher team with representatives from Michigan, Pennsylvania and Oklahoma delivered what some optometrists have since called a scare-tactic in the form of an article finding laser trabeculoplasties performed by optometrists had a 189% “increased risk” of requiring additional laser trabeculoplasty.10

Glaucoma specialist Murray Fingeret, OD, in a letter to the journal, called the study misleading and noted it isn’t even supported by the authors’ own data.11 “It is hard to understand the meaning of their conclusions without knowing whether treatments were performed in more than one session with 180˚ treatments or a single session with 360˚ treatments,” he wrote.11

A good deal of that retreatment rate might stem from the natural history of the disease rather than any optometric shortcomings. The study looked into the performance of 27 optometrists, all trained at Northwestern University, a program which recommends performing the 180˚ procedure first and only considering treatment of the other half if intraocular pressure doesn’t sufficiently come down.10,11 The JAMA study said nothing in terms of pressure reduction or complications. It appears the authors used a somewhat flexible definition of “risk.”

In other words, chicanery.

|

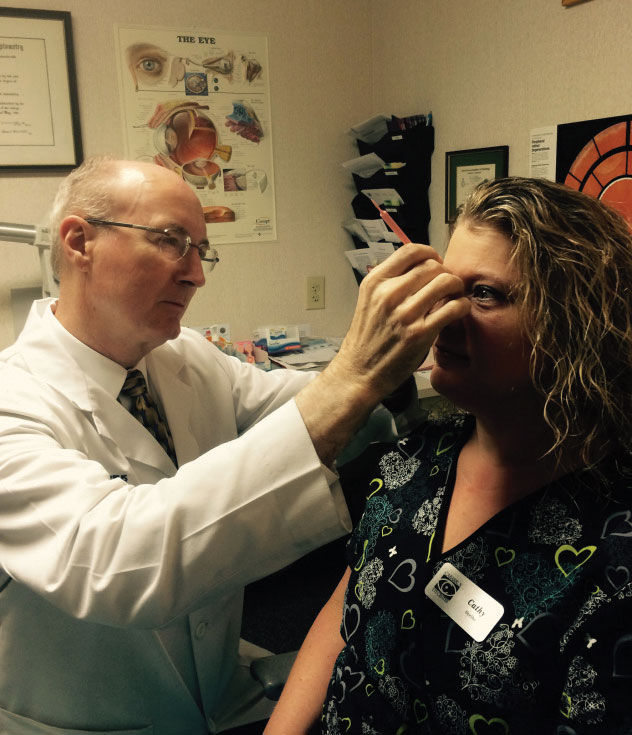

| Dr. Thomas, seen here demonstrating how he examines a patient, is a vocal advocate for allowing optometrists to use steroids in their treatments when necessary. Approximately 15 states still bar optometrists from doing so, but that may soon change as demographic realities make optometric scope expansion a priority. |

It’s the Economy, Doc

Baby boomers are at least 65 million strong, and living long.12 As people age into their 60s and beyond, pathology starts to increase. “That means more cataract patients, more posterior capsular opacification patients and more glaucoma patients,” explains Nate Lighthizer, OD, an educator out of Northeastern State University Oklahoma College of Optometry, who takes a special interest in laser procedures. With this demographic shift, “ophthalmologists are going to have their hands full keeping up with cataracts and the wet form of macular degeneration” among other things, says Dr. Thomas.

There’s been another shift, too. Optometry’s numbers are increasing while ophthalmology’s remain flat—and may even be decreasing, if you consider that nearly half of American ophthalmologists are older than 55 and optometry is graduating more students than ever.13 While optometry is trying to find ways to expand its residency programs, ophthalmology’s have stayed relatively flat for nearly a decade and its total number of applicants has decreased over that timespan by more than 100.14

For patients, these trends mean ophthalmologists are fewer and farther between. This fact has worked in optometry’s favor, helping it achieve its broadest scopes of practice in the rural states Kentucky, Oklahoma and Louisiana. Dr. Mangan—who, until recently, practiced in Kentucky—mentions that while he lived there, he’d have patients who’d walk to his practice, sometimes even with urgent presentations. “I’ve had patients who didn’t drive. For them, it’s important that there’s access,” he says. Without the expansions in optometry’s scope over the years, he might have to send them to another office, which could compromise the patient if their need was timely. Besides, Dr. Mangan says, optometrists “have more training and expertise in eye disease than any family physician or emergency room doctor could. We typically have better diagnostic equipment, too.”

It doesn’t take a sociologist to see optometry is primed to fill a need, and a handful of the roles ophthalmology has traditionally filled are primed to migrate to optometry. “We are often the first encounter a patient will have with the health care provider. Last year, we diagnosed hundreds of thousands of previously undiagnosed diabetes, we are definitely an entry point into the health care system—that doesn’t need to be hampered by outdated optometry acts,” notes Dr. Pierce.

|

| Dr. Lighthizer performs a YAG capsulotomy. This non-invasive laser procedure represents the highest rung of optometry’s current scope of practice. |

For the most part, these roles include the kind of work optometry doesn’t need any new indications for, but of those items that do necessitate legislative change—chief among them involving laser, minor surgical procedures and amniotic membranes—organized optometry is taking the fight to the statehouses, just as it did in the 1970s and 1980s for diagnostic drugs and 1980s and 1990s for therapeutic drugs.

