An internist referred a 73-year-old white male to our clinic. An earlier examination by the internist revealed a drawn mouth and watery eye on the right side of the patients face. The patient had no weakness in his arms or legs, and his blood pressure was normal.

A neurologist examined the patient a week earlier for a possible stroke on the right side. The neurologist initially diagnosed right Bells palsy and prescribed Zovirax (acyclovir, GlaxoSmithKline) 400mg t.i.d. and oral prednisone 20mg b.i.d. The neurologist also ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which revealed an old lacunar infarct in the right corona radiata, but the etiology of the neurological deficits was not apparent. Carotid doppler revealed moderate plaque formation in the internal carotid artery and mild stenosis in the 1% to 39% range bilaterally. At this point, the differential diagnosis was Bells palsy or stroke.

The patients ocular history was unremarkable, but his medical history was significant for hypercholesterolemia, cardiac disease, bronchitis and emphysema. He was taking Lescol XL (fluvastatin, Novartis), Advair (fluticasone and salmetrol, GlaxoSmithKline) and a multivitamin. He also was using Systane (polyethylene glycol and polypropylene glycol, Alcon) b.i.d. and Lacrilube cream (bland ophthalmic ointment) twice daily. The patient said the internist told him to patch the right eye before going to bed. The patient was allergic to penicillin and codeine.

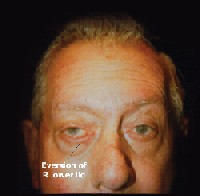

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/80 O.D. and 20/40 O.S. There was eversion of the right lower lid, epiphora, droopy mouth corner, absence of distinct facial creases and skin folds on the right side (figure 1).

|

| 1. The patient presented with eversion of the right lower lid and a droopy face on the right side. |

The second to 12th cranial nerves appeared normal, except for possible decreased sensation of the right fifth cranial nerve and a facial nerve palsy on the right side. Our patients mouth area, facial expression muscles and eyelids on the right side were weakened, but furrowing across the forehead on brow lift was demonstrated (figure 2).

|

| 2. The patient demonstrated furrowing of the forehead on both sides on brow lift. |

Diagnosis

We ruled out Bells palsy and diagnosed the patients condition as left upper neuron facial palsy. We suspect the neurologist prescribed oral prednisone and acyclovir as prophylaxis for herpes infection.

Treatment and Follow-up

We prescribed Ciloxan ointment (ciprofloxacin, Alcon) in the morning and before bedtime, Systane drops every few hours while awake and Genteal gel (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, Novartis Ophthalmics) before bedtime. We taped his right lower and upper lids together on the lateral canthus to narrow the palpebral fissure, thus avoiding corneal exposure from lagophthalmos. Oral prednisone and acycylovir were discontinued.

One week later, distance acuity improved to 20/50 O.D., and the corneal ulcer was resolving. But, the patient still had the lagophthalmos and right facial weakness with positive brow lift.

Seven weeks later, the patient reported that vision in his right eye was improving, and that there was less tearing. There was significant improvement of facial paresis on the right side with better lid position and lid closure on blinking. There was an inferior thinning of the right cornea.

The patient continued to use Systane b.i.d. and Genteal gel before bed time. On the last documented visit, he was using only Systane b.i.d. The keratitis resolved completely, but there was corneal thinning inferiorly.

Discussion

The facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) originates in the pons, passes through the stylomastoid foramen and enters the parotid gland, where it divides into its main branches. The facial nerve consists of motor and sensory parts, and both parts emerge at lower border of pons. After passing through the stylomastoid foramen and inside the parotid gland, the motor part divides into branches to innervate muscles of the face (temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical) and neck (posterior auricular, digastric and stylohyoid). These branches further divide into several smaller nerve fibers to innervate the muscles of the face and neck, namely the forehead, eyelids, facial expression, mouth, salivary glands and outer ear.

