Annual Dry Eye ReportCheck out the other feature articles in this month's report: |

The past 10,000 years have given rise to many changes in our nutritional environment, with enormous implications. A less varied diet and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle has led to an increased risk of chronic conditions such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, obesity, diabetes and many cancers.1 Today’s Western diet includes too many dietary grains and fatty foods and not enough fruits, vegetables and proteins. As a result, the number of omega-6 fatty acids in our diet are significantly higher while the amount of omega-3 fatty acids continues to decrease.

The connections between omega-3, omega-6 and inflammation are well documented in the medical literature, leaving some to speculate that this nutritional shift plays a role in the pathogenesis of dry eye disease (DED).

DED in Modern Society

Dry eye’s impact on society is significant. Based on the literature, the incidence of DED ranges between 5% and 30% in individuals older than 50, which, at the upper range, makes it more prevalent in the US population than diabetes, cancer and heart disease combined.2-4

The irritation, blurred vision and eye fatigue associated with dry eye lead to a decrease in quality of life by impairing a patient’s ability to read, drive and work on the computer.5-7 Studies show that when direct costs such as office visits, tear therapies and supplements are combined with indirect costs (e.g., loss of productivity), the yearly impact of DED on the US economy nears $55 million.5

Practitioners have a variety of treatments in their armamentarium to combat this disease, including ophthalmic lubrication, lid and meibomian gland therapy, anti-inflammatory eye drops and punctal plugs.9 While these treatments can help to manage dry eye, clinicians continue to search for new treatment options with a particular focus on those that address the underlying disease process.10

The search for dry eye answers has led researchers to question whether nutrition, specifically the balance of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and their role in inflammation, might hold the key.

