For years, plaintiffs attorneys have hammered away at the doctrine of off-label application, claiming that doctors should face at least some level of increased liability if they administer a drug in ways unapproved by the FDA. Time and again these arguments have been rejected. The government, courts and regulatory agencies have steadfastly supported a doctors right to practice medicine as he or she chooses given the clear benefits to medical advancement.

Indeed, many drugs and devices approved for one condition are found even more effective at treating another. For example, Topamax (topiramate, Ortho-McNeil) is FDA approved for treating epilepsy and migraines, but psychiatrists have used the drug off-label to treat bipolar disorder. To increase liability would stifle future breakthroughs, the argument goes. Recently, this support manifested itself in the new Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit, which expressly covers some off-label medications.

Still, doctors often approach off-label use with caution, especially in the early stages of the new application of the drug. Regardless of legal liability, no practitioner wishes to place patients at risk for serious adverse events that may have gone undetected due to the absence of preclinical studies. And, it is always possible that society as a whole will change its stance on the importance of protecting off-label usage. Thus do those in the medical field speak of the liability of off-label prescribing, even though it is a well-entrenched medicolegal principle.1

Anxiety regarding this principle lies at the heart of a controversy occurring in the retina world: the off-label use of Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech) to treat neovascularization secondary to wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other retina conditions. Originally approved for the treatment of colorectal cancer, Avastin was found last year to be effective at treating a small cohort of AMD patients.2 News spread quickly, and by this spring, several thousand AMD patients had received the off-label therapy.

|

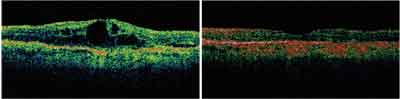

| This patient had occult CNV with no classic lesion (3.60 disc areas) and visual acuity of 20/160 (42 ETDRS letters) at baseline. Twelve months after treatment with 0.5mg ranibizumab, visual acuity improved to 20/80 (56 ETDRS letters). |

Avastin was in danger of stealing Lucentis thunder. Based on the burgeoning popularity of the off-label drug, which is far less expensive than Lucentis, Wall Street analysts downgraded Lucentis sales potential from $1.1 billion to $600 million, and Genentechs stock took a 4% dip.

|

| Optical coherence tomography images show the same patient at baseline and 12 months after treatment with Lucentis. |

Now, with Lucentis approved by the FDA, the two Genentech drugs are poised to compete against each other. Here are the factors that could determine the winner.

A New Standard

No matter which drug prevails, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs, such as Avastin and Lucentis, represent an exciting new age in retina treatment. For the first time, doctors can offer a significant number of AMD patients the chance of improving visual acuity rather than merely stopping or slowing progression of the disease. While current mainstay treatments, namely thermal laser photocoagulation and photodynamic therapy, seek to destroy new vascular growth, anti-VEGF therapies help stem the process of neovascularization itself by blocking the angiogenic factors that cause it.

Avastin is a humanized mouse monoclonal antibody directed against VEGF. It received FDA approval for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in February 2004, the first anti-VEGF drug approved by the agency.

Avastin came to the attention of Philip Rosenfeld, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, during his involvement in early clinical studies of Lucentis, which like Avastin, is a VEGF inhibitor. Positive clinical responses convinced him to look at other anti-angiogenic medications.

Dr. Rosenfeld and the institute undertook the Systemic Bevacizumab (Avastin) Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (SANA) study.2 Researchers administered two or three doses of bevacizumab (5mg/ kg) at two-week intervals to 18 eligible patients. Follow-up evaluations revealed rapid improvements in visual acuity, angiographic and optical coherence tomography (OCT) outcomes.

At one week, median and mean visual acuity letter scores had increased by eight letters in treated eyes. By two weeks, they had improved by 12 letters. The median and mean central retinal thickness measurements also decreased significantly. Angiography revealed a reduction or absence of leakage from the lesions. Overall, no patient lost a letter of vision, and more than 40% gained three or more lines, the study found. Some patients gained six or more lines.

Although patients encountered no serious adverse events, systemic Avastin administered to cancer patients poses a risk of thromboembolic events.3 So, researchers sought to reduce the drugs dosage. Literature published in the 1990s debunked Avastins ability to penetrate the retina via intravitreal injection. Finding the conclusions of various studies to be questionable, Dr. Rosenfeld reduced the dose of the drug by about 400 times and began injecting it into patients eyes, with positive results.4

Currently, the drug is most often administered via intravitreal injection. Anecdotal reports indicate physicians use Avastin to treat diabetic macular edema, branch retinal vein occlusion, central retinal vein occlusion, cystoid macular edema and even more rare conditions such as Coats disease. While sometimes employed as a first-line therapy, Avastin is usually used after other treatments fail.

Experimentation with Avastin drew inspiration in part from what some consider a limited treatment effect of Macugen (pegaptanib, Eyetech Pharmaceuticals/Pfizer).5 Macugen, which was approved in December 2004, is also an anti-VEGF molecule.