The forehead receives bilateral cortical innervation from decussation of coticobulbar fibers at the seventh nerve nucleus. So, a one-sided supranuclear lesion from a stroke or tumor will spare the upper face and allow brow lift (frontalis muscle) and closure of upper eyelids (orbicularis oculi and corrugator supercilii muscles).1

This case report looks at the difference between two types of palsy:

Upper motor neuron palsy. This type of palsy causes weakness of the lower face only. Forehead wrinkles remain intact, and there is closure of both upper eyelids. Upper motor neuron palsy implies the presence of a lesion contralateral to the side of facial weakness. This lesion disrupts the facial motor fibers somewhere in its course from the primary motor cortex to the facial nucleus within the pons.

Lower motor neuron palsy. Complete, unilateral facial paralysis indicates peripheral lower motor neuron palsy. It likely occurs due to compression or inflammation of the facial nerve just before the nerve exits the skull.2 Signs of peripheral lower motor neuron palsy include loss of forehead and brow wrinkles, inability to close both eyelids, flattening of nasolabial folds, drooping of the lower lid and an asymmetrical smile. Lower motor neuron palsy implies the presence of a lesion that involves the facial nerve nucleus in the pons or along the course of the facial nerve ipsilateral to the side of facial weakness.

Bells palsy is a lower motor neuron palsy that causes a complete unilateral facial paralysis. If the upper face is spared from a supranuclear lesion that results from a stroke or tumor, consider Bells palsy in the diagnosis. Incidence of Bells palsy ranges from 15 to 40 cases per 100,000 people per year.3

Bells palsy traditionally has been considered to be idiopathic in nature with acute onset. Growing evidence, however, links reactivation of herpes viruses (primarily varicella zoster virus and herpes simplex virus type 1, or HSV-1) with development of many of these idiopathic palsies.1,2 HSV-1 reactivation may be a cause of acute facial paralysis in children and adults.4

Consider: In one study, genome analysis revealed fragments of HSV-1 DNA in the endoneurial fluid and posterior auricular muscle biopsy specimens in a majority of patients with idiopathic facial paralysis.5 No such DNA markers were noted in the samples taken from control patients or those who had facial paralysis from other causes.

In another study, researchers collected tear fluid and saliva from 16 patients who had Bells palsy.6 They found HSV-1 DNA in 12% of the 244 specimens collected, leading them to conclude that reactivation of HSV-1 on the affected side is a pathogenic factor for Bells palsy. Further, the researchers said a reactivation of HSV-1, even on the unaffected side, may be generated in the early phase of this disease.

After reactivation, the virus can destroy the ganglion and Schwann cells, leading to demyelination of the facial nerve. The facial nerve then becomes compressed and ischemic in its narrow passage through the temporal bone, causing conduction block and nerve degeneration.

Others, however, have challenged the connection between HSV and Bells palsy. Researchers in Switzerland were unable to detect HSV-1, HSV-2 or varicella zoster virus DNA in ganglion scarpae or muscle biopsy results of both control subjects and Bells palsy patients.7 They detected human herpes virus-6A/B in tears of 30% of the Bells palsy subjects, but said this did not explain the direct association with Bells palsy. Rather, they believe that identification of an active replicating virus is necessary.

Still, numerous triggers known to reactivate HSV-1including fever, upper respiratory tract infection, dental extraction, menstruation, stress and exposure to coldalso have been found to cause Bells palsy.5 A small percentage of Bells palsy cases are caused by virus, infection, influenza, Lyme disease, otitis media, sarcoidosis, syphilis and Mycoplasma pnumoniae.3,5,8-10

Other causes of facial paralysis are diabetes, neoplasms (tumors of the parotid gland, tumors of the base of the skull and acoustic neuroma) and facial trauma.11,12 One study found a strong association between an inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine (used in Switzerland) and Bells palsy.3 Neuroimaging (MRI or computed tomography) and serology tests are warranted to determine the underlying cause for facial paralysis.

Nerve dysfunction in Bells palsy can cause retroauricular pain, facial numbness, epiphora, parageusia, decreased tearing and hyperacusis (augmented hearing). Patients with facial nerve palsy are also at risk for exposure to keratitis, corneal scarring and possible vision loss.

