|

A 32-year-old male presented with sudden-onset blurry vision in his left eye after being punched about 12 hours earlier. He reported that, while walking to his car after leaving a restaurant, he was assaulted by an unknown man who punched him in the head and his eye. He reports “graying” of his central vision that extends inferior toward his nose. He also has a black eye and hemorrhaging on the outside of the eye. His past medical and ocular history is unremarkable.

On examination, visual acuities were 20/20 OD and 4’/200 OS, eccentrically viewing. Confrontation visual fields were full-to-careful finger counting in both eyes, but there was a central scotoma in the left. His pupils were equally round and reactive. We observed no afferent pupillary defect. Ocular motility was full. The anterior segment of the right eye was normal. The left eye showed significant periorbital swelling and ecchymosis. He had a subconjunctival hemorrhage in the left eye. The cornea was clear. The anterior chamber was 4+ deep and quiet. The iris and lens were normal. Tensions by applanation were 12mm Hg OU.

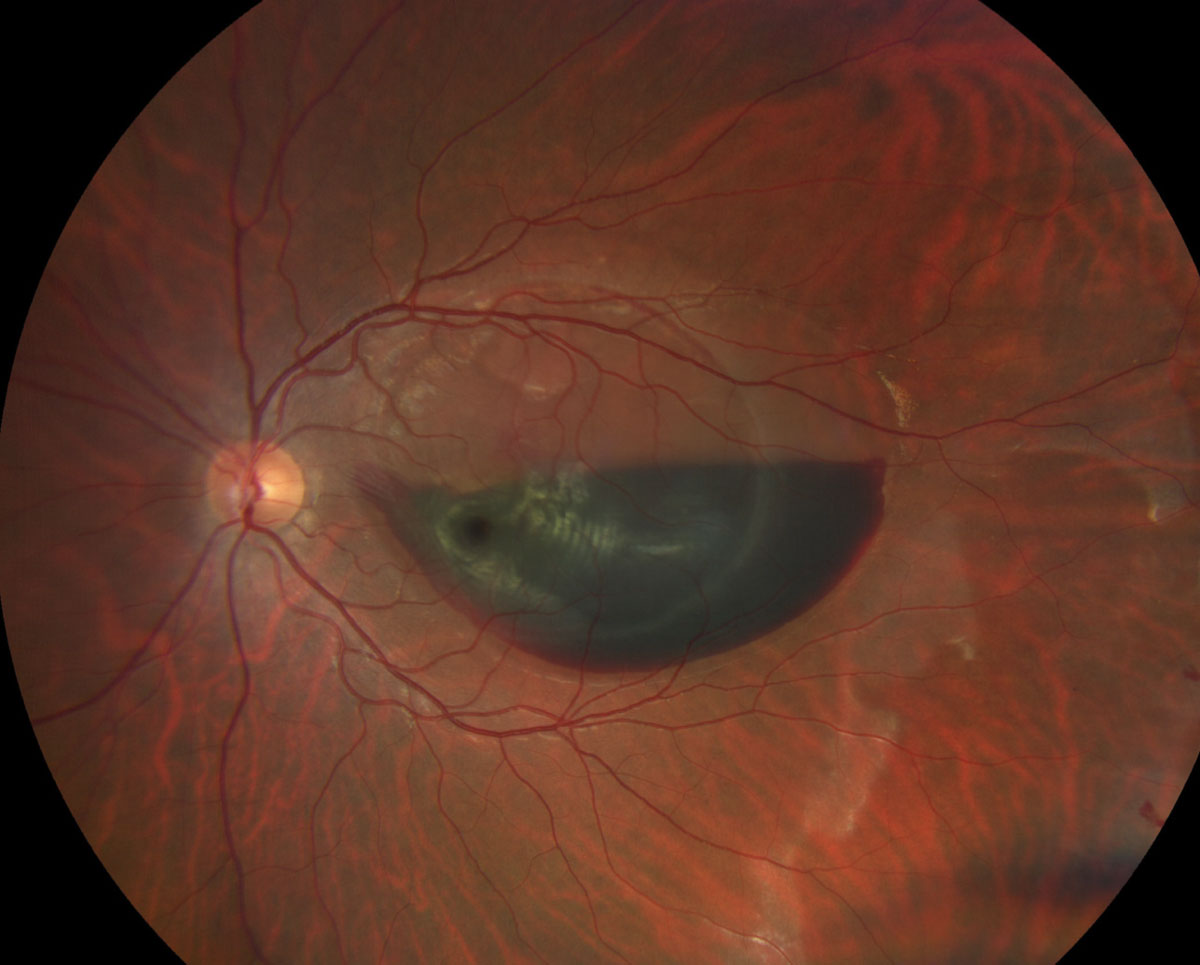

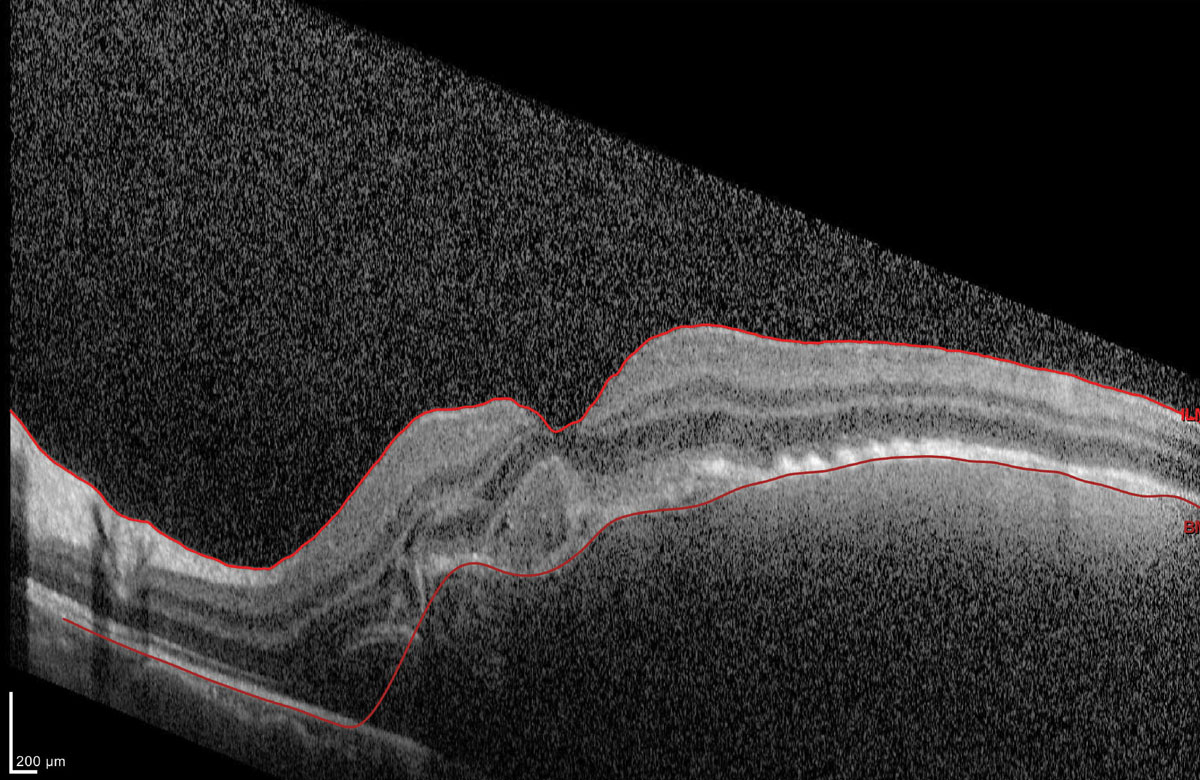

A dilated fundus exam of the right eye was normal, but left eye imaging revealed hemorrhage (Figure 1). An SD-OCT of the left eye is also available for review (Figure 2).

|

| Fig. 1. A view of the macula and posterior pole of the left eye of our patient. How would you characterize the hemorrhage? Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. How would you characterize the hemorrhage in the left eye?

