Binocular vision problems should not frighten optometrists—many of these conditions are relatively easy to diagnose and manage. We know more about treating these conditions today than we did 20 years ago thanks, in part, to an increase in binocular vision research.

In particular, the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group’s (PEDIG) Amblyopia Treatment Study (ATS) and Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) have helped optometrists develop a diversity of treatment options for patients with binocular vision conditions.

These patients are likely to present to your office as children whose parents bring them to an eye exam. They’ll explain that “His teacher thinks he needs an eye exam because he has problems reading,” or, “She failed a screening. They said she has a lazy eye.” They may also present as adults who complain that a new job sits them in front of their computers all day. They’re likely to tell you, “By the end of the day, I can’t read, I have a splitting headache and I’m seeing double.”

All of these patients can be evaluated and managed in your optometric practice, and as optometrists we have the unique ability to change patient’s lives by treating these visual conditions.

|

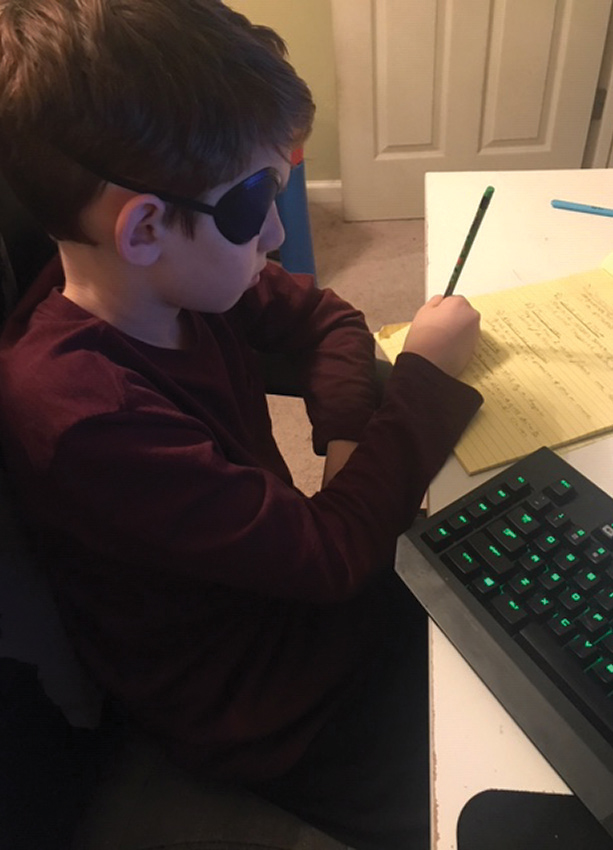

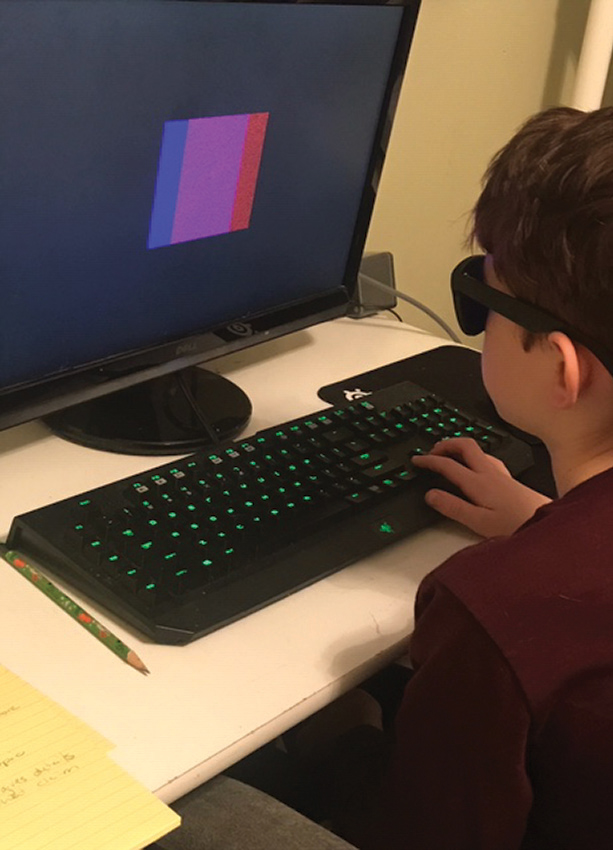

| Here, a young patient is seen patched and performing monocular oculomotor activity using the Home Therapy System (Vision Therapy System). Click image to enlarge. |

