The term “low vision” refers to vision loss that is uncorrectable with current medical and surgical interventions or using traditional spectacle and contact lenses.1,2 While the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recognize distinct categories of low vision based primarily on best-corrected visual acuity (VA), a much broader range of patients may also be defined as having “low vision” based on compromised visual fields, impaired contrast sensitivity, or other deficits in visual function.3

The practice modality known as vision rehabilitation involves development of an individual rehabilitation plan (IRP) to help care for the patient with low vision. According to the American Optometric Association, an IRP may include “prescription glasses or contact lenses, optical and electronic magnification devices, assistive technology, glare control with therapeutic filters, contrast enhancement, eccentric viewing, visual field enhancement, non-optical options and referral for additional services with other professionals.”2

A 2017 analysis estimated that 7.08 million people in the United States were living with uncorrectable VA loss.4 The same study indicated that 1.08 million of these individuals demonstrated VA loss that qualified them to meet the federal definition of “legal blindness.”4,5 When considering the other deficits in visual function that could convey “low vision” or “legal blindness” status, these numbers grow larger yet. Projections estimate the number of legally blind individuals will double by the year 2050, due in large part to the prevalence of age-related eye disease and the general aging of the US population.6

Our optometric training and scope of practice makes us the ideal providers of vision rehabilitation care. We are well-equipped to combine our understanding of optics with our knowledge of ophthalmic diseases and their functional implications to effectively serve the visually impaired patients in our practices. However, for those of us outside of academic and not-for-profit practice settings, it may be difficult to tackle IRP development and provide comprehensive vision rehabilitation care. For this reason, it is important to discuss the ways in which all practicing optometrists can readily incorporate some foundational vision rehabilitation components into their practice to better serve this growing patient population.

