|  |

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the leading cause of blindness in the United States among working age adults and the most common disease to require a vitrectomy.1 While careful management can delay, or even eliminate, the need for a vitrectomy, in our experience, the majority with catastrophic vision loss present with little to no history of routine eye care. Even with diligent follow-up, some diabetic patients progress rapidly.

When to Refer

Most optometrists are comfortable with routine DR evaluations in mild to moderate cases. But the longer a patient has diabetes, and especially with a lack of blood sugar control, the greater the suspicion that they may develop more advanced DR. And when damage becomes severe—beyond primary diabetic macular edema (DME)—patients may need surgical intervention. The indications for pars plana vitrectomy are far more serious than primary DME and will require immediate referral. These indications include: vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment, pre-macular hemorrhage and DME caused by traction.

|

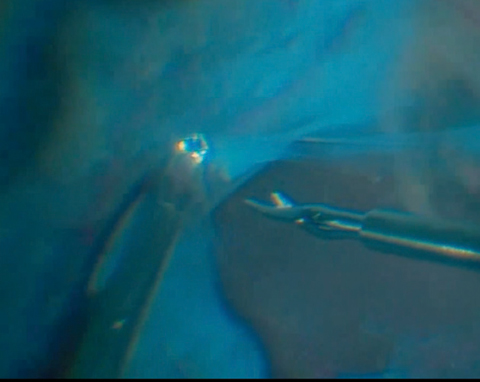

| The surgeon first uses forceps and scissors to separate the membranes. |

|

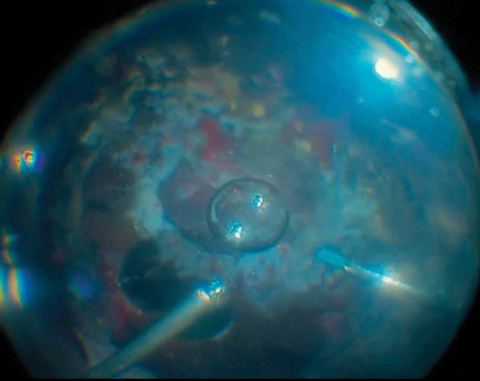

| At the conclusion of the surgery, the surgeon adds air and silicone oil. |

Repairing the Retina

Patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy who suffer from a tractional retinal detachment may need specialized surgical intervention.

The resulting inflammation and bleeding within the retina and subretinal space lead to excessive scaring in both the retina and vitreous. Removing this scar tissue becomes the challenge and is often the main variable for success. Removal begins with bimanual forceps and scissors to separate and access underneath the fibrous membranes. The surgeon then removes the membranes using a beveled vitrectomy instrument that can cut up to 10,000 times per minute. Next, a laser can help tack down any retinal tears or breaks and even prophylactically treat areas at risk or were under traction. The surgery usually concludes with an air/fluid exchange or placement of silicone oil in the vitreous cavity.

New ToolsWith new 25-gauge and 27-gauge retinal surgeries, specialists can more precisely dissect retinal tissue and cause fewer complications. These smaller instruments typically remove tissue efficiently, 25-gauge better than 27-gauge, so size does matter. In addition, both can cut through relatively thick fibrotic membranes. |

Post-op Complications

Surgeons always attempt to minimize postoperative inflammation, but other complications include: elevated IOP, cataract formation, rubeosis and neovascular glaucoma, postoperative vitreous hemorrhage, anterior hyaloidal fibrovascular proliferation and retinal redetachment.

Comanaging optometrists can manage elevated IOP with aqueous suppressants, not prostaglandins due to risk of further inflammation. If a patient develops cataracts, clinicians can monitor for progression and visual significance. All other complications should be referred back to the retinal surgeon for evaluation.

Because these eyes have poor inflammation control, which led to the initial surgery, it is not uncommon for post-surgical complications or further pathology progression.

Dr. Franklin practices at the Diagnostic & Medical Clinic in Mobile, AL.

| 1. Spraul CW, Grossniklaus, HE. Vitreous Hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;42:3-39. |