More Than Reading Problems

Reading in school-aged children between kindergarten and third grade usually involves learning how to read; learning the names and sounds of the letters and then putting them together to make simple words and sentences. Once the child has mastered how to read, they begin to read to learn. This process begins in fourth grade and continues through adulthood. As classes become more advanced, books feature fewer images, the font size gets smaller and words get longer. Reading assignments take longer to complete and are more demanding on the visual system.

Treating a patient with these reading problems starts with a detailed history. The phrase “reading problems” itself can mean different things to different people. By asking more specific questions, you can better streamline your exam and testing.

Reading problems can be broken into two main classifications: visual efficiency problems and visual processing or perceptual problems. Each of these groups experiences different symptoms. Visual efficiency problems manifest as signs of discomfort when reading, such as double vision, headaches, words moving on the page, words blurring and loss of place when reading. These can indicate a problem with refractive error, binocularity, accommodation or oculomotor skills. These symptoms are more common for patients in that “reading to learn” phase, when reading becomes more demanding.

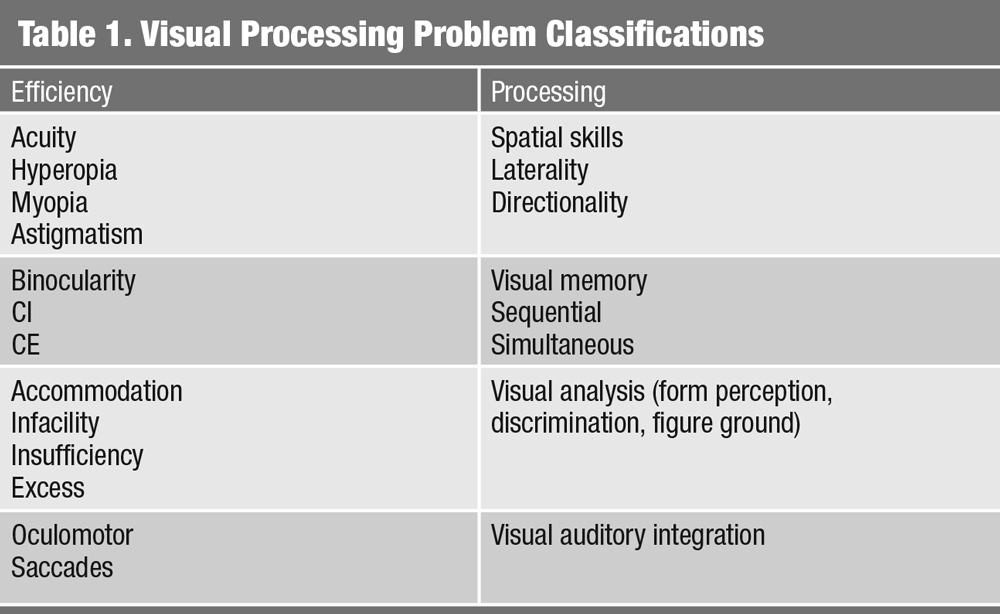

In contrast, visual processing problems manifest as more cognitive/academic type symptoms. These include poor comprehension, letter and word or number reversals, difficulty remembering what was read, struggling to recognize words and problems sounding out words. Visual processing problems come into play more in that earlier phase—when a child is learning how to read. These problems can be classified according to the visual skill affected: spatial skills, memory, analysis and visual auditory integration (Table 1).

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

Evaluation

The history should include questions on recent changes to health if the symptoms are acute. Patients on certain medications—particularly for attention problems and depression—may have accommodative problems, patients who have had a traumatic brain injury (TBI) or concussion may also have binocular problems (See ‘Five Additional Causes for Binocular and Accommodative Problems’).