They’re appealing to lawmakers by explaining how, as Dr. Lighthizer puts it, “a two- to five-minute in-office procedure can restore a 20/40 or 20/50 patient’s vision back to 20/20 within hours to days.”

“I envision, in the next 10 to 20 years, more and more states will embrace scope expansion,” he adds.

Part of that will be chalked up to appeals to legislators, but the impact technology has on redefining what an OD can do shouldn’t be ignored either.

We Have the Technology

“If you’re a refraction-centric optometrist, you’re going to be replaced by technology,” predicts Dr. Thomas. “But if you’re a medically oriented optometrist, there’s nothing out there to replace solid cerebral clinical judgment.” This is a common sentiment among optometrists and it’s driven many changes in both legislation and education, both of which are facilitated by technological advances that are making it possible for ophthalmologists and optometrists alike to function more precisely, with more robust data and, ultimately, practice at higher levels.

In fact, technology is inextricably wrapped around optometric scope of practice laws. This is the part that’s unique to optometry. When a new surgical technique enters into cardiology or oncology, the surgeon may have to be certified by an independent, non-governmental body, but its application is not legislated. The government doesn’t say that a dermatologist but not a family physician can use liquid nitrogen to freeze off a wart. However, most optometric regulations are guided by laws of “inclusion” rather than “exclusion.”15 Inclusive laws define the limits of what optometrists can do; exclusive laws list what optometrists cannot do. In other words, the law in most states must explicitly include particular procedures in optometry’s scope.15

This is where Oklahoma, the first state to gain laser authority (in 1998) and the tenth to gain authority to use injectable agents (in 1994), is so well positioned. The state has an exclusionary law. “The nice thing about that,” explains Dr. Lighthizer,” is that when a new procedure comes out, it isn’t on the exclusionary list, so ODs don’t have to go back to the legislature and ask for permission.” For instance, when SLT was approved for use in glaucoma patients in 2001, optometrists in Oklahoma could start using it the moment they were certified and set up for it. Today, SLT is beginning to be recognized as a first-line therapeutic option.16 That means, if more states permit optometrists to use lasers, patients could have the option of seeing the eye doctor they’ve been visiting their whole lives for a non-invasive, in-office procedure before they ever see an ophthalmologist. This is precisely the kind of structure California’s bill is aiming for.2

One Giant LeapIt took nearly 30 years after the failure of Albert Fitch’s historic 1937 attempt at optometric expansion before the modern era of optometry finally began. On January 16, 1968, A. Norman Haffner, OD, finally put his foot down and settled a debate that had been essentially splitting the profession down the middle for decades. His words at a meeting of optometric leaders that day—“The optometrist is a primary care provider and the optometrist has a role in the diagnosis and treatment of ocular pathology”—seem a simple statement of fact today, but at the time, it was radical. The previous self-definition of a “drugless profession” was out.1 Within three years, Rhode Island would pass the first diagnostic drug bill and optometry was off to the races. Therapeutic drops followed a similar path, with the first bill past in West Virginia in 1976. Before this run, a mere conjunctivitis patient had to choose between trying to book an eye surgeon for treatment or relying on a family practitioner who wouldn’t have particular training in eye care. The primary care role specifically for eyes—the biological structure that most informs humans’ perception of the world and most influences quality of life—simply didn’t exist. As optometry enters its next phase, its advocates will have to look to this history to guide how to best serve patients in need. 1. Eger M. The Airlie House Conference. Journal of the American Optometric Association. 1969:40(4):429-31. |

Education

The argument against optometry’s scope expansion often portrays ODs as lacking the educational background to capably perform certain tasks. But technology is leveling the playing field to the point where the argument is frequently more about equipment access than actual medicine. “Every optometrist trained on a slit lamp can do a YAG,” explains Dr. Lighthizer. “It’s the same technique. If you can do gonioscopy, you can do an SLT—it is a very similar skill set.”

And if it’s the OD’s residency training that’s being questioned, Dr. Damari, points out that ophthalmology is facing a similar problem. “There just aren’t enough patients who need these procedures in the United States,” he says. “Removing chalazia, minor suturing, laser procedures for angle closure—there’s barely enough for residency training in ophthalmology to do them, let alone for the 1,500 to 1,700 optometry students who graduate every year to get enough experience that would make us comfortable to say they’ve had enough experience.”

That doesn’t mean that optometry students aren’t learning the ropes; it only means that, like ophthalmology, most of the experience is developed outside of residency programs. Every optometry student, regardless of institution, is trained as though they’re going to practice in a state that permits them to perform laser and lid lesion procedures. In fact, nearly every school signs and

submits to the optometric boards in Kentucky and Louisiana an affidavit to that effect.

