History

A 57-year-old black female presented emergently with a chief complaint of painful vision loss in her right eye. The patient explained that she had previously experienced similar episodes in both eyes, but never this severe. She said that, in the past, the episodes always resolved without any treatment. The patient had no documented history of ocular injury or glaucoma. Her systemic history was significant for hypertension, which was properly controlled with hydrochlorothiazide. She reported no known allergies, but reported recently undergoing laboratory work for suspected autoimmune disease.  |

| Our patient complained of painful vision loss in her right eye.

What’s the diagnosis? |

Discussion

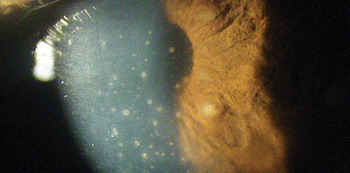

Additional testing included a thorough review of the patient’s systemic history, including queries about arthritis, rashes, shortness of breath, swollen lymph nodes, headaches, insect bites, recent travel and sexually transmitted diseases. Laboratory studies included a complete blood count with differential and platelets, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody panel, reactive plasma regain, venereal disease research lab, angiotensin converting enzyme, human leukocyte antigen test, purified protein derivative, chest x-ray, Lyme titer, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test and mono-hema agglutination for treponemal palladium.The diagnosis in this case is granulomatous iritis with busacca nodules secondary to the recent development of sarcoidosis. Her internist confirmed the diagnosis based upon the lab testing results. Granulomatous iritis typically is caused by an underlying systemic disease. In this case, our patient was diagnosed with sarcoidosis––an auto-immune disorder that affects 15 in 100,000 Americans per year.1 Sarcoidosis may involve any organ in the body; however, the condition most commonly impacts the lungs, lymph nodes, eyes and skin.1 The presentation of systemic sarcoidosis can be mild to severe.1 Although the fundamental cause is unknown, research published in 2006 indicates a possible immunogenetic predisposition.1 Sarcoidosis symptoms typically include cough, shortness of breath, fever, fatigue, weight loss, small red bumps and arthritis.1-3 Generally speaking, sarcoid patients’ immune systems overreact to particles that enter the body during normal respiration.1-3 T-helper lymphocytes respond to this perceived threat, and precipitate the development of inflammatory cell deposits (non-necrotizing granulomas).1-3

The condition more frequently presents in females than males, and is more likely to occur in blacks than whites.4 Further, sarcoidosis usually is initially detected and diagnosed between ages 20 and 40.1,4 The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be confirmed via chest x-ray, pulmonary function test, gallium scan, angiotensin-converting enzyme test or nonspecific nodule biopsy.3,5-8 Uveitis is the most common ocular manifestation of sarcoidosis.2 In the eye, clinical symptoms begin with hazy vision, pain, lacrimation and photophobia.7 In most instances, these ocular symptoms present bilaterally. If the cornea becomes coated with keratic precipitate (cellular debris) or the posterior segment becomes involved, patients also may experience floaters and decreased vision. Clinical signs include increased intraocular pressure (IOP), enlarged lacrimal glands, redness of the bulbar conjunctiva, keratic precipitates and possible corneal edema, and cells and flare in the anterior chamber.3,7,9,10

Additionally, anterior and posterior synchiae may be found on the iris.7,8 In our patient, we found busacca nodules (an accumulation of inflammatory cells) on the surface of both irides. This finding confirms the condition’s granulomatous nature. In comparison, smaller koeppe nodules located on the pupillary border may be seen in both granulomatous and nongranulomatous irides.7,8 Posterior segment involvement occurs in approximately one third of patients with ocular sarcoidosis, and typically presents as an intermediate uveitis.3,7,8 Peripheral neovascularization, with or without vitreous hemorrhage, also is possible.5 Further, sarcoid patients may develop cystoid macular edema, multifocal choroiditis and retinal granulomas.5 Under these circumstances, visual outcomes may vary tremendously. The visual prognosis is far worse for patients with multifocal choroditis or panuveitis.11 Fortunately, our patient manifested no posterior involvement.

Common treatment for granulomatous iritis includes cycloplegia to relieve pain and break synechiae, and topical corticosteroids to reduce inflammation.1,2,9 If topical treatment fails, either oral administration or periocular injection of corticosteroids may be warranted––especially if there is posterior segment involvement.2 In worst-case scenarios, surgical intervention (e.g., pars plana vitrectomy or iris granuloma excision) is necessary.2

Patients who are diagnosed with sarcoidosis should be scheduled for frequent follow-up examinations to ensure that subclinical ocular inflammation is detected and that IOP is not increasing secondary to anti-inflammatory therapy. Semi-annual visits are reasonable for uncomplicated, well-controlled cases. However, patients who experience systemic/ocular disease fluctuation or increased IOP should be scheduled for quarterly follow-up. IOP measurements are a necessity for patients who use topical, oral or inhaled steroids.1 If IOP becomes significantly elevated, topical aqueous suppressants such as timolol can be used while continuing the anti-inflammatory agent. The prostaglandin analogs (PGAs) are not ideal because their chemistry is similar to the body’s prostaglandin chemoattractants. Therefore, these agents may actually instigate or further exacerbate inflammation. Further, PGAs are often slow to work, requiring several weeks of dosing to achieve maximal pressure reduction. We promptly treated our patient with 1% atropine BID and 1% prednisolone acetate QH with an eventual taper. Follow-up examinations were scheduled once a week for the first three weeks, then once a month until the ocular symptoms resolved completely. After one month, her vision returned to normal. We will continue to monitor the patient every four months until the IOP and systemic inflammation are stable. Depending upon her management course and overall stability, we will slowly extend the intervals between follow-up evaluations.

Thanks to Monica Ma, OD, of Burlington, NC, for her contributions to this case.

1. Weisinger HS, Steinfort D, Zimmet AD, et al. Sarcoidosis: case report and review. Clin Exp Optom. 2006 Nov;89(6):361-7. 2. Ocampo VV Jr, Foster CS, Baltatzis S. Surgical excision of iris nodules in the management of sarcoid uveitis. Ophthalmology. 2001 Jul;108(7):1296-9. 3. Ohara K, Okubo A, Kamata K, et al. Transbronchial lung biopsy in the diagnosis of suspected ocular sarcoidosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1993 May;111(5):642-4. 4. Bonfioli AA, Orefice F. Sarcoidosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005 Jul-Sep;20(3):177-82. 5. Jordan DR, Anderson RL, Nerad JA, Scrafford DB. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1988 Aug;23(5):203-7. 6. Power WJ, Neves RA, Rodriguez A, et al. The value of combined serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and gallium scan in diagnosing ocular sarcoidosis. Ophthalmology 1995 Dec;102(12):2007-11. 7. Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the firstInternational Workshop On Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009 May-Jun;17(3):160-9. 8. Kawaguchi T, Hanada A, Horie S, et al. Evaluation of characteristic ocular signs and systemic investigations in ocular sarcoidosis patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2007 Mar-Apr;51(2):121-6. 9. Ohara K, Okubo A, Sasaki H, Kamata K. Intraocular manifestations of systemic sarcoidosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1992;36(4):452-7. 10. Lauby TJ. Presumed Ocular Sarcoidosis. Optometry 2004 May;75(5):297-304. 11. Lobo A, Barton K, Minassian D, et al. Visual loss in sarcoid-related uveitis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2003 Aug;31(4):310-6.