Humbled by a ‘Good Catch’

Recently, I saw a new patient to our practice, a 61-year-old white female who worked as an accountant for the local school district. This was her first ever eye exam, and she’d been using cheaters since her mid-40s. She came in because her night distance vision seemed blurry for the past year, and thought it was time to take advantage of her vision plan.

Upon examination, her IOPs were normal and astigmatic refraction improved acuity from 20/50 to 20/20 OD and OS. Motilities and pupils were normal. Biomicroscopy was unremarkable. I instilled 1% tropicamide and had my staff perform our screening field while the patient dilated.

The fundus exam was normal, but the field results were a mess. My tech reported the patient’s fixation was all over the place, and since she was a hyperopic