|

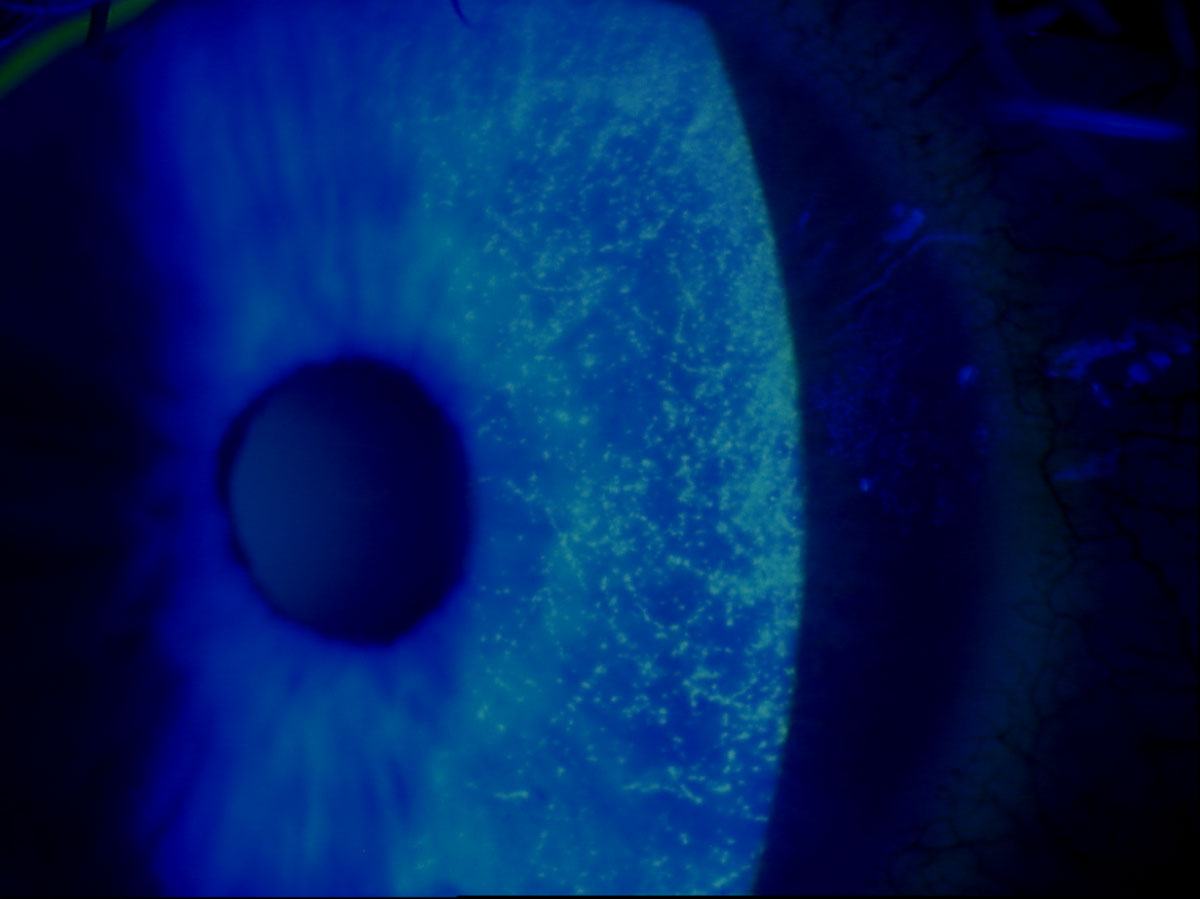

| This slit lamp photo demonstrates sodium fluorescein staining of a patient’s eye with punctate keratitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Fatty Acid Basics

Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) consist of two primary categories: omega-6 and omega-3. Omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs are derivatives of the essential fatty acids (EFAs) alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and linoleic acid (LA).11,12 ALA is an omega-3 fatty acid found in flaxseed and chia that is converted by the body to the longer chain PUFA eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) then docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Because this process is inefficient in humans, we must obtain EPA and DHA from food sources or supplements.12-15 DHA and EPA are found naturally in fish and krill oils, as the fish consume microalgae that produce them.12

LA is an omega-6 fatty acid found in vegetables oils, nuts, eggs and meat.20 Once ingested, it is desaturated and elongated to form the longer chain PUFA gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) then arachidonic acid (AA).15,17 GLA, which is found in black current seed oil and evening primrose oil, exhibits anti-inflammatory properties while AA is pro-inflammatory. GLA increases the amount of dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA), which can then be converted to either AA or to 1-series prostaglandins. Omega-3, specifically EPA, competes with the conversion of DGLA to inflammatory AA, thus increasing the production of anti-inflammatory 1-series prostaglandins.

Biochemically, to get the full benefits of increased GLA, you should ensure the patient also has adequate levels of EPA either through their diet or supplementation.19,20 GLA can provide relief from chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and improve symptoms in patients with dry eye and Sjögren’s.17-19,21

Both omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids form eicosanoids, which are signaling molecules within the body. Eicosanoids from omega-3 are key to the function of the cardiovascular, pulmonary, immune and endocrine systems while omega-6 eicosanoids are mediators of vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation which contribute to inflammation.12

Simply stated, omega-3 fatty acids are considered anti-inflammatory while omega-6 fatty acids are primarily pro-inflammatory.22,23 Though some degree of inflammation is essential to the body’s ability to prevent infection and recover from injury, excessive amounts can contribute to chronic disease processes. Research shows that the decline in omega-3 in our tissues allows for its replacement with increased amounts of omega-6.16 Thus, a diet appropriately balanced in omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids provides significant health benefits.

There is a beneficial anti-inflammatory shift within the body when the concentration of EPA and DHA is greater than that of AA due to competition in the synthesis of eicosanoids.12,14 An omega-6 to omega-3 ratio range from 1:1 to 4:1 is consider optimal for the majority of disease process.1