Macugen has been shown to be an effective therapy for neovascular AMD.6 In two prospective, randomized, studies that involved 1186 patients, efficacy was demonstrated for three doses (0.3mg, 1.0mg and 3.0mg). Seventy percent of patients who took 0.3mg lost less than 15 letters of acuity vs. 55% of patients in the placebo group.6 Further, the researchers found that 33% of patients who received macugen maintained their visual acuity or gained acuity vs. 23% in the placebo group.6 And, as early as six weeks after beginning therapy with the study drug, and at all subsequent points, the mean visual acuity among patients receiving 0.3 mg of pegaptanib was better than in those in the placebo group.6

One difference between Macugen and Avastin, however: Macugen targets only a single splice length of the growth factor, known as VEGF 165.5 After one year of treatment with Macugen, only 6% of patients demonstrated improvement of visual acuitya significant enhancement over the 2% whose vision improved without therapy but still modest.6 Also, in certain classes of AMD patients, Macugen has not been reported to reduce the rates of moderate visual loss.5-7 Nevertheless, some retinal experts expect Macugen to play a role in adjunctive or prophylactic therapy.

Approved this summer, Lucentis is an antibody binding site (Fab) fragment. Lucentis and Avastin both bind to and inhibit all forms of VEGF-A. In June, Genentech released phase III clinical data showing that patients who had wet AMD experienced a 16-letter benefit vs. the control group after one year of therapy. Patients received 0.3mg or 0.5mg injection doses once a month for the first three months, and then once every three months. At three months, treated patients gained 2.9 letters of vision (0.3mg group) and 4.3 letters (0.5mg group), while control subjects lost 8.7 letters.

|

| Lucentis is an antibody binding site (Fab) fragment that binds to and inhibits all forms of VEGF-A. |

First To Market

When word of Avastins success circulated, it was quickly embraced by retina subspecialists, who were reluctant to wait for FDA approval of Lucentis when fewer than 10% of their wet AMD patients could expect improved vision. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO), as of this spring, some 6,800 Avastin injections had been administered to 5,055 patients at 68 medical centers in 12 countries.

A survey conducted by the American Society of Retinal Specialists found that 92% of respondents believed intravitreal Avastin was somewhat better or much better than other approved or covered therapies. Furthermore, 96% said they thought the off-label application was the same or better in terms of overall safety compared with other FDA-approved or covered therapies.

In April, the American Academy of Ophthalmology sent a letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) calling for Medicare to provide reimbursement for Avastin treatments. At that time, all 17 Medicare carriers covering all 50 states had issued verbal denials of coverage, and seven carriers had issued written denials, according Michael Lachman, publisher of the business publication EyeQ Report.8 In May, however, Pinnacle Business Solutions Inc., a Medicare carrier that operates in several southern states, announced that it would cover off-label use of Avastin when other AMD treatment options have proven ineffective.

While ultimately a clinical decision, the choice between these drugs will likely involve economic factors to some extent. The cost of an injection of Avastin is about $40 to $75, while the cost of a Macugen injection is $1,000, and Lucentis is expected to cost as much or more.

There are some people who were using Avastin as a stop-gap measure until Lucentis got approved, says Jeffry D. Gerson, O.D., of Overland Park, Kan. But, many people will continue to use Avastin because of the money factor. Its less costly to the health-care system and potentially to the patient.

The other side of that argument posits that because insurance carriers will likely cover Lucentis, it will have the edge. Says Mark Dunbar, O.D., also of Bascom Palmer, I think there will be a place for Avastin, but it will probably be among the non-insured or indigent population, or maybe people from other countries who come to the U.S. to get their care.

According to Genentechs own analysis, 81% of patients have enough insurance (Medicare and a supplemental policy or private insurance with a fixed copay) to bring the cost of Lucentis to $50 or less per treatment, says Genentech spokeswoman Dawn Kalmar.

Further analysis, she says, shows that:

Some 3% of patients who have Medicare with a supplemental policy and 5% coinsurance have a copay of approximately $108 per treatment.

Some 1% of patients have commercial insurance and a copay of approximately $215 per treatment.

Some 3% are totally uninsured but are candidates for the companys Access to Care free drug program. Last year, Genentech provided $200 million in free drugs to 18,000 patients, Ms. Kalmar says.

Clinical Concerns

Several retina subspecialists publicly stated their intention to switch to Lucentis when it gained FDA approval. Others have said they will stick with Avastin until data convinces them to switch.

There are several unknowns regarding both drugs. Researchers are not even clear yet whether some characteristics will end up being positives or negatives. For its part, Genentech has engaged in the unusual endeavor of mounting a public relations campaign against its own product (although Ms. Kalmar says that Genentech will not block off-label use of Avastin).

At symposia and in the press, the company has argued that:

The lack of preclinical trials poses the risk that Avastin may end up being toxic in an ocular environment.

Because it contains no preservatives, Avastin may be difficult to keep sterile.