Levels of Vision Rehabilitation

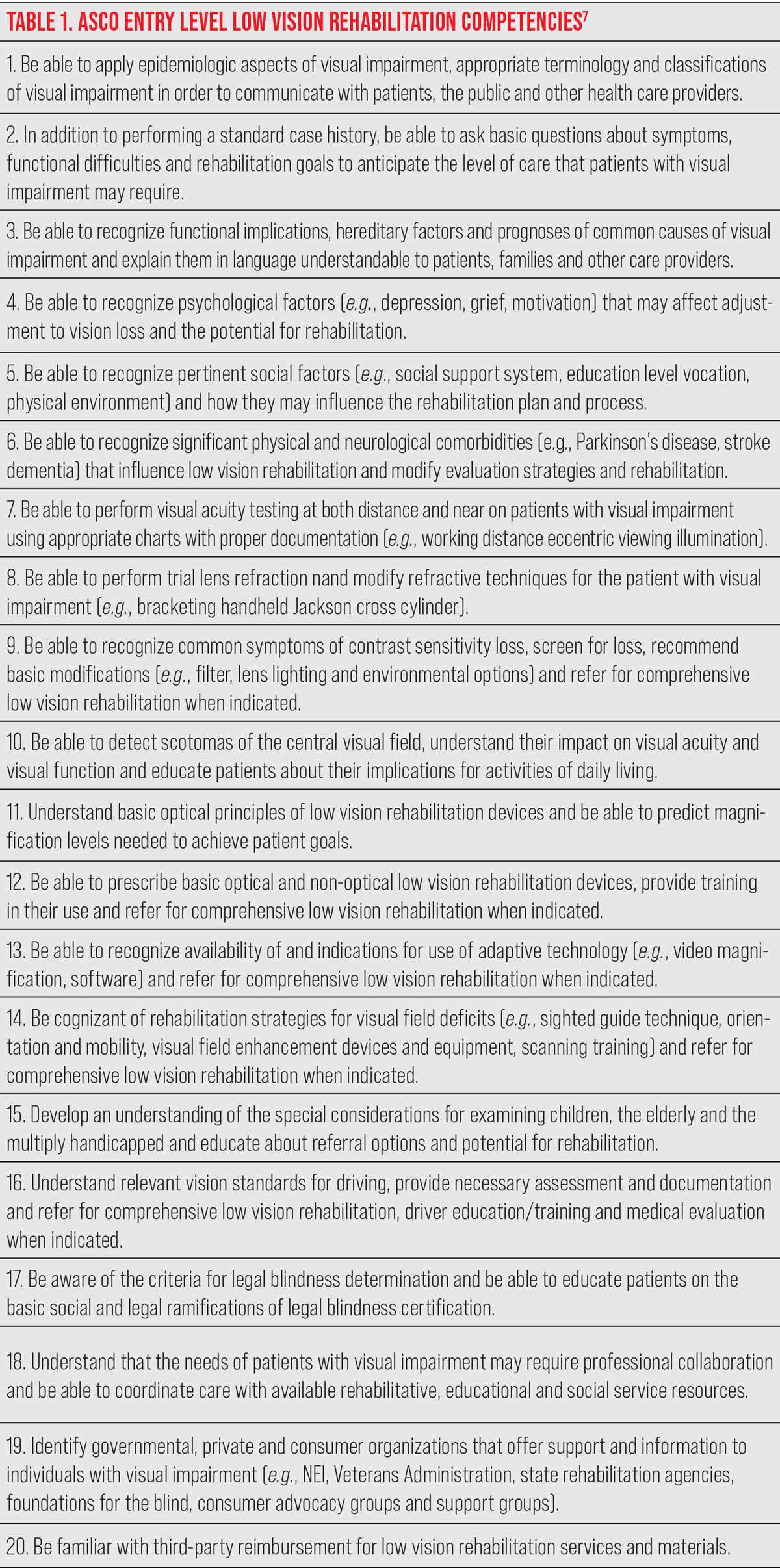

In 2010, the Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry (ASCO) convened a working group of optometric vision rehabilitation educators from across the country to define and delineate tiered competencies for vision rehabilitation care among graduates from schools and colleges of optometry.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

The result of this group’s work is summarized in Table 1, which clearly lays out 20 entry-level competencies for vision rehabilitation care that can be expected of any practicing optometrist regardless of their practice setting.7 It is valuable to review each of the points laid out in Table 1 and elaborate on the ways in which these can be applied in most optometric practices.

Patient History Competencies

The first of the 20 ASCO competencies shown in Table 1 has to do with the foundational knowledge of epidemiology and vision impairment we all obtain through our strong optometric education and ongoing continuing education efforts.7 Our understanding of, and ability to communicate, these basic principles are rightfully at the top of the ASCO list of entry level competencies.

Competency number two requires that the optometrist obtain a thorough case history. A comprehensive understanding of a visually impaired patient’s rehabilitative needs requires a case history that goes beyond that of a routine eye exam and dives into specific functional difficulties caused by one’s vision loss, goals and expectations for the vision rehabilitation process.

While the exact set of intake questions used may vary from clinic to clinic, the National Eye Institute’s Visual Functioning Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25) provides a solid bank of foundational questions from which to adapt an intake questionnaire for visually impaired patients.8 Listening when patients voice functional concerns relative to their vision loss, along with asking the appropriate questions to elicit functional concerns when needed, are foundational to the development of an effective IRP.

The next four ASCO competencies describe the ability to recognize various patient-specific factors that may influence the vision rehabilitation process. These include familial, psychological and social factors as well as physical and neurologic comorbidities that may impact an IRP. Recognition of these factors may take place during the case history discussion or at any time throughout the vision rehabilitation evaluation.

If appreciation for any of these factors seems to fall outside of what we all took from our optometric education, Faye’s Clinical Low Vision (2nd Ed.) remains a proven and useful resource.9