|

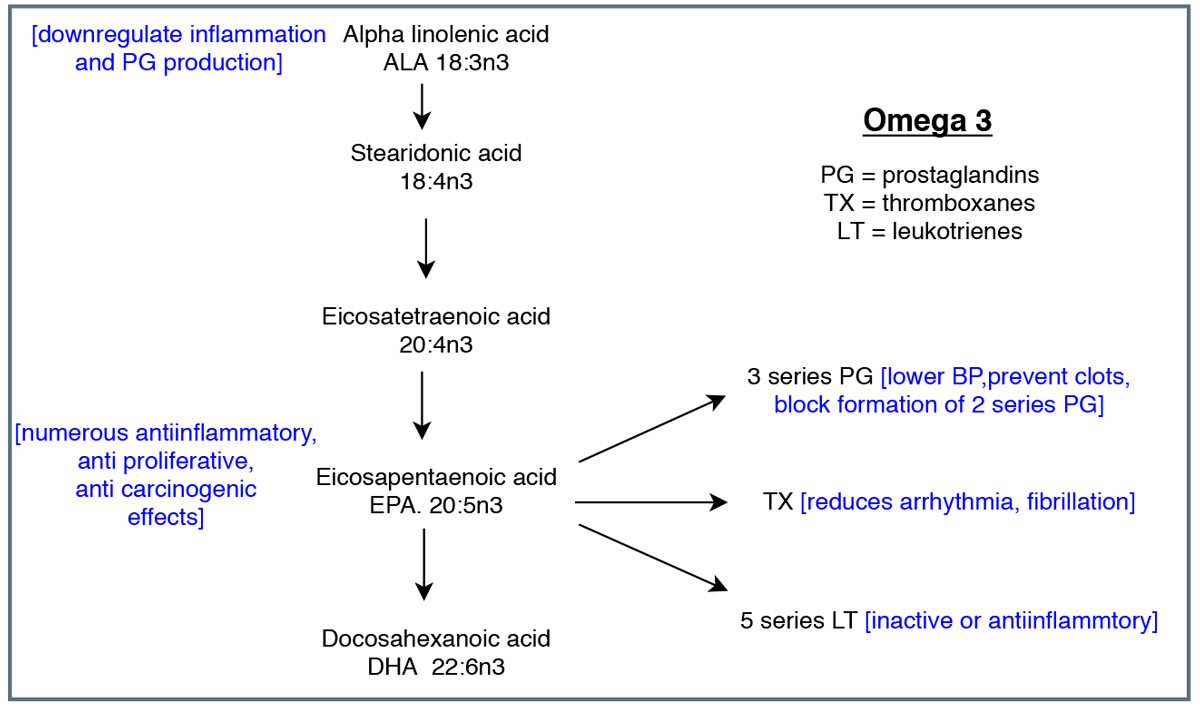

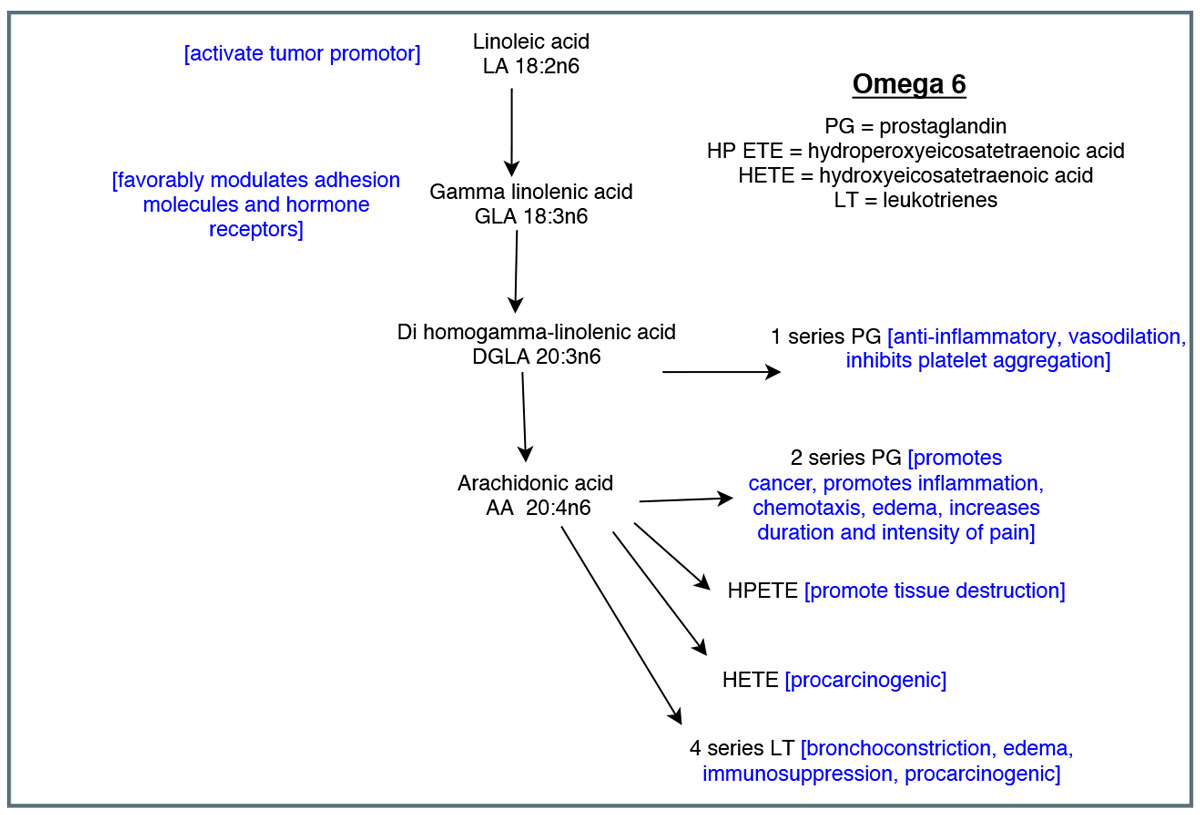

| These diagrams show the cascade of omega-3 (above) and omega-6 (below) metabolism and eicosanoids. Adapted from Vasquez A.39 Click images to enlarge. |

|

Dietary Shifts

Prior to the agricultural revolution, humans were primarily hunters and gatherers. Lean meat, fish, leafy green vegetables, fruits, berries and honey were readily available, and the human diet had a vast degree of variety.1 Wild game and plants contributed an appreciable amount of omega-3 to the human diet, creating a 1:1 ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids.1,16,24

The advent of the agricultural revolution brought about primarily three dietary changes for which there is no evolutionary precedent in our species.1

First, cereal grains entered the human food supply, and quickly become increasingly central to our diet; grains now provide the greatest number of calories in the American diet.1,16 Cereal grains are high in carbohydrates and omega-6 and are low in omega-3 and antioxidants.1

Second, poultry and soybean oil consumption increased exponentially, and soybean oil’s contribution to food calories increased 1,000-fold while poultry’s contribution increased four-fold. This resulted in a three-fold increase in essential omega-6 but only a two-fold increase in essential omega-3.16

Lastly, farmers in the 1950s began to use high-energy grain feed for cattle, which decreased days on feed and improved marbling—or intramuscular fat—in the final product.11 While there is no significant difference in omega-6 content between the two feeding regimens, grass-fed beef has higher concentrations of omega-3 and has a more favorable omega-6 to omega-3 ratio. Gradually over time, consumers have become accustomed to the flavor profile of grain-feed beef and often prefer it to grass-fed beef.11

Together, the increased consumption of cereal grains, advent of the vegetable oil industry and changes in livestock feed have led to a dramatic increase in the amount of omega-6 in our diet.1 The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 in Western diets has now skyrocketed to approximately 15:1.25

The Roots of DED

The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II defined dry eye as a disease “in which tear film instability and hyper-osmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neuro-sensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”5 While numerous risk factors contribute to dry eye, inflammation of the lacrimal gland, ocular surface and meibomian glands is a key contributor.5,19,25