As with any patient, the most important thing is to first determine an adequate refractive prescription. Because pediatric patients can accommodate large amounts during retinoscopy, a cycloplegic refraction should be considered if the child has moderate to high hyperopia, amblyopia, esotropia or if the retinoscopic reflex is unstable.1 Additionally, a cycloplegic refraction is strongly recommended if the patient is not correctable to 20/20. With patients who are myopic, a full cycloplegic refraction is not generally indicated; refraction with tropicamide can be adequate.1

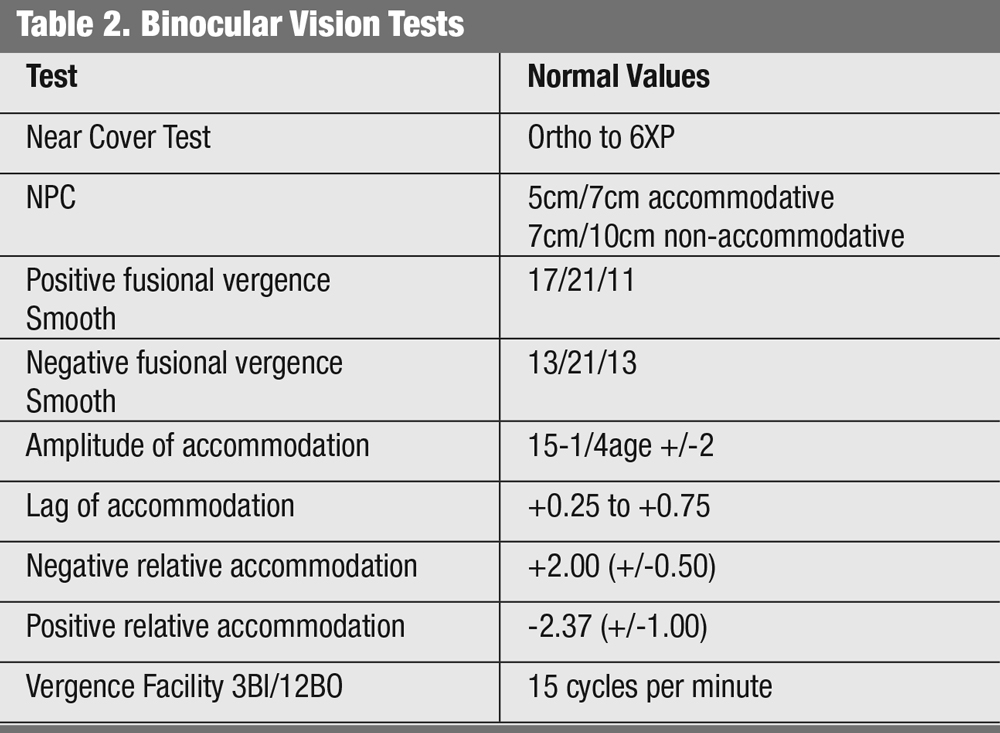

If visual acuity is reduced at distance or near, this reduced acuity may adversely impact the patient’s ability to read. However, even if visual acuity is adequate, and the refractive error is minimal, a patient complaining of asthenopic symptoms when reading requires a thorough binocular and accommodative work-up. Basic techniques such as stereopsis, cover test and near point of convergence can provide significant information regarding a patient’s binocular status. Keep in mind, issues with binocular vision can manifest at distance as well. Additional tests, including vergence ranges, particularly at near, can also be helpful in determining a diagnosis (Table 2).

Finally, in all cases, a thorough health assessment is necessary to rule out pathology. Findings such as a visual field defect, relative afferent pupillary defect, optic nerve edema or atrophy or retinal pathology indicate a non-functional cause for the defect and must be treated appropriately.

Five Additional Causes for Binocular and Accommodative Problems• Concussion – a recent study found that 49% of children and adolescents had CI after a concussion.1 • ADHD – a retrospective review found that 9.8% of children with CI had a diagnosis of ADHD; and 15.9% with a diagnosis of ADHD had a diagnosis of CI.2 • Lyme disease – a retrospective review of pediatric and adult patients with Lyme disesae found that 53% had CI.3 • Stimulant medications (methylphenidate, dexmethylphendate, dextroamphetamine) – package inserts report “Difficulites with accommodation” or “blurring of vision.” • SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, citalopram) – package inserts report risk of blurred vision.

|

Lessons from the Literature

One of the most common conditions that can affect a patient’s near binocular status is convergence insufficiency (CI).2,3 This is generally classified by the triad of exophoria at near, receded near point of convergence and reduced positive fusional vergence ranges (base out) at near.