|

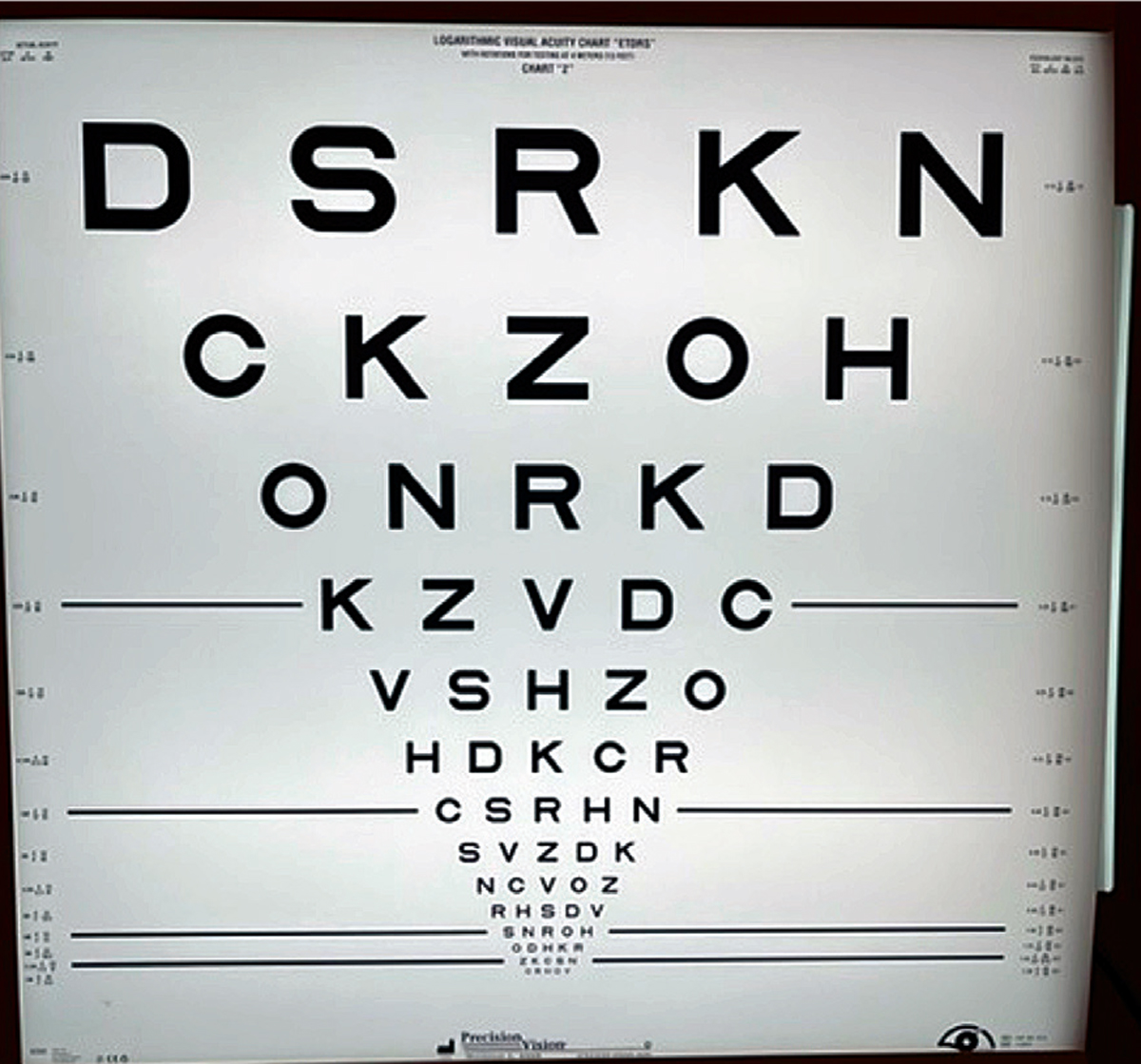

| Fig. 1. The ETDRS logMAR chart can measure VA at distance. Click image to enlarge. |

Assessment Competencies

Competency number seven begins the actual vision examination process, detailing a thorough measurement of VA at distance and near. Depending on the practice setting and some patient-specific factors, various VA charts may be used. For distance VA measurement, a stand-based Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS; Precision Vision) chart remains the gold standard (Figure 1).10