a. Subhyaloid.

b. Preretinal.

c. Intraretinal.

d. Subretinal.

2. What is the likely etiology of the hemorrhage?

a. Hemorrhagic retinal detachment.

b. Retinal macroarterial aneurysm.

c. Choroidal rupture.

d. Valsalva retinopathy.

3. How should this patient be managed?

a. Careful observation.

b. Pars plana vitrectomy and evacuation of the hemorrhage.

c. PPV and scleral buckle.

d. Intravitreal anti-VEGF medication.

4. What is the prognosis for this eye?

a. Resolution and return to normal visual function.

b. Chorioretinal scarring and loss of central vision.

c. Possible development of choroidal neovascularization.

d. Too early to tell.

For answers, see below

|

| Fig. 2. What can this OCT image tell you about the patient’s macula? Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Our patient has a large subretinal hemorrhage that involves the macula. It is difficult to tell what else is going on because of all the hemorrhaging. The images clearly show elevation of the retina in the macula from the hemorrhage and possible subretinal fluid on the temporal side of the hemorrhage that extends superiorly. It appears there is a detachment of the posterior hyaloid of the vitreous surrounding the macula. We observed no retinal detachment.

An SD-OCT was performed and clearly shows elevation of the retina and significant subretinal hemorrhage. There was poor visualization of the posterior segment due to the dense hemorrhaging.