Don’t Fight, Adapt

Optometry has always been a self-defined profession and legislation has always been the mechanism, however imperfect, to broaden that definition. But what if optometry no longer needs legislative action to enable growth? Consider the changing demographics, advanced technologies and the general shift toward medical optometry.

“I don’t believe that our future will be much bolstered by any procedure,” as many become supplanted by newer ones in time, offers Dr. Damari.

Why bother fighting for procedures that may not even exist in a few years instead of refocusing optometry’s efforts towards the more “high-touch” aspects of health care?17

“If we limit our imagination to only training on procedures, it’s not going to benefit our profession the most” says Dr. Damani, who points to telemedicine, home diagnostics and quality of life improvement as some of the biggest changes to practice on the horizon. These will include patient management techniques that optometrists are already skilled at, with the possible addition of helping patients understand the kinds of wellness data gathered by wearable diagnostic tools and visual therapy techniques that can protect the eyes of an increasingly near-working population.

As ophthalmology eschews medical management in favor of surgery, optometry will catch all those patients. As refraction either becomes automated or the primary domain of big box retailers and their optical departments, maybe the time for optometry to split is here again—just as it was in 1968.

1. American Optometric Association. AOA alerts states to NAVCP-backed noncovered services bill. www.aoa.org/news/advocacy/aoa-alerts-states-to-navcp-backed-noncovered-services-bill. March 10, 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018. 2. California legislative information. AB-443 Optometry: scope of practice. leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB443. October 9, 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018. 3. Alaska Optometric Association. Governor Bill Walker signs HB 103 into law. akoa.org/news_manager.php?page=14408. Accessed October 1, 2018. 4. Miller N. Florida optometry bill clears House subcommittee. Orlando Sentinel. March 15, 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018. 5. Florida Senate. CS/HB 1037: Optometry. www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2017/1037/ByVersion. Accessed October 1, 2018. 6. Morrill J. ‘Classic dirty politics’: This deep-pocketed group is trying to sway an NC election. The Charlotte Observer. www.charlotteobserver.com/news/politics-government/election/article209898514.html. May 1, 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018. 7. Horsch L. These 5 NC Republicans won’t get another term in the legislature. News Observer. www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/article210721329.html. May 9, 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018. 8. North Carolina General Assembly. Biography, Senator David L. Curtis. www.ncleg.net/gascripts/members/viewMember.pl?sChamber=S&nUserID=378. June 30, 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018. 9. Browning D. Correspondence: Physician assistants and nurse practitioners in ophthalmology-has the time come? JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;191(7):166-7. 10. Stein J, Zhao P, Andrews C. Comparison of outcomes of laser trabeculoplasty performed by optometrists vs ophthalmologists in Oklahoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(10):1095–1101. 11. Pollard K, Scommegna P. Just how many baby boomers are there? Population Reference Bureau. www.prb.org/justhowmanybabyboomersarethere. April 16, 2014. Accessed October 1, 2018. 12. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014 Physician Specialty Data Book. members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/14-086%20Specialty%20Databook%202014_711.pdf. November 2014. Accessed October 1, 2018. 13. Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology residency match summary report 2018. sfmatch.org/PDFFilesDisplay/Ophthalmology_Residency_Stats_2018.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018. 14. Raji J. Louisiana optometry: an exclusive law. Optometry Students. www.optometrystudents.com/louisiana-optometry-an-exclusive-law. July 11, 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018. 15. de Leon J, Latina M. Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty. Quantel Medical. www.quantel-medical.com/upload/products/product-9/download_file_en_Selective_laser_trabeculoplasty_-_JM_DE_LEON__M_LATINA_-_09.2015.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018. 16. Realini T. First-line selective laser trabeculoplasty: Has its time arrived? Eyeworld. www.eyeworld.org/article-first-line-selective-laser-trabeculoplasty--has-its-time-arrived. August 2013. Accessed October 1, 2018. 17. Menton M. Getting high-tech to remain high-touch. Health Tech Magazines. www.healthtechmagazines.com/getting-high-tech-to-remain-high-touch. Accessed October 1, 2018. 18. American Optometric Association. Optometric prescriptive authority/scope of practice chronology. August 15, 2014. 19. American Optometric Association. Scope of practice enactments – timeline. July 2018. 20. American Optometric Association. Scope of practice amplification laws. January 6, 2018. 21. Nguyen Q. Optometry scope of practice in each state. New Grad Optometry. newgradoptometry.com/optometry-scope-of-practice-united-states. April 20, 2018. Accessed August 1, 2018. 22. Alaska Optometric Association. Governor Bill Walker signs HB 103 into law. http://akoa.org/news_manager.php?page=14408. July 26, 2018. Accessed September 4, 2018. 23. Chan J. What is the scope of practice in my state? Optometry Students. www.optometrystudents.com/legislative-list. November 20, 2016. Accessed September 4, 2018. |