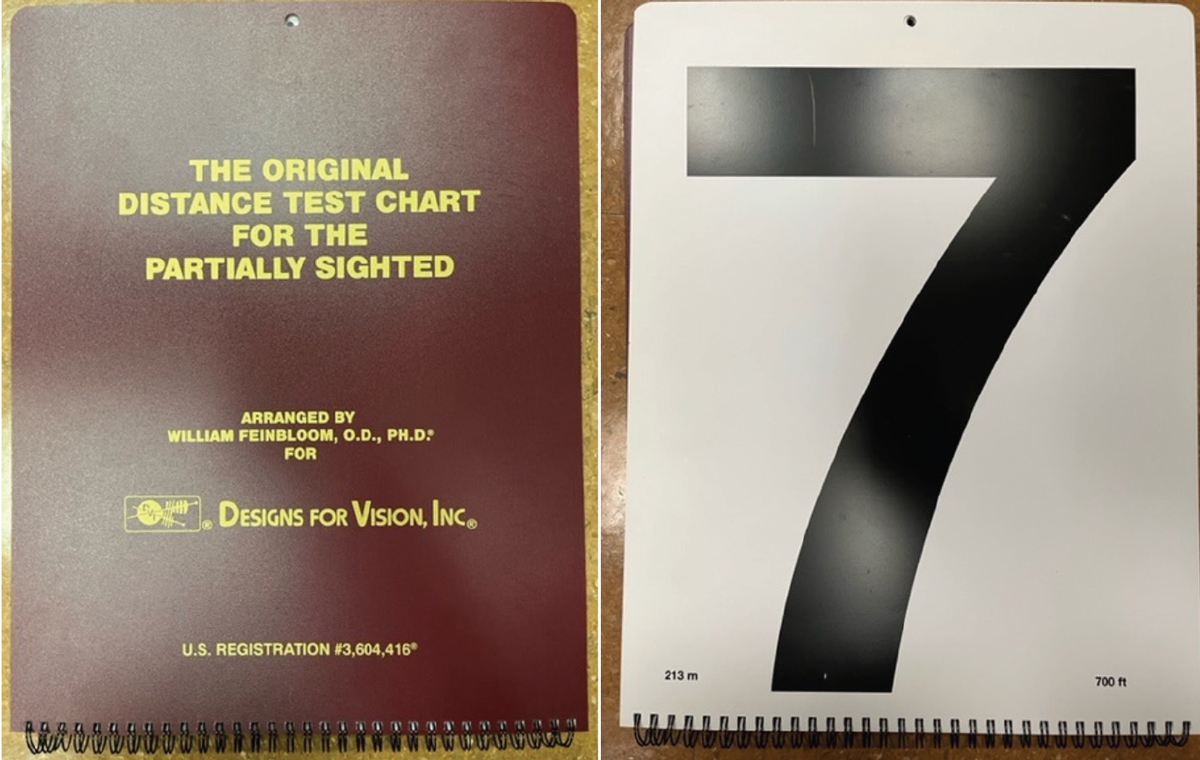

This chart is mobile and conveniently allows for adjustment of the patient-to-target distance in cases when a patient is unable to read the largest optotypes from the standard 4m viewing distance. The backlit version also eliminates the need to provide proper illumination of the surface of the chart. A useful alternative distance VA chart is the William Feinbloom Distance Test Chart for the Partially Sighted (Designs for Vision; Figure 2). In employing this option, it is important to use and document appropriate illumination of the target.

|

|

Fig. 2. The Feinbloom Distance Test Chart for the Partially Sighted. Click image to enlarge. |