The CITT was a randomized clinical trial looking at vision therapy as a treatment for CI in children ages nine to 18 years.2 Twelve weeks of office-based vision therapy were compared with office-based placebo therapy as well as home-based pencil push-up therapy and home-based computer therapy plus pencil push-ups. It found that patients in the office-based vision therapy group had lower scores on the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS), a survey used to quantify symptoms in children with CI, as well as near-point of conversion (NPC) and positive fusional vergence (PFV) values that had improved significantly more than the other treatment groups.

Subsequent research found that most of the children who were asymptomatic after the 12 weeks of therapy, maintained those improvements for at least a year after therapy.3 From the many papers that arose from the work of the CITT study, clinicians now have better evidence for the testing/treatment of this condition including a validated symptom survey, criteria for diagnosis and treatment options.2,3

For instance, the CITT study helped identify the signs and symptoms important to determine patient selection as well as gauge if treatment is successful.2,3 We learned that office-based vision therapy is the most successful treatment for CI patients. Many optometrists now incorporate the CISS as a screening tool for school-aged patients.4 The CISS has been validated for children ages nine to 18. Investigators say a score of 16 or greater is the cutoff for distinguishing children with symptomatic CI from those with normal binocular vision.4

|

| Click table to enlarge. |

For adult patients, a score of 21 or greater indicates symptoms of CI.5 Recently, published work by the CITT study group, found that after 16 weeks of office based vision therapy vs. office based placebo therapy, signs of CI such as NPC and PFV improved, but the CISS scores were not statistically significantly different between the two groups.6 The authors cautioned that the CISS may not be the best metric to use alone to determine whether or not treatment is successful in children.6

Although, to date, no large-scale randomized clinical trials of vision therapy for CI in adults are available, smaller scale studies show some success.5-8 One such study on adult males found that 62% of patients who received in-office plus home therapy and 30% of patients who received only home therapy were successfully treated with vision therapy.8 Many of the therapy techniques used in this study were the same used by the CITT group.

The vision therapy protocol in the CITT study focused on accommodation, voluntary convergence and fusional vergence.2 Although many techniques can be accomplished with traditional methods, more sophisticated and equipment intensive therapy techniques such as vectograms, aperture rule and computerized orthoptics were also included in CITT.2

When conducting vision therapy, assess the patient’s signs and symptoms at regular intervals.2 Although the CITT used 12 weeks of 60-minute therapy sessions for the study, in practice, sessions may be closer to 30 or 45 minutes.2

In the same way that research has improved our understanding of CI, the PEDIG ATS studies have helped optometry deepen its understanding of amblyopia treatment.9,10 From these studies, we know that when seeing a patient with amblyopia, the recommended treatment is to prescribe glasses and then monitor the patient’s visual acuity every six to eight weeks.9,10 That research shows that, in patients with isoametropic amblyopia, 73% obtained 20/25 visual acuity (VA) in one year with glasses alone.9

In patients with anisometropic amblyopia, approximately one-third showed resolution of the amblyopia with refractive correction alone and more than 75% of patients improved two lines or more in visual acuity.10

Similarly, in patients with strabismic and combined mechanism amblyopia, 75% improved two or more lines of visual acuity with spectacle correction alone, with resolution of amblyopia occurring in more than a third of patients.11 Treating patients with spectacles first can help improve visual acuity, which can make penalization therapy easier for a patient.