So, what is going on with our patient? The presence of the subretinal hemorrhage in the macula should be a clue. He likely developed a choroidal rupture as a result of the punch. The choroidal rupture develops from mechanical compression to the globe (from the blunt trauma), followed by sudden hyperextension of the globe. The sclera can often resist the mechanical forces that occur from blunt trauma, but the middle layers do not have the strength or the elasticity to resist these compressive forces. As a result, a rupture of the choroid, Bruch’s membrane and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) can occur. The presence of a subretinal hemorrhage in the setting of blunt trauma should arouse suspicion of a choroidal rupture. Commotio retina or Berlin’s edema, or both, can occur if the trauma is severe.

|

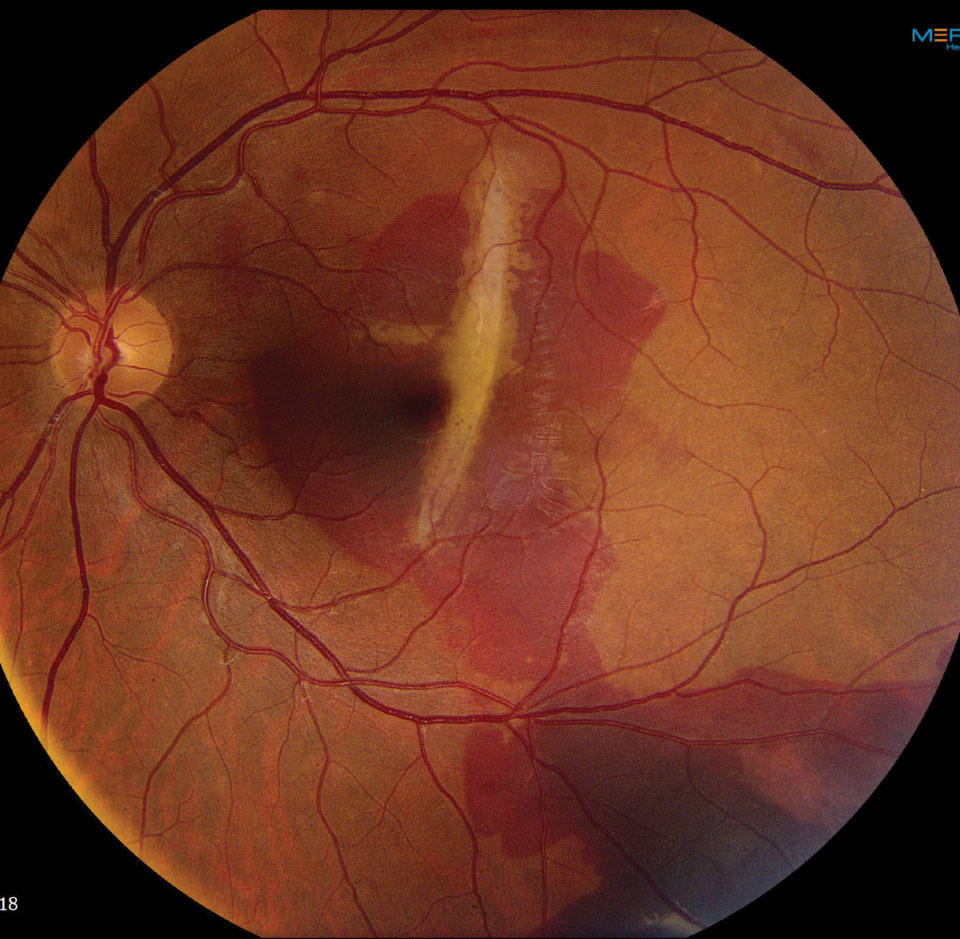

| Fig. 3. This fundus photo shows our patient two weeks later. What do you see now? Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Choroidal ruptures develop in approximately 5% to 10% of patients who present with blunt trauma.1 These lesions appear as radial cracks or defects in Bruch’s membrane and RPE and are often located temporal to the macula, but can develop anywhere in the posterior pole. They can be difficult to observe in the acute phase due to the subretinal hemorrhage and the acute nature of the event. But as the hemorrhage resolves, scarring and fibrosis will occur, making it easier to see.

Our patient was closely observed without treatment and the subretinal hemorrhage began to resolve. Indeed, within a few weeks, the characteristic white radial choroidal rupture was apparent but, unfortunately, it appeared to involve his central fixation (Figure 3). His acuity was 20/80 OS eccentrically viewing and there was a suspicion of an early choroidal neovascularization (CNV).

CNV is a common secondary complication of choroidal ruptures. New vessels can grow through cracks or defects within Bruch’s membrane. If left untreated, they will leak and bleed, resulting in further scarring. We plan to continue closely monitoring this patient, without any intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. If his condition worsens or the presence of a CNV is confirmed, intravitreal anti-VEGF injections will be the next step. n

Dr. Dillinger is a resident at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

| 1. Wyszynski RE, Grossniklaus HE, Frank KE. Indirect choroidal rupture secondary to blunt ocular trauma. A review of eight eyes. Retina 1988;8:237-43. |