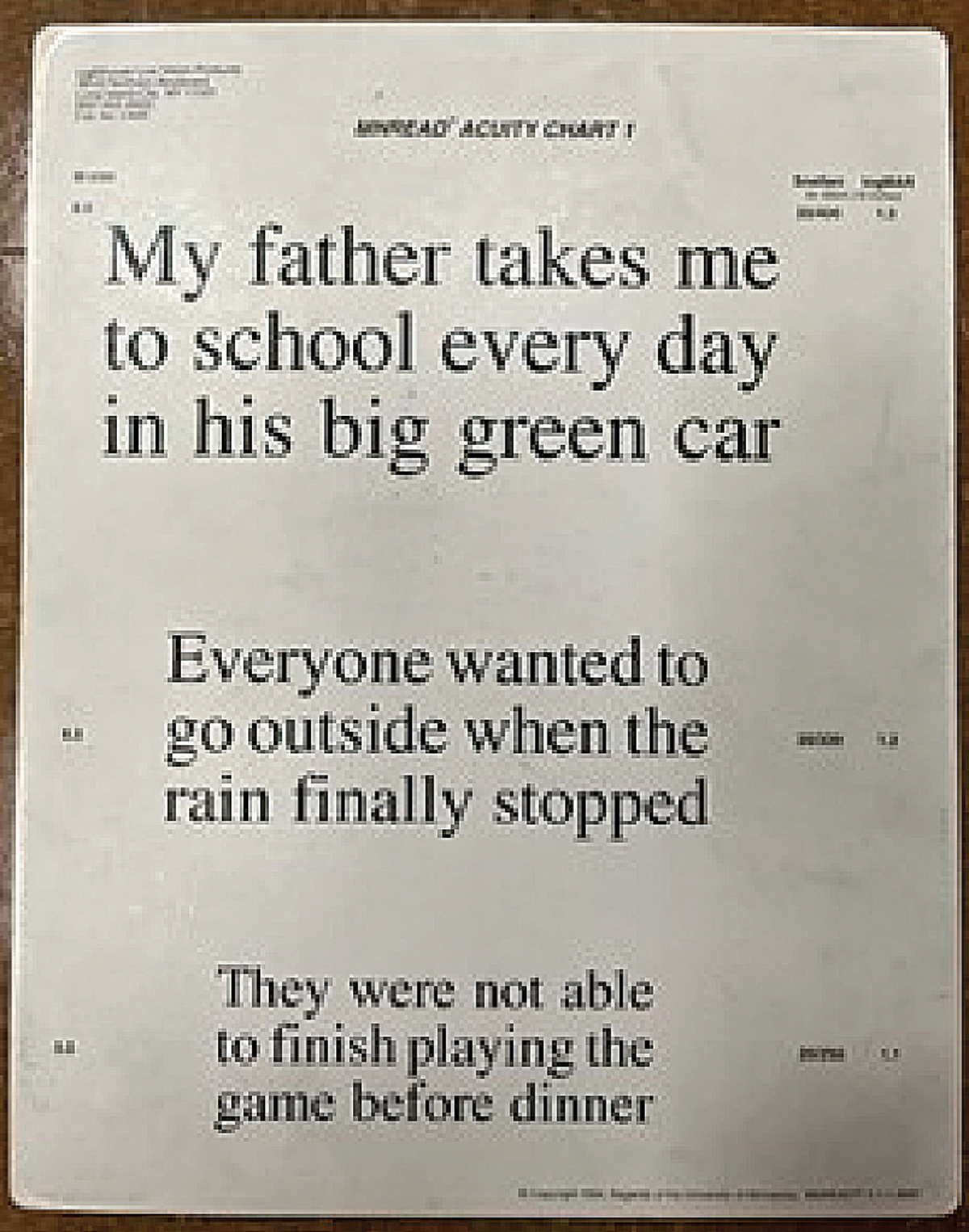

For measuring near VA, various options exist that use single letters/numbers, words or continuous text. One of the more commonly used continuous text options is the MNRead Reading Test ((Lighthouse Low Vision Products; Figure 3).11 Regardless of the chart being used, documenting distance and near VA is completed in standard form of “testing distance/optotype size” in a common (metric or imperial) measurement, always noting eccentric view (if employed) and lighting used (where pertinent).

