|

A 72-year-old Caucasian female presented with a longstanding history of blurred vision in both eyes all her life. In fact, she reported growing up having high myopia until she had cataract surgery in both eyes approximately 10 years earlier. Her vision improved following cataract surgery but it was still never perfect. She reported a slow progressive loss of vision in her right eye over the past three or four years. The left eye sees better but, she reported, it’s not as sharp as it used to be.

Her medical history is significant for Type II diabetes for more than 10 years. Her blood sugar is controlled and her last hemoglobin A1c was 6.0. She had a head injury relating to a motor vehicle accident approximately 12 years ago, which resulted in a cerebral hemorrhage. She now gets occasional seizures. This has been stable.

|

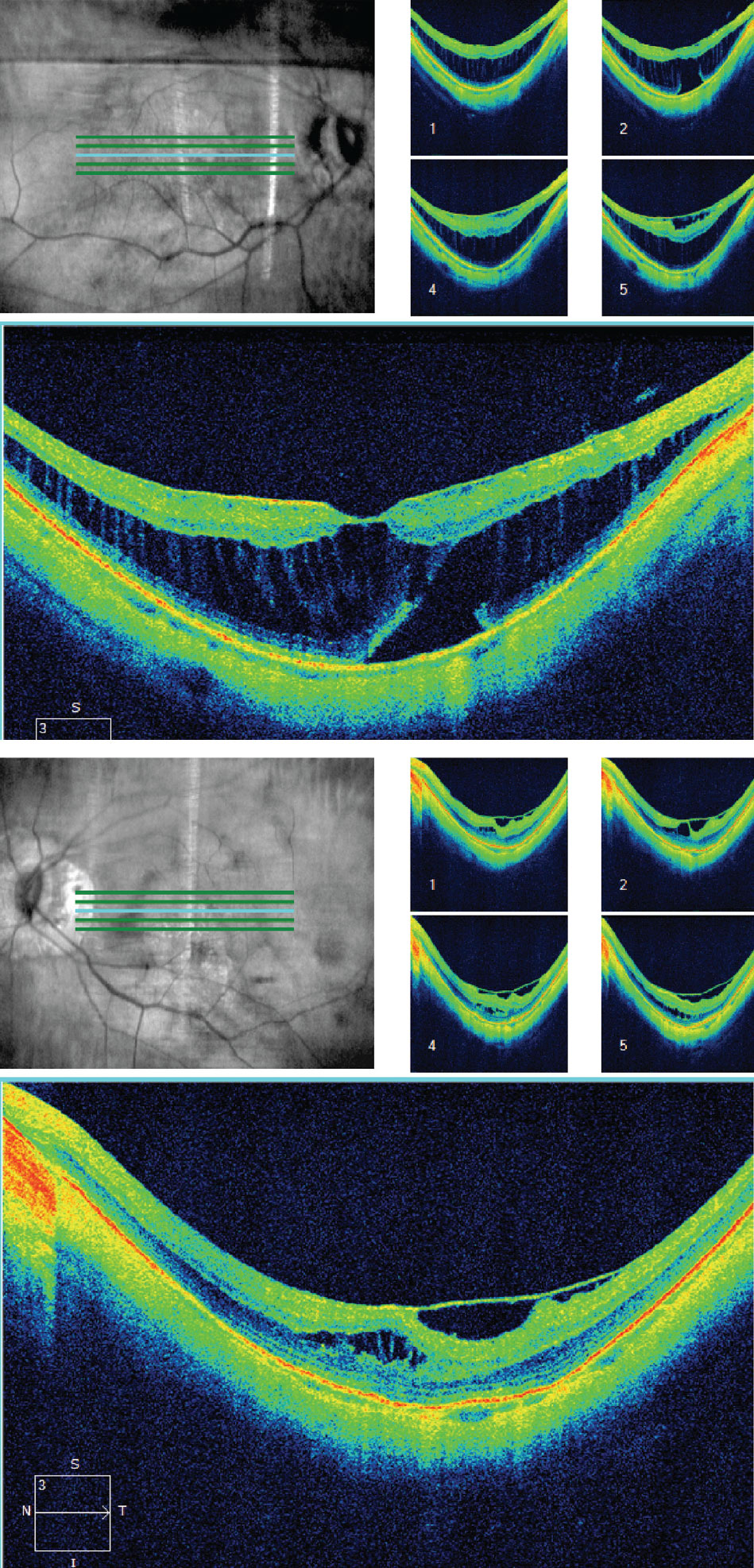

| Fig. 1. These OCT images of the right (at top) and left eye on initial presentation. Note the obvious changes in both maculae. Click image to enlarge. |