When ocular surface inflammation occurs, inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandin E2 and inflammatory leukotrienes are synthesized from eicosanoids and lead to epithelial cell apoptosis, goblet cell loss and corneal barrier disruption resulting in DED.14,19,25,26 Omega-3 fatty acids competitively decrease the production of inflammatory mediators and inhibit killer cell activity.19 Cellular research shows that the efficacy of omega-3 in the context of dry eye may be related to its influence on the composition of lipids produced by meibomian gland epithelial cells in addition to its anti-inflammatory properties.14,27

|

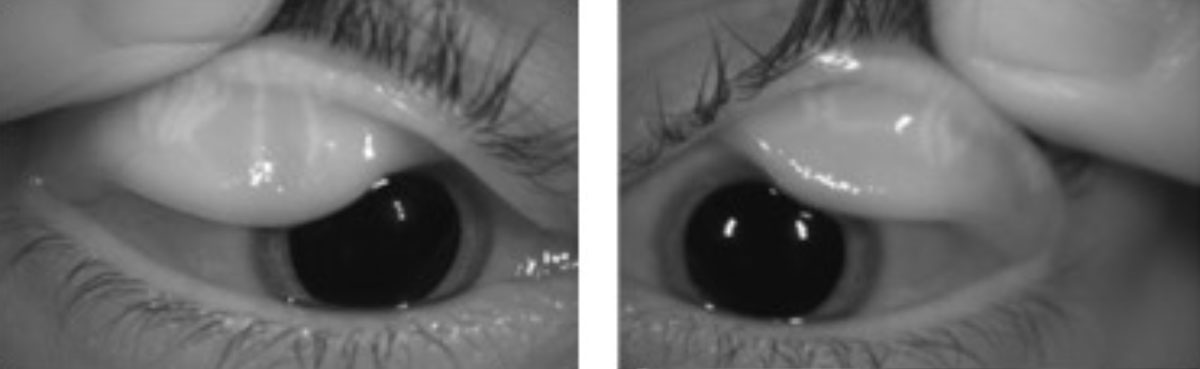

| This patient’s meibography reveals signs of severe dry eye in a patient with meibomian gland dysfunction. Click image to enlarge. |

Where Fatty Acids Fit In

Studies in the 1970s found that deaths due to coronary heart disease were particularly low in Inuit populations that have a diet high in seafood.11 Researchers discovered that the omega-3 PUFAs in the seafood were responsible for the positive health effects.11 They also found that a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids has wide-ranging health benefits such as lower serum triglyceride concentrations, improved cardiac function and lower C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor.13,23,28

The importance of a balaned omega-6 to omega-3 ratio was first addressed in the 1990s when researchers realized that large amounts of omega-6 in our diet causes the formation of more AA than EPA.29 The increased AA eicosanoids lead to allergic and inflammatory disorders and continued proliferation of cancer cells.25

Although many studies have found a correlation between omega-3 fatty acids and DED, the Women’s Health Study in 2005 was the first systematic study to establish the potential protective role of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in the treatment of DED.24 Of the approximate 32,000 women included in the study, 4.7% gave self-reports of dry eye. Food frequency questionnaires showed a 68% decrease in self-reported history of dry eye in women who consumed greater than five servings of tuna per week. While the researchers found no correlation between high omega-6 intake and dry eye, they noted that subjects with a high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio (15:1 or greater) were twice as likely to have DED compared with subjects with a lower ratio.18,24

Since that study, numerous others have evaluated these fatty acids and DED. One of the first omega-3 dry eye clinical trials in 2011 found that the use of omega-3 supplements resulted in improvements in symptoms and tear production.30 Other investigations show that patients on omega-3 (EPA/DHA) supplements experience significantly greater improvements in symptoms and signs of dry eye than patients receiving placebo.10,31-34 Even combinations of omega-3 and the omega-6 GLA can provide subjective improvement in dry eye symptoms as well as a decrease in corneal inflammatory markers.19,21 Research shows omega-6 supplements with combined LA and GLA resulted in decreased corneal inflammatory markers, an increase in tear meniscus height and improved symptomatology.18,19

Despite the growing body of literature, none of it shows conclusive findings regarding omega fatty acids and dry eye. Comparisons between trials are complicated by the fact that eligibility criteria, supplement content/dosage, placebo content and outcome measures all vary considerably.9