A careful trial frame refraction, described in competency number eight, dictates everything that comes thereafter in a vision rehabilitation evaluation. This type of refraction is not all that different from the expert phoropter refractions being performed on our patients on a daily basis. The main difference lies in the use of a trial frame, loose lenses and a handheld Jackson cross cylinder (JCC) lens, which simplify the refraction of a patient who uses an eccentric view or atypical head posture to reach a null point and dampen nystagmus.

|

|

Fig. 3. The MNRead Continuous Text Acuity Chart can help measure VA at near. Click image to enlarge. |

Further, the trial frame and loose lenses allow for larger and more efficient jumps in lens power when a patient’s acuity dictates a larger “just noticeable difference” in lens power be demonstrated. Otherwise, the trial frame refraction uses the same order of spherocylindrical lens power refinement steps and bracketing technique as a refraction in the phoropter. The goal of the trial frame refraction is the same as any other refraction we perform: to optimize a patient’s visual clarity through correction of ametropia.

Competency number nine pertains to contrast sensitivity (CS), a measure of visual function that is often reduced in the visually impaired patient and is likely not a primary focus in most routine eye care settings. Formal clinical testing of contrast sensitivity is simple and may be completed with any number of validated clinical tests. The Pelli-Robson CS Chart and Mars Letter Contrast Sensitivity Test are two common options for efficiently testing CS. The practicing optometrist should be comfortable recognizing and screening for contrast sensitivity limitations, potentially using one of the aforementioned tests, and should also be able to recommend simple modifications (filters and environmental lighting) to aid in these patients’ function. If not, they should be prepared to make a referral to a comprehensive vision rehabilitation program.

Another important visual function consideration is the recognition of, and modifications to account for, scotomas. Many patients needing vision rehabilitation care have central visual deficits from commonly encountered conditions such as age-related macular degeneration, various inherited macular dystrophies, retinal vascular occlusions and some optic nerve disorders. Presence of scotomas may be detected through knowledge of a patient’s diagnosis, responses during the intake interview, or formal tests such as microperimetry or the California Central Field Test.

Competency number 10 states that the optometrist should be able to detect scotomas and educate the patient on their presence and strategies, such as eccentric viewing, for working around them. Again, if they are unable to do so, referral to a comprehensive vision rehabilitation program should be initiated.

Treatment Competencies

A comprehensive understanding of optics is foundational to our optometric education and to competency number 11. Being able to predict magnification needs based on a patient’s visual function and goals and understanding the angular magnification properties of various devices used in vision rehabilitation are considered entry-level competencies.

For example, using a ratio of the target print size to the currently legible print size helps to determine the dioptric power needed to reach the target print size. This can predict the appropriate handheld or spectacle-based tools for a given patient and guide the optometrist’s handling of the device demonstration, prescription and training process.

In general, one should be comfortable prescribing near reading add powers up to around six diopters and accounting for the corresponding convergence demand through the appropriate amount of base in prism. Otherwise, referral for comprehensive vision rehabilitation is indicated.

Basic vision rehabilitation device prescription and training are the focus of point number 12. The optometrist should be equipped to demonstrate low-powered optical magnification devices and non-optical devices such as lighting options and filters. If they choose not to perform these demonstrations, referral to a comprehensive vision rehabilitation program is the standard.

Recognition of pertinent assistive technology options for a given patient is an important part of developing an IRP. Standalone desktop and portable video-based magnifiers, as well as the mobile phone and tablet devices already owned by many of our patients, are examples of helpful assistive technology options that can benefit our visually impaired patients. Competency number 13 notes that it is adequate to recognize the need for, and refer to, appropriate assistive technology training programs when indicated.

When a patient’s visual impairment entails visual field compromise, the optometrist should be comfortable recognizing its impact on patient function and addressing this appropriately. As outlined in competency number 14, this may include prescription of devices that enhance visual field awareness (e.g., prisms, reverse telescopes) or referral for appropriate training such as sighted guide and formal orientation and mobility programs.

Just as in primary optometric care, the practitioner is likely to encounter children and people with multiple disabilities among their visually impaired patient base. Competency number 15 notes that the optometrist should be comfortable employing specialized examination techniques and making appropriate referral for services and training in these cases, when indicated.