Evaluation

On examination, her best-corrected visual acuities were 20/80 OD and 20/40 OS. Her confrontation visual fields were full-to-careful finger counting OU. Her ocular motility testing was normal, and the pupils were equally round and reactive to light without an afferent pupillary defect. The anterior segment was significant for the presence of clear posterior chamber intraocular lenses in both eyes. Her tensions by Tonopen (Reichert) measured 14mm Hg OU.

On dilated fundus exam, the vitreous was clear. The optic nerves were tilted with a small cup, and there was peripapillary atrophy present around both optic nerves. Obvious retinal changes were visible in the macula of each eye. An SD-OCT was performed and is available for review (Figure 1).

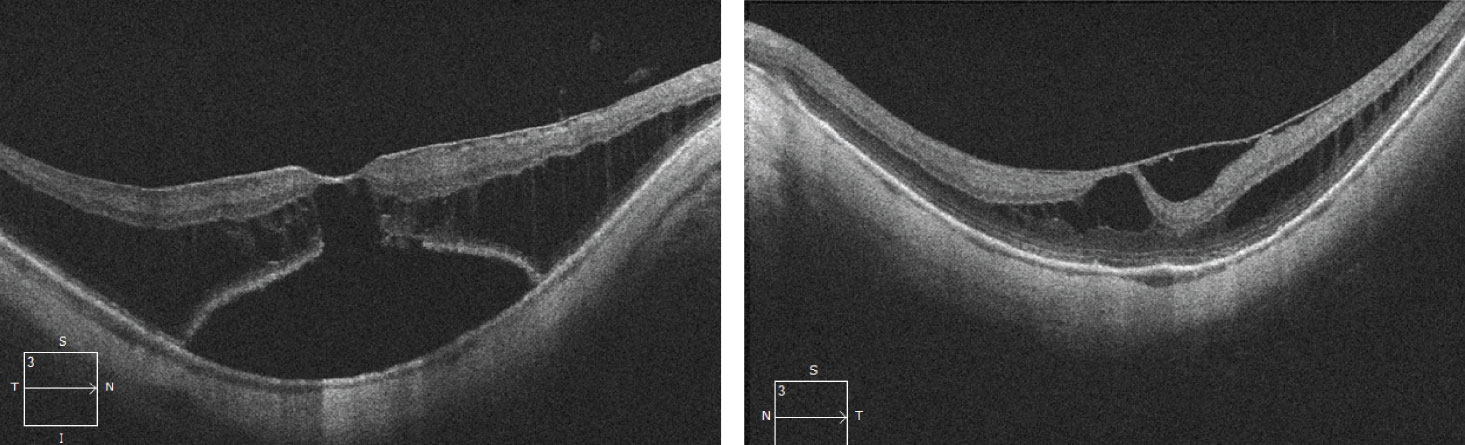

We continued to follow this patient closely. On exam one year later, her vision eye had declined to 20/400 OD and 20/80 OS. The SD-OCTs are available for review (Figure 2).