Even the American Academy of Ophthalmology remains cautious in its support of omega fatty acid therapy in the treatment of dry eye due to lack of consensus. It’s preferred practice patterns state that “education regarding potential dietary modifications (including oral essential fatty acid supplementation) should be included” within the initial treatment of dry eye and that “the use of essential fatty acid supplements for dry eye treatment has been reported to be potentially beneficial.” However, it also notes the recent findings from the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) study and its failure to support the benefit of oral fatty acids over placebo.2

DREAM Raises Questions

In 2018, the DREAM study research group published findings from a randomized controlled trial conducted at 27 ophthalmologic and optometric clinical centers in the US. In the study, dry eye patients were assigned to either an active supplement containing 3,000mg fish-derived omega-3 EPA/DHA or a placebo of 1,000mg refined olive oil.9,35 Patients were maintained on their assigned supplement for 12 months and their ocular health and symptoms were monitored. The primary outcome was the mean change from baseline in the ocular surface disease index (OSDI) score with secondary outcomes of corneal signs. It is frequently touted as one of the most ‘real-world’ omega supplement studies to date in that patients with inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s were included and patients could continue certain dry eye treatments.9

At the end of 12 months, both DREAM study groups experienced a clinically significant decrease in their OSDI scores compared with baseline, and there was no significant difference between the two groups in signs of DED. The fact that the change in OSDI scores did not differ significantly between the active and placebo supplement groups confounded many in the dry eye world.9

Researchers have proposed multiple explanations as to why the DREAM study did not show the benefit of omega-3 over placebo in the treatment of dry eye, including the potential anti-inflammatory effects from the refined olive oil placebo.35 The lack of GLA in the active supplement could also play a part in the similar efficacy results between the experimental and placebo groups.17 Finally, the real-world nature of the study is potentially a complicating factor because many patients were already using treatments such as artificial tears and lower dosage omega fatty acid supplements.35

|

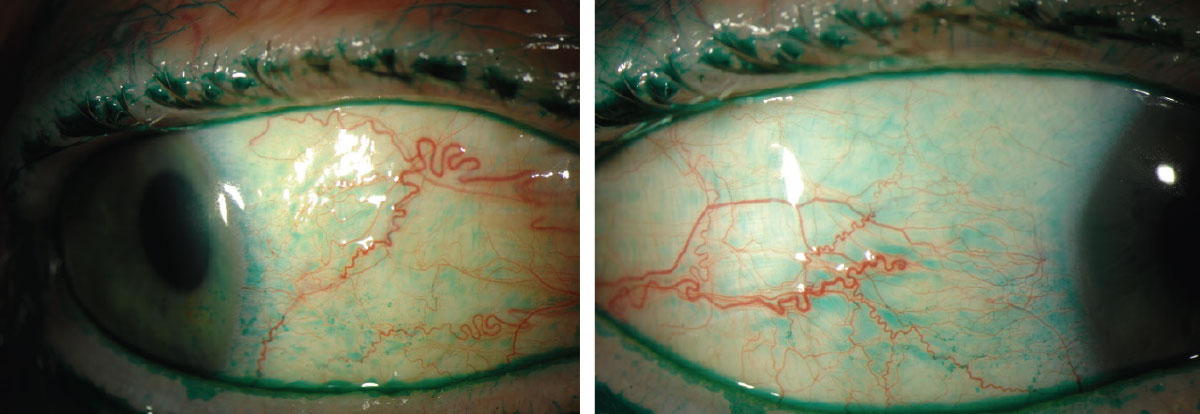

| Lissamine green staining on the conjunctiva reveals signs of dry eye. Photos: Michelle Hessen, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Strike a Better Balance

The consumption of omega-6 fatty acids is at an all-time high, and nutritionists are recommending not only an increase in dietary omega-3 but also a decrease in omega-6 intake to more efficiently balance the ratio. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics suggests consuming at least 500mg of EPA/DHA per day (200mg more per day for pregnant or lactating females) and the American Heart Association recommends 1,000mg per day for those with coronary heart disease.36