Treatment of Bells palsy often involves combination antiviral (acyclovir) and anti-inflammatory (prednisone) therapy.2,12,13 The antiviral is used because of probable involvement of herpes virus. Steroids reduce inflammation and edema that block the conduction of the facial nerve as it passes through the stylomastoid foramen. Combination therapy initiated within 72 hours of presentation provides a superior prognosis for faster recovery of voluntary muscle movement and reduces the risk of permanent damage.14,15

However, these treatment options are somewhat controversial. Some researchers say there is little evidence that corticosteroids and antivirals are effective and that more randomized controlled trials with greater numbers of patients are needed to determine whether these therapies offer real benefit (or harm).16,17 Also, therapy does not always cure Bells palsy, even if initiated at the first signs of the disease, because nerve damage may have already occurred.

On recovery, patients may still have residual eyelid weakness, involuntary spasms or contractures of the eyelids or facial muscles, facial myokymia and aberrant regeneration leading to jaw-wink phenomenon or lacrimation with chewing (crocodile tears).1,2 In one study of 69 patients with peripheral facial nerve palsy (68% of whom were classified as having Bells palsy), the final outcome was good with complete recovery in 77%, slight sequelae in 20% and moderate sequelae in 3%.9 No patients experienced severe sequelae.

The O.D. may be the first doctor to see patients with facial nerve palsies. We must be able to distinguish different facial nerve palsies, provide appropriate referral to other doctors and provide appropriate care for dry eyes and keratitis secondary to lagophthalmos.

Dr. Poudyal graduated from Indiana University School of Optometry in 2004 and currently practices at Eyeglass World in Toledo, Ohio. Dr. Peplinski practices at Bennett & Bloom in Louisville, Ky. Dr. Poudyal thanks Bennett & Bloom for letting him use this case for publication.

1. Skorin L Jr. How to tell Bells from the masqueraders. Rev Optom 2003 May 15;140(5):67-73.

2. Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bells palsy. BMJ 2004 Sept 4;329(7465):553-7.

3. Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bells palsy in Switzerland. N Engl J Med 2004 Feb 26;350(9):896-903.

4. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Aizawa H, et al. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation is an important cause of acute peripheral facial paralysis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005 Feb;24(2):97-101.

5. Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, et al. Bells palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med 1996 Jan 1;124(1 Pt 1):27-30.

6. Abiko Y, Ikeda M, Hondo R. Secretion and dynamics of herpes simplex virus in tears and saliva of patients with Bells palsy. Otol Neurotol 2002 Sep;23(5):779-83.

7. Linder T, Bossart W, Bodmer D. Bells palsy and herpes simplex virus: fact or mystery? Otol Neurotol 2005 Jan;26(1): 109-13.4.

8. Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2003 Nov 15;362(9396):1639-47.

9. Ljostad U, Okstad S, Topstad T, et al. Acute peripheral facial palsy in adults. J Neurol 2005 Mar 23;[Epub ahead of print].

10. Volter C, Helms J, Weissbrich B, Rieckmann P, Abele-Horn M. Frequent detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Bells palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2004 Aug;261(7):400-4.

11. Keane JR. Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology 1994 Jul44(7): 1198202.

12. Roob G, Fazekas F, Hartung HP. Peripheral facial palsy: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Eur Neurol 1999 Jan; 41(1):3-9.

13. Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: Steroids, acyclovir and surgery for Bells palsy (an evidence based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001 Apr 10; 56(7):830-6.

14. Hato N, Matsumoto S, Kisaki H, et al. Efficacy of early treatment of Bells palsy with oral acyclovir and prednisolone. Otol Neurotol 2003 Nov;24(6):948-51.

15. Lagalla G, Logullo F, Di Bella P, et al. Influence of early high-dose steroid treatment on Bells palsy evolution. Neurol Sci 2002 Sep;23(3):107-12.

16. Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Ferreira J. Corticosteroids for Bells palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004 Oct 18;(4):CD001942.

17. Allen D, Dunn L. Aciclovir or valaciclovir for Bells palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD001869.