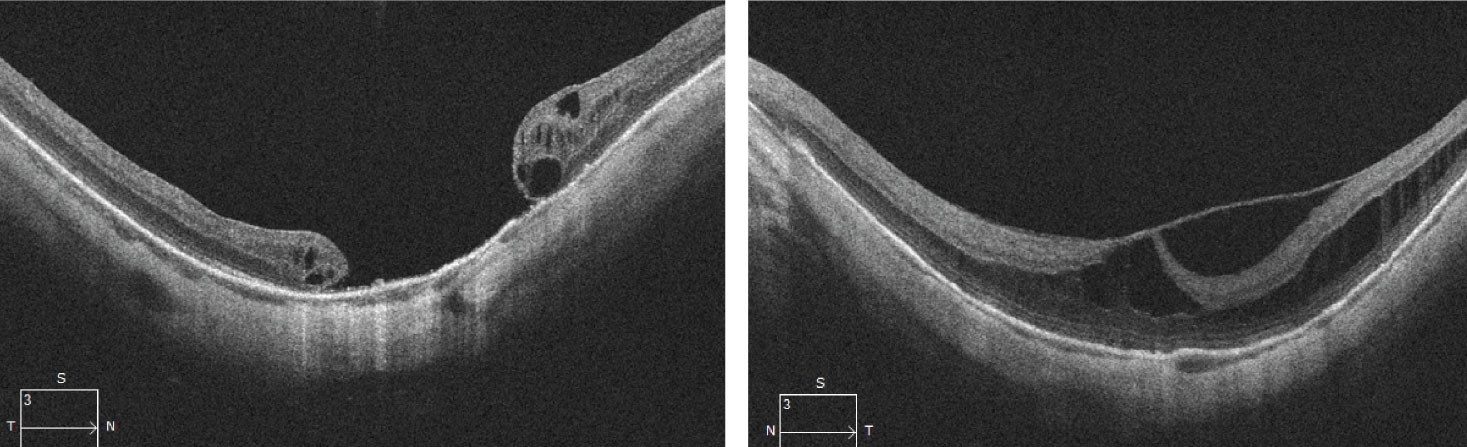

Over the next two years, the vision in her right eye never stabilized or improved and now her left eye is starting to decline. The OCT from two years later is also available (Figure 3).

|

| Fig. 2. This set of OCT images were taken one year later. Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. On her initial visit, what is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Cystoid macular edema.

b. X-linked juvenile retinal schisis.

c. Myopic tractional maculopathy.

d. Central serous retinopathy.

2. On the second visit, the right eye is worse. How would you characterize the right eye based on the OCT?

a. Neurosensory retinal detachment and loss ellipsoid zone.

b. Retinal pigment epithelium detachment.

c. Impending macular hole.

d. Full-thickness macular hole.

3. On the third visit, how would you characterize the right eye at the follow up?

a. Full-thickness macular hole.

b. Pseudo-macular hole.

c. Chorioretinal scaring.

d. Choroidal neovascularization.

4. On the third visit, how should the left eye be managed?

a. Observation.

b. Anti-VEGF injection.

c. Pars plana vitrectomy, membrane peel.

d. Intravitreal injection of Ocriplasmin.

|

| Fig. 3. These OCT images were taken two years later. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Even though our patient is pseudophakic, it is clear from her history and clinical presentation that she was highly myopic as a child and has myopic degenerative changes in her posterior pole. It’s not surprising the OCTs provide the greatest insight into what’s happening with her vision. In both eyes, right worse than left, they clearly show schisis-like cavities within the sensory retina and obvious retinal thickening. On the OCT in the right eye, you can also see a pocket of subretinal fluid posterior to the schisis as well as an obvious epiretinal membrane in the left eye resulting in persistent traction on the macula. This clinical picture is consistent with a diagnosis of myopic traction maculopathy (MTM).