Dietary intake. The most effective way to increase omega-3 through diet is by consuming non-fried cold-water fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, tuna or sardines two to four times per week. Marine sources that contain EPA and DHA are preferred over flax, hemp and chia due to the limited conversion of ALA in the human body. Choosing grass-fed over grain-fed meat sources will also increase omega-3 intake.12,36 Numerous brands of eggs, yogurt, juices and milk are fortified with omega-3 and notably, infant formulas have been fortified with DHA since 2002.12

Minimal omega-6 is required for normal metabolic function, and necessary amounts are easily obtained by regular consumption of healthful sources such as olive oil, avocados and nuts (including nut butters). Efforts should be focused on decreasing unhealthful sources, primarily vegetable oils. Avoiding corn, soybean, peanut and sunflower oils and instead opting for olive oil, coconut oil or butter when cooking is beneficial. Finally, nutritionists recommend limiting the use of products that contain high amounts of vegetable oils and omega-6 such as salad dressing, mayonnaise and margarine.37 The Institute of Medicine recommends that calories from omega-6 fats should comprise 5% to 10% of your daily caloric intake.

Supplementation. Nutritional supplements are certainly beneficial in increasing consumption of essential fatty acids, and myriad options are available to patients. However, dosages and fatty acid sources vary significantly between products, and there is currently no FDA-approved formulation.31,38

Algal oil supplements are an excellent source of omega-3 for vegetarians who do not consume fish products and prefer to avoid marine sourced supplements.37

Without a clear consensus on the use of omega fatty acids in the management of dry eye, finding the right management path can seem daunting. Eye care providers can begin by discussing diet and nutrition with all of their patients, particularly those suffering from dry eye. Provide information on the recommended daily intakes of omega-3 as well as the dietary choices patients can make to increase omega-3 and decrease omega-6 to skew the ratio in a more healthful direction. The impact of omega-3 and a balanced omega-3/omega-6 ratio on systemic inflammatory and chronic conditions is well supported by validated research, and the benefit of making better nutritional choices is clear.

Inflammation plays a prominent role in DED, and it is rational to continue exploring the use of omega fatty acids in its management. But more controlled large-scale studies with standardized outcomes are necessary to clarify exactly what role essential fatty acids and the omega-6/omega-3 ratio play in the treatment and prevention of dry eye. We as practitioners must stay apprised to ensure we are practicing good evidence-based medicine for our patients.

Dr. Sanford is an attending optometrist at the Memphis VA Medical Center.

1. Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56:365-79. 2. American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel. Preferred practice pattern guidelines: dry eye syndrome. Academy of Ophthalmology. November 2018. 3. Paulsen AJ, Cruickshanks KJ, Fisher ME. Dry eye in the beaver dam offspring study: prevalence, risk factors, and health-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(4):799-806. 4. Galor A, Feuer W, Lee D. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye syndrome in a United States Veterans Affairs population. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152: 377-84. 5. Craig TP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocular Surf. 2017;15(3):276-83. 6. Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocular Surf. 2017;15(3):334-65. 7. Wei Y, Asbell P. The core mechanism of dry eye disease (DED) is inflammation. Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40(4):248-56. 8. Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea. 2011;30(4):379-87. 9. Asbell PA, Maguire MG, Pistilli M. n-3 Fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of dry eye disease. New Eng J Med. 2018;378:1681-90. 10. Kangari H, Eftekhari MH, Sardari S. Short-term consumption of oral omega-3 and dry eye syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(11):2191-96. 11. Daley CA, Abbott A, Doyle PS. A review of fatty acid profiles and antioxidant content in grass-fed and grain-fed beef. Nutrition J. 2010;9:10. 12. National Institutes of Health. Omega-3 fatty acids fact sheet for healthy professionals. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional. October 17, 2019. Accessed march 24, 2020. 13. Chee KM, Gong JX, Rees DM. Fatty acid content of marine oil capsules. Lipids. 1990;25(9):523-28. 14. Giannaccare G, Pellegrini M, Sebastini S. Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for treatment of dry eye disease: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Cornea. 2019;38(5): 565-73. 15. Hom MM, Asbell P, Barry B. Omegas and dry eye: more knowledge, more questions. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92:948-56. 16. Blasblag TL, Hibbeln JR, Ramsden CE. Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:950-62. 17. Silva JR, Burger B, Kuhl CM, Candreva T. Wound healing and omega-6 fatty acids: from inflammation to repair. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2503950. [Epub]. 18. Kokke KH, Morris JA, Lawrenson JG. Oral omega-6 essential fatty acid treatment in contact lens associated dry eye. Cont Lens Ant Eye. 2008;31:141-46. 19. Sheppard JD, Singh R, McClellan AJ. Long term supplementation with n-6 and n-3 pufas improves moderate to severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca: a randomized double blind clinical trial. Cornea. 2013;32(10):1297-1304. 20. Vasquez A. Reducing pain and inflammation naturally. Part II: new insights into fatty acid supplementation and its effect on eicosanoid production and genetic expression. Nutritional Perspectives: J Counc Nutr Am Chiro Assoc. 2005;28(1):5-16. 21. Brignole-Baudouin F, Fauduoin C, Aragona P. A multicentre, double-masked, randomized, controlled trial assessing the effect of oral supplementation of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on a conjunctival inflammatory marker in dry eye patients. Acta ophthalmol. 2011;89:591-97. 22. Calder P. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am J Clin Nutrition. 2006;83(6):1505-19. 23. DiNicolantonio JJ, O’Keefe JH. Importance of maintaining a low omega-6/omega-3 ratio for reducing inflammation. Open Heart. 2018;e000946. 24. Miljanovic B, Trivedi KA, Dana MR. Relation between dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and clinically diagnosed dry eye syndrome in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:887-93. 25. Simopoulos AP. Evolutionary aspects of diet, the omeg-6/omega-3 ratio and genetic variation: nutritional implication for chronic diseases. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:502-07. 26. Russo GL. Dietary n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: From biochemistry to clinical implications in cardiovascular prevention. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:937-46. 27. Liu Y, Kam WR, Sullivan DA. Influence of omega 3 and 6 fatty acids on human meibomian gland epithelial cells. Cornea. 2016; 35(8):1122-26. 28. Li K, Huang T, Zheng J. Effect of marine derived n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on C-reactive protein, interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha: a meta- analysis. PLoS One 2014; 9:e88103. 29. Simopoulos AP. Omega 3 fatty acids in in health and disease and in growth and development. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:438-63. 30. Wojtowicz JC, Butovich I, Uchiyama E. Pilot, prospective, randomized, double masked, placebo controlled clinical trial of an omega-3 supplement for dry eye. Cornea. 2011;30(3):308-14. 31. Bhargava R, Kumar P. Oral omega-e fatty acid treatment for dry eye in contact lens wearers. Cornea. 2015;34(4):413-20. 32. Bhargava R, Kumar P, Kumar M. A randomized controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids in dry eye syndrome. Int J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(6):811-16. 33. Deinema LA, Vingrys AJ, Wong CY. A randomized, double masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of two forms of omega-3 supplements for treating dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:43-52. 34. Epitropoulos AT, Donnenfield ED, Shah ZA. Effect of oral re-esterified omega-3 nutritional supplementation on dry eyes. Cornea. 2016;35(9):1185-91. 35. Asbell PA, Maguire MG. Why DREAM should make you think twice about recommending omega-3 supplements. Ocular Surf. 2019;17:617-18. 36. Vannice G, Rasmussen H. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: dietary fatty acids for healthy adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(1):136-53. 37. Jacobs A. Balancing Act. Today’s Dietitian. 2013;15(4):38. 38. Rand AL, Asbell PA. Current opinion in ophthalmology nutritional supplements for dry eye syndrome. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(4):279-82. 39. Vasquez A. Reducing pain and inflammation naturally. part 1: new insights into fatty acid biochemistry and the influence of diet. Nutritional Perspectives. 2004;Oct:5,7-10,12,14. |