Competencies number 16 and 17 stress the importance of knowing legal blindness and licensure laws to better serve visually impaired patients and to provide documentation or referral for additional training or services as needed. A refresher on legal blindness criteria can be found on the Social Security Administration’s website, while state-by-state vision testing standards for licensure are kept up to date by Prevent Blindness on their website.5,12

Competency points 18 and 19 pertain to the multidisciplinary nature of comprehensive vision rehabilitation care. The optometrist should know when to include referral to other rehabilitation professionals and social or psychological support services in a patient’s IRP. Further, connecting a patient with the appropriate governmental or community support networks can be an important part in helping to meet that patient’s individual needs.

The American Printing House for the Blind, the National Federation of the Blind and the American Foundation for the Blind all maintain helpful online directories of available vision rehabilitation resources in one’s state or region.13-15

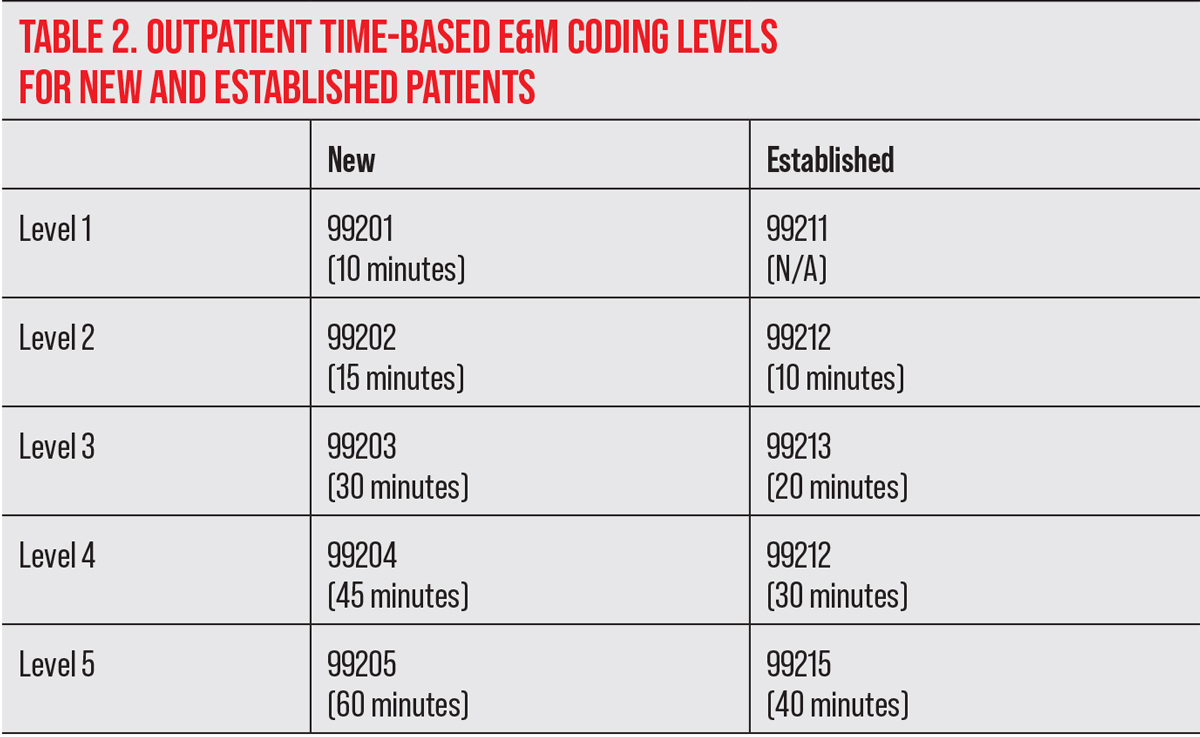

Finally, competency point number 20 pertains to one’s understanding of vision rehabilitation billing, coding and reimbursement structures. These factors likely play a role in limiting the number of private practice optometrists providing entry level vision rehabilitation services, but it doesn’t have to be that way. The practicing optometrist should understand that vision rehabilitation billing is typically based on time spent and uses the Evaluation & Management (E&M, 99xxx) codes.