|

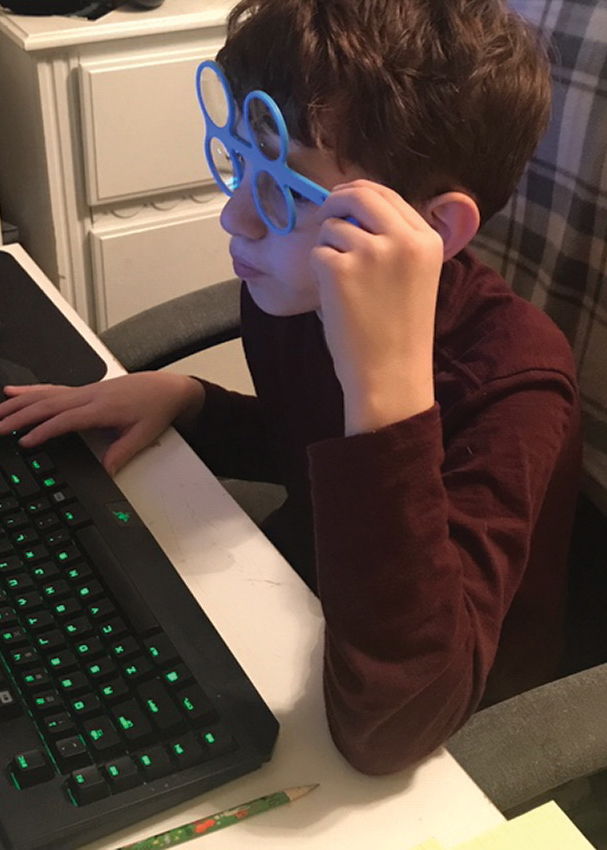

| Here, a patient is seen partaking in a binocular accommodative activity using a computerized therapy system. Research is now showing that these types of treatments can have a lasting impact. Click image to enlarge. |

Patching

If patients do not show acuity improvement with spectacle correction alone, or if visual acuity plateaus for two consecutive visits, additional amblyopia treatment should be initiated.

Currently, penalization therapy is a mainstay of amblyopia treatment. For patients with moderate amblyopia (20/80 acuity or better), two hours of daily patching is recommended, based on data from the ATS.12,13

Research suggested that a weekend atropine regimen was as effective as daily atropine for amblyopia treatment, and that Bangerter filters can be used as an alternative to patching as a treatment for patients with amblyopia.14,15

Patients can purchase a variety of adhesive patches from a pharmacy, but you may also want to order cloth patches meant to fit over glasses and cover not only the eye itself but also above, below and to the side of the glasses.

Prior to the ATS studies, research had no information on potential treatment for children older than seven with amblyopia. The ATS studies found that, among children seven to 12 years old, more than half with amblyopia responded to treatment.16 In an older group, children between 13 and 17 years old, only 25% responded to treatment; however, among patients who had not previously been treated for amblyopia, 47% of patients responded to treatment.16

One of the major criticisms of amblyopia treatment is that treating children and teenagers with patching can be difficult for both patient and parent. Children do not like to wear a patch and may try to remove it, frustrating parents. If the patch is placed on the glasses, the child may refuse to wear the glasses.

The latest ATS studies are evaluating newer binocular treatments for amblyopia. These treatments often use games or tasks that employ dichoptic stimuli, which use red/green glasses to form a binocular percept, showing different images to each eye. The image presented to the sound eye has reduced contrast, which allows patients that are normally unable to fuse images the ability to use their eyes together. As the patient plays the game successfully, the contrast increases until they are able to fuse the images with 100% contrast in each eye.

PEDIG first evaluated a binocular treatment using the Hess Falling Blocks, a game similar to Tetris. In a study of five to seven year olds using this treatment for 16 weeks, researchers found that the amblyopic eye acuity improved with patching and video game play; however, the improvement was not as good in the video game group as in the patching group.17 Surprisingly, compliance was actually better in the patching group.17 In an older cohort aged 13 to 16 years, amblyopic patients had a minimal response to the therapy.17,18

Other technologies have employed the use of dichoptic movies instead of video games for amblyopia. One study found that eight children, ages four to 10, with amblyopia who viewed 3D movies for two weeks showed an improvement in visual acuity of two lines.20

Bringing It To Your Clinic

When a practitioner encounters a patient with reading problems, or symptoms of double vision or headaches when reading, doing an NPC, near phoria and near PFV ranges can provide a lot of information and help with the diagnosis of CI. The patient’s findings can be compared with the norms from the literature.

The treatment of a CI can employ brock string for convergence work, monocular accommodative facility or near far hart chart for accommodation, and distance hart chart for saccades. The therapy can advance to vectograms, aperture rule and lifesaver cards for convergence. The practitioner should reevaluate the patient after eight or 10 sessions. If the patient is not showing any improvement in signs or symptoms, another etiology for the condition might need to be explored.

