|

If you can measure it, then you must prescribe it.

This is an aphorism that has been drilled into us since early on in our optometric careers. Correcting refractive error by prescribing from our findings seemed quite easy at first. All we needed to do was spend time upfront splitting hairs to get the axis just right and confirm that 0.25 difference between the spheres in both eyes. Then, we could take pride in writing an “accurate” prescription.

Why not just stop there and save ourselves the trouble and confusion that comes with finding other, seemingly useless, information such as phorias, base-in and base-out prism measurements and distance and near parameters? When we ask fourth years to obtain this “extra” data, many students, who should never play poker, do not even try to hide their distaste for what they think is a complete waste of time.

There seems to be a dynamic tension and an intense rivalry between those whose approaches to prescribing differ. One side believes writing prescriptions is easy and wants to get that part over with so they can move on to using the “cool” technology. The other side believes that by stripping down tests conducted to help write prescriptions, we are giving up the core of what it means to be an OD. Then, there are those of us who believe in a middle ground, where we can embrace new technology and the expanding scope of practice of the profession to fully understand how the way we prescribe shapes a person’s future.

Patient Deloise gave me, Dr. Harris, the opportunity to take advantage of this middle ground.

Meet Deloise

In May of 1984, Deloise was 12 years old. She was referred to me by another OD. He had chosen not to give her glasses and wanted me to determine her prescription. At Deloise’s last visual evaluation 18 months earlier, no need for glasses was identified. Her chief complaints were blurring at distance and, despite sitting in the front row of her classes, having to squint to see the board.

When asked what she liked best about school, she said riding class. She did not care for math, which also happened to be the class in which she received the worst grades. She had the highest marks in tennis and was a good reader and speller. She was spending 45 to 90 minutes a day on the computer.

Deloise’s mother was about -11.50D OU, and her dad was about -9.50D OU. Her parents would do anything for their child to not end up like them.

|

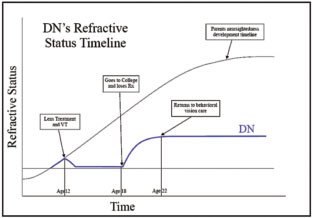

| This refractive timeline shows how glasses and vision therapy helped Deloise (DN) and, alternatively, what happened when she broke her glasses and was lost to follow-up for four years. |

Embrace the Middle Ground

Deloise’s unaided distance visual acuities were 20/200 OD and 20/70 OS. At near, they were 20/20 OU. Her distance subjective measurements—least minus to the first good 20/20—were -1.75 -0.25x130 OD and -1.00 -0.25x180 OS. Maybe there should have been a bit more minus than the acuities suggested, but they were not wildly off.

The base out at distance was x/5/4, and the base in at distance was x/3/-1. Knowing that the base out break should be 19D and the base in break should be 9D for a total range of 28D caused confusion over the range of 8D she showed. Her distance phoria was 3 exo.

At near, the testing broke with tradition. Because she was 20/20 OU at near and had never worn glasses, we removed the refraction noted above and started with nothing in the phoropter. A near phoria of 13 exophoria was found through plano at near, which is where it remained despite the fused cross cylinder showing +0.75. Her base out at near was x/18/12, and her base in at near was x/12/6, neither of which was concerning. Deloise’s positive relative accommodation (PRA) and negative relative accommodation (NRA) were quite revealing. The NRA was +2.25 gross lens in the phoropter, and, as the lenses transitioned to the minus direction, Deloise was unable to clear the chart at +0.25. This raised my hopes that she could be helped if all the minus on the subjective was not yet embedded.

Stress-point retinoscopy, which was in its infancy at the time and not as trusted as it is now, showed that Deloise could handle +0.50 at near. Her parents wanted her to undergo vision therapy, and I agreed that this was the best option. Due to her visual acuity measures and the fact that she was squinting, a near vision correction was needed. After consulting with the referring OD, we decided on the following prescription: -0.50/+1.00 add OD and -0.50/+1.00 add OS. This would allow a good 20/40 at distance and eliminate squinting.

Deloise received her glasses and began vision therapy. She was diligent in completing therapy at home and wearing her glasses at all times in school and as she needed them at home. Her unaided visual acuities improved to 20/40 OD, 20/30 OS and 20/25 OU. Her distance subjective measurements, which were a solid 20/20 OU, were now -0.50 OD and -0.25 x 180 Plano OS.

The base out at distance improved to 8 / 14 / 8 and the base in to x / 8 / 4. The distance phoria was 2 exophoria. At near, PRA and NRA, which improved to +2.50, -2.75, saw the biggest changes. Stress-point retinoscopy showed that Deloise could now handle +1.00 at near. Since her unaided visual acuities were now better than 20/40, her glasses were changed to plano at distance with a +0.75 add OU. Deloise completed about 20 total vision therapy sessions.

Mistakes and Consequences

So, what happened to Deloise? Fortunately, she was not lost to follow-up. She remained the same from the conclusion of vision therapy until high school graduation and did not become more myopic over those years. That is the good news. But, she ended up going to college more than 2,500 miles away and was not seen for a few years. She broke her glasses within the first few weeks of school and never had them replaced. She returned four years later with her tail between her legs and glasses that were clearly minus lenses—they were -3.00D OU.

Using plus for near, under-prescribing at distance and providing vision therapy helped change the course of Deloise’s myopia progression, allowing her to remain stable for many years—with the help of glasses for near—and see well at distance (20/20- OU unaided). Without her plus lenses during those four years of college, however, she found herself right back on the myopia progression train. Deloise finally stopped progressing at about -3.00 OU.

If you remember, Deloise liked riding. She became too big to be a jockey but had an incredible sense of time and space and became an in-demand exercise rider for top-level racehorses. She rode horses and made recommendations to the groups who wanted to invest in them. Her opinions about those horses were and are valued greatly. Oh, and Deloise got married. Her husband’s refractive status? You guessed it: -9.00D OU!

Deloise’s was not an exceptional or extraordinary case but an example of how the way we prescribe today has an impact on the future. By prescribing judiciously from our findings, and adding in vision therapy when necessary, we can prove to patients that they are not doomed by their genes. But, we must first take the time to listen to our patients’ needs, conduct those extra tests and analyze our data to determine the appropriate treatment plan.