The time spent includes any face-to-face time with the patient, as well as time spent on the same day preparing for the case and documenting findings or communicating with other professionals regarding the case. It does not include the refraction or other diagnostic testing that are being billed as separate services.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Table 2 lays out time requirements for billing each E&M code for both new and established outpatients. Any additional time spent beyond the Level 5 allotment in each column can be billed in additional 15-minute increments using code 99417. The ability to bill visits based on time can help to offset the inherent reduction in patient volumes when providing vision rehabilitation care in a private practice setting.

As for the prescription of vision rehabilitation devices, it should be noted that most are not covered as durable medical equipment by Medicare and other medical insurance carriers. While we are hopeful that this will change in the coming years, it is important for the vision rehabilitation practitioner to be able to tap into other coverage options for these devices. Options may include state blind or vocational rehabilitation services, private grant opportunities, flexible spending accounts or other local funding resources.

Clinical Takeaways

Caring for visually impaired patients falls squarely in optometry’s wheelhouse. Our comprehensive understanding of both ophthalmic disease and optics puts us all in a position to help our visually impaired patients to maximize their quality of life.

As the prevalence of vision impairment continues to grow, provision of vision rehabilitation services will fall to optometrists in all practice settings.6 While not all of us are equipped to provide comprehensive vision rehabilitation services, the core competencies defined by the ASCO provide a road map to starting the vision rehabilitation process for patients who need it.7

As was noted in the preceding discussion of all 20 ASCO competencies, there will come a point in many vision rehabilitation cases where referral for more comprehensive services is indicated. This may be dictated by the need for near add powers above a certain threshold, prescription a bioptic telescope, eccentric viewing training, or referral for vocational rehabilitation, among many other factors.

When the needs of the patient are simpler, private practice optometrists can use the ASCO competencies to enhance their care for this growing, and grateful, patient population.

In summary, it’s important to view vision rehab as a spectrum of interventions—many of which are accessible to primary care optometrists—rather than a binary choice that forces ODs to be “all-in” or “all-out.”

1. Turbet D, Gudgel D. What is low vision? American Academy of Ophthalmology. www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/low-vision. September 23, 2021. Accessed March 2, 2022. 2. Low vision and vision rehabilitation. American Optometric Association. www.aoa.org/healthy-eyes/caring-for-your-eyes/low-vision-and-vision-rehab?sso=y. Accessed March 2, 2022. 3. ICD-10-CM/PCS MS-DRG v37.0 Definitions Manual. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. www.cms.gov/icd10m/version37-fullcode-cms/fullcode_cms/P0427.html. Accessed March 2, 2022. 4. Flaxman AD, Wittenborn JS, Robalik T, et al. Prevalence of visual acuity loss or blindness in theUS: a Bayesian meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(7):717-23. 5. Disability evaluation under social security. Social Security Administration. www.ssa.gov/disability/professionals/bluebook/2.00-SpecialSensesandSpeech-Adult.htm. Accessed March 2, 2022. 6. Varma R, Vajaranant TS, Burkemper B, et al. Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(7):802-9. 7. Kammer RL et al. The development of entry level low vision rehabilitation competencies in optometric education. Optom Ed. 2010;35(3):98-107. 8. Visual Function Questionnaire 25. National Eye Institute. www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/resources-for-health-educators/outreach-materials/visual-function-questionnaire-25. Accessed March 2, 2022. 9. Faye EE. Clinical Low Vision (2nd Ed). Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1984. 10. Shamir RR, Friedman Y, Joskowicz L, et al. Comparison of Snellen and Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study charts using a computer simulation. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(1):119-23. 11. Brussee T, van Nispen RM, van Rens GH. Measurement properties of continuous text reading performance tests. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 2014;34(6):636-57. 12. Prevent Blindness. State vision screening and standards for license to drive. lowvision.preventblindness.org/2003/06/06/state-vision-screening-and-standards-for-license-to-drive/#top. Updated April 2020. Accessed March 2, 2022. 13. Low vision services: APH directory of services listings. Vision Aware. visionaware.org/directory/results/?CategoryID=66. Accessed March 2, 2022. 14. National Federation of the Blind. nfb.org. Accessed March 2, 2022. 15. American Foundation for the Blind. afb.org. Accessed March 2, 2022. |