If the patient does not tolerate a patch, atropine is another option, starting with 1% atropine on weekends. If prescribing atropine, be sure to educate the patients on pupillary dilation and blur. Atropine with a full distance prescription causes penalization at near only, so if it is during the school year make sure that your patient is able to easily read age-appropriate font with the amblyopic eye. If near print is blurry, you may have to consider a bifocal for schoolwork. Although the incidence of side effects with 1% atropine in the ATS trials was very low, doctors must educate patients and parents on all potential side effects. These can include facial flushing, increased heart rate and dry mouth.

Keep in mind, that although atropine is an effective treatment for amblyopia, it might not be the best option for a patient with light eyes, as these children will develop one dilated large black pupil and one noticeably light eye. If cosmesis is a concern, other treatment options—such as patching—may be appropriate for these patients. Additionally, if your patient will be spending time outdoors, make sure that they are wearing sunglasses or photochromatic lenses to decrease sensitivity to bright sunlight.

For patching, atropine or Bangerter filters, patients should be monitored every eight weeks for VA improvement. If the VA is improving, the penalization method can continue until vision is stable. If improvement is minimal or if acuity plateaus, increasing the hours of patching from two to six, or changing the treatment method is acceptable.21 Patients should be monitored for a year after treatment is discontinued, as research shows a quarter of patients may show a regression in VA.22

|

| This patient is performing a vergence activity with computerized vision therapy system. Click image to enlarge. |

Binocular Options

If you would like to incorporate bi-ocular or binocular therapy into your practice, you can use basic red/green targets for your patient. Commercially available matching games, playing cards and other activities that patients with amblyopia can use to incorporate binocular therapy into their treatment plan. Practitioners can also make worksheets using red and green text that the patient reads with red-green glasses and a filter but pay attention to the cancellation. Monocular fixation in a binocular field (MFBF) therapy is another method that can be used treat amblyopia. The patient wears a red filter over the sound eye with no filter over the amblyopic eye and completes activities using a red pen or pencil that can be seen by the amblyopic eye only.

These bi-ocular and binocular therapy techniques are most appropriate for patients with refractive amblyopia or patients with particularly small angles of strabismus. Patients with large angles of strabismus are generally not best managed with binocular techniques unless there is a mechanism to correct for their angle of strabismus.

If you want to try binocular therapy instead of penalization, or if the visual acuity plateaus, numerous options are available. Many companies have their own binocular therapies, although none have been studied in a large randomized clinical trial. One such company, Vivid Vision, employs the use of virtual reality goggles with their platform to treat amblyopia, strabismus and vergence disorders. Their protocol involves having the patient wear virtual reality goggles and play interactive games that have the patient stop oncoming targets with their hands, pop targets with their fingers or aim their eyes to look at a target.

A Few Helpful Pointers

Children with binocular problems can present with symptoms that span across a spectrum that ranges from asymptomatic/avoider, to avoider to symptomatic. A child with reading trouble who persists in trying to read and but gets headaches is symptomatic. When children are too uncomfortable to even try reading, they are avoiders. Children who adapt by covering an eye when reading, or holding things farther away, can be considered asymptomatic/avoiders.

Similarly, when examining a child with amblyopia, particularly if it is anisometropic and the parent had no concerns prior to the child’s failing a school screening, it is important to realize that child may not complain that one eye does not see. A child with amblyopia does not realize they could be seeing things differently.

Children with learning disabilities may have refractive errors or problems with binocular/accommodative skills. A study, looking at 50 children on Individual Education Plans (IEPs) compared with age-matched controls and did full binocular work ups. The children with the IEPs had various types of learning disabilities, many of which were specific to reading. The study found that “there are significant associations between reading speed, refractive error and vergence facility.”

The authors did not claim that the sole cause of the children’s reading difficulties was visual or binocular, as these problems can be multifactorial. However, they did recommend that students being considered for an IEP should have a full eye examination, including binocular vision testing.23 Vision is a piece of the pie when dealing with reading problems.