Avastin has a much longer half-life than Lucentis (20 days vs. about four hours). Researchers speculate the larger molecule in Avastin could induce inflammation or adverse immune reactions.

The affinity of Lucentis for VEGF is stronger than that of Avastin (although the company has declined to compare the efficacy of the two in clinical trials).

Because manufacturing standards for ophthalmic drugs are higher than cancer drugs, Avastin patients may be at risk for particulate matter.

Avastin and Lucentis are two different drugs designed to treat two different diseases, Ms. Kalmar says. For the company to backtrack and study Avastin as an ocular agent would be counterproductive, she says. We would have to go back and start where we were with Lucentis in 1999.

To date, no large-scale, randomized clinical studies of Avastin in eye disease have been conducted. However, it is uncertain whether all of Genentechs objections will hold up over time.

For example, the increased time in the eye due to Avastins longer half-life may prove to be an advantage. Though protocols for frequency of dosing are still being determined for both drugs, Avastin may require less frequent injections, perhaps because of its longer half life. Practitioners and patients see this as an advantage. Anecdotally, doctors report administering Avastin injections every three months, while data from the phase III clinical trials indicate that Lucentis may be most effective when dosed monthly.

Nor is the risk of inflammation settled. A recent study on Avastin patients found a curiously low rate of intraocular inflammation, when compared with that seen in Lucentis and Macugen, especially given that researchers were anticipating increased inflammation with Avastin.5 As a full-length antibody, Avastin was expected to cause increased inflammation because it contains an Fc portion. However, not all ligand bound to Fc receptors leads to immune system activation and actually can cause inhibitory effects, the study notes. Only further research could prove or disprove such a theory, the authors say.

There is also the matter of VEGF in general and its role in the eye. Although large multi-center trials with Macugen and Lucentis have raised no safety concerns, it is possible that too much inhibition of VEGF, a naturally occurring and often-beneficial growth factor, could prove detrimental in the long run. One paper cautions, There is speculation that blocking VEGF may cause an increased rate of apoptosis among ganglion cells and photoreceptors.9

Thus, Macugen is likely to play a continued role in the treatment of AMD and related disorderseither as an adjunct or prophylactic agent. Because Macugen targets only VEGF 165, pegaptanib may be safer for long-term use.

Macugen may be used in a kind of maintenance fashion, says optometrist Leo P. Semes, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The Avastin will put out the fire, and the Macugen will quell the embers."

The Future

While the advent of anti-VEGF treatments is cause for optimism, a large segment of patients fails to respond to these drugs. Avastin and Lucentis will probably prove to be better than current treatments, but they are still not perfect, Dr. Gerson says. I hope something better comes along at some point.

During the next few years, treatment may evolve into some kind of combination therapy, coupled perhaps with a prophylactic agent. The drug Retaane (anecortave acetate, Alcon) is undergoing study as a treatment for patients who have dry AMD deemed at risk for progressing to the wet form. Evizon (squalamine lactate, Genaera), another anti-angiogenic drug, also is in development.

If Avastin and Lucentis prove evenly matched in efficacy, and both retain their current safety profiles, financial considerations will likely have a larger impact on which prevails. In any event, the future of Genentech probably does not hang in the balance. In the wake of the Vioxx product liability lawsuits, biotech firms such as Genentech have replaced pharmaceutical companies as Wall Streets favored picks, and Genentech is the second largest in the world.

The lowered projected sales figures for Lucentis represented only a minor setback in what was a remarkably successful 2005 for the company. Financial experts predict Genentechs earnings will increase 43% this year.

Avastins off-label status will undoubtedly work against it, especially considering the unapproved method of drug delivery. Above all, though, anti-VEGF therapy has given retina subspecialists and their patients cause for enthusiasm. This is the first treatment where we are actually seeing improvement in visual acuity, as opposed to patients slowly getting worse, Dr. Dunbar says. That is the most important thing.

1. Moyer CA. Off-label use and the medical negligence standard under Minnesota law. William Mitchell Law Review, 2005 March;31(3):927-38.

2. Michels S, Rosenfeld PJ, Puliafito CA, et al. Systemic bevacizumab (Avastin) therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration twelve-week results of an uncontrolled open-label clinical study. Ophthalmology 2005 Jun;112(6):1035-47.

3. Rajpal S, Venook AP. Targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2006 Feb;4(2):124-32.

4. Rosenfeld PJ, Fung AE, Puliafito CA. Optical coherence tomography findings after an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) for macular edema from central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2005 July-Aug;36(4):336-9.

5. Spaide RF, Laud K, Fine HF, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab treatment of choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2006 Apr;26(4):383-90.

6. Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET Jr, et al. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 2004 Dec 30;351(27):2805-16.

7. Schachat AP. New treatments for age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2005 Apr;112(4):531-2.

8. Arons IJ. Avastin: A New Hope for Treating AMD Available at: http://irvaronsjournal.blogspot.com/2006/01/avastin-new-hope-for-treating-amd.html (Accessed October 2, 2006)