|

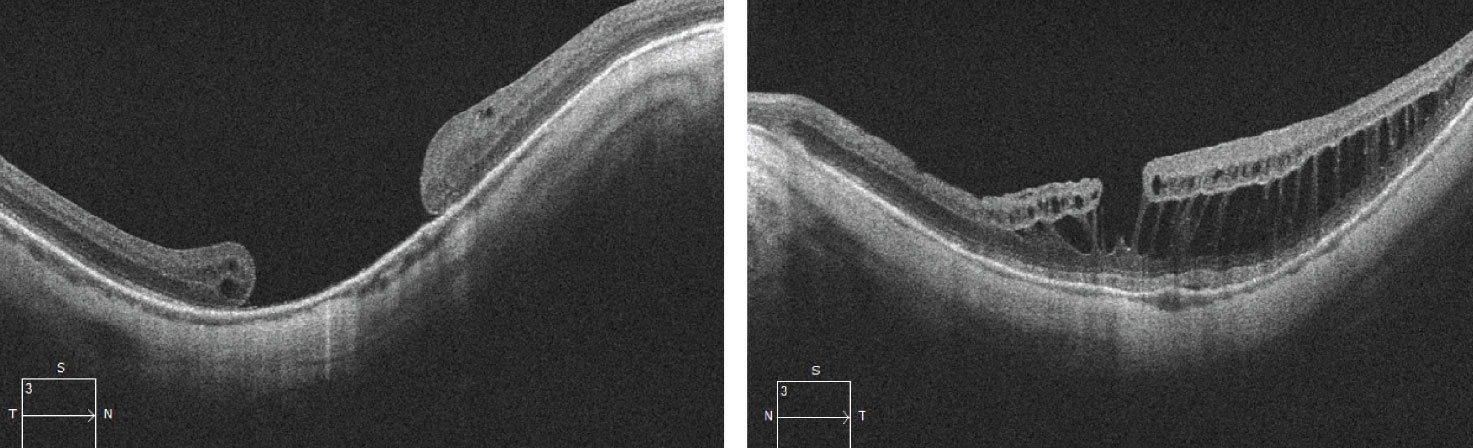

| Fig. 4. These images were gathered four years later. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

This condition develops from a complex interaction of tractional forces on the macula in highly myopic eyes due to an adherent vitreous cortex in the presence of myopic degenerative changes, such as posterior staphyloma.1 The hallmark of this condition is the presence of a schisis-like thickening in the outer retina. In addition, patients may also have epiretinal membrane, lamellar or full-thickness macular hole (FTMH) and foveal retinal detachment (FRD).1-2 It is thought to be present in 9% to 34% of highly myopic eyes.2

Beyond the features that are easily visualized on clinical exam with myopic degeneration, such as peripapillary atrophy, lacquer cracks, posterior staphyloma and even epiretinal membrane, the schisis-like cavities are essentially invisible when looking with indirect ophthalmoscopy at the slit lamp with a 90D or 78D lens. It wasn’t until 1999 when OCT emerged that we fully recognized the clinical spectrum of this condition.3

The natural course of MTM is unclear, especially when paired with a FRD. Some investigators believe that most patients will progress to a FTMH when FRT is present.2 In eyes that have had vitrectomy after the development of a FTMH, visual outcomes are worse than if a vitrectomy was done before the development of a FTMH.2 That was the concern with our patient where it was clear on the second OCT that she had progressed to an impending FTMH with significant FRD. Our patient did have a vitrectomy and membrane peel within a week of that visit, and it appeared to be successful, but two weeks after the surgery, she developed a FTMH anyway, which was followed a month later by total retinal detachment. She had a second surgery, which was successful in re-attaching the retina, but the macular hole remained and has since been stable. This is evident on the third OCT where the FTMH can be seen. The OCT shows a complete loss of the sensory retina and photoreceptors in the macula.

Unfortunately, as luck would have it, the left progressed over a two-year period. She noted that her vision in the left eye had declined, and indeed the acuity dropped from 20/30 to 20/80 with an increase in the foveal macular traction. She underwent a vitrectomy and membrane peel in her left eye, which has been successful despite the persistent schisis cavities present on OCT exam. Her acuity returned to 20/30 where it has been stable now for almost two years. The OCT is remarkable in that vitreomacular adhesion and traction that was present before appears to be absent but unfortunately, the schisis is still present and now she has a lamellar hole. The hope is that without persistent macular traction, this will remain stable. She continues to be followed closely. n

1. Johnson MW. Myopic tractional maculopathy, Pathogenic mechanism and surgical treatment. Retina. 2012;32(Suppl 2):S205-10. 2. Kataoka K, Terasaki H. When and how to treat myopic tractional maculopathy. Retina Today. 2017;12(5):28-30 3. Takano M. Kishi S. Foveal retinoschisis and retinal detachment in severely myopic eyes with posterior staphyloma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128(4):472-6. |

Retina Quiz Answers:

1) b; 2) c; 3) a; 4) c