The next time you encounter a patient whose history is suggestive of a binocular problem—including amblyopia—approach the exam in a sequential pattern using history to guide your testing. Incorporate basic binocular testing into your evaluation and remember to first rule out any potential pathology.

Regarding your treatment of these patients, at the very least, educate your patients about these conditions and make some pertinent and educated recommendations. Refer the patient to a vision therapy provider for treatment or do it yourself if this is a treatment modality you are comfortable providing.

Dr. Bodack is an associate professor and chief of the Pediatric Primary Care Service at Southern College of Optometry.

Dr. Jenewein is an assistant professor at Salus University and its principal site investigator for the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group.

| 1. Manny R, Hussein M, Scheiman M, et al, Tropicamide (1%): an effective cycloplegic agent for myopic children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(8):1728-35. 2. Scheiman M, Cotter S, Kulp M, Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group, et al. Randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(10):1336-49. 3. Scheiman M, Cotter S, Kulp M, Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group, et al. Long-term effectiveness of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Optom Vis Sci, 2009;86(9):1096-103. 4. Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell G, et al. Validity of the convergence insufficiency symptom survey: a confirmatory study. Optom Vis Sci. 2009:86(4);357-63. 5. Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell G, et al. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24(5):384-90. 6. CITT-ART Investigator Group. Effect of vergence/accommodative therapy on reading in children with convergence insufficiency: a randomized clinical trial. Optom Vis Sci. 2019;96(11):836-49. 7. Scheiman M, , Gallaway M, Frantz K, et al. Nearpoint of convergence: test procedure, target selection, and normative data. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80(3):214-25. 8. Birnbaum M, Soden R, Cohen A. Efficacy of vision therapy for convergence insufficiency in an adult male population. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70(4):225-32. 9. Wallace D, Chandler D, Beck R, et al. Treatment of bilateral refractive amblyopia in children three to less than 10 years of age. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(4):487-96. 10. Cotter S, Edwards AR, Wallace D, Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, et al. Treatment of anisometropic amblyopia in children with refractive correction. Ophthalmol. 2006;113(6):895-903. 11. Cotter S, Foster N, Holmes J, Writing Committee for the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, et al. Optical treatment of strabismic and combined strabismic-anisometropic amblyopia. Ophthalmol. 2012;119(1):150-8. 12. Repka M, Beck R, Holmes J, et al. A randomized trial of patching regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(5):603-11. 13. Holmes J, Kraker RT, Beck R, Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, et al. A randomized trial of prescribed patching regimens for treatment of severe amblyopia in children. Ophthalmol. 2003;110(11):2075-87. 14. Repka M, Cotter S, Beck R, et al. A randomized trial of atropine regimens for treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Ophthalmol. 2004;111(11):2076-85. 15. Rutstein R, Quinn G, Lazar E, et al. A randomized trial comparing Bangerter filters and patching for the treatment of moderate amblyopia in children. Ophthalmol. 2010;117(5):998-1004. 16. Scheiman M, Hertle R, Beck R, et al. Randomized trial of treatment of amblyopia in children aged 7 to 17 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(4):437-47. 17. Holmes J, Manh V, Lazar E, et al. Effect of a binocular iPad game vs part-time patching in children aged 5 to 12 years with amblyopia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(12): 1391-400. 18. Manh V, Holmes J, Lazar E, et al. A randomized trial of a binocular iPad game vs. part-time patching in children aged 13 to 16 years with amblyopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;186:104-15. 19. Holmes J, Manny R, Lazar E, et al. A randomized trial of binocular dig rush game treatment for amblyopia in children aged 7 to 12 years. Ophthalmol. 2019;126(3):456-66. 20. Li S, Reynaud A, Hess R, et al. Dichoptic movie viewing treats childhood amblyopia. J AAPOS. 2015;19(5):401-5. 21. Wallace D, Lazar E, Holmes J, et al. A randomized trial of increasing patching for amblyopia. Ophthalmol. 2013;120(11):2270-7. 22. Holmes J, Beck R, Kraker R, et al. Risk of amblyopia recurrence after cessation of treatment. J AAPOS. 2004;8(5):420-8. 23. Quaid P, Simpson T. Association between reading speed, cycloplegic refractive error and oculomotor function in reading disabled children vs. controls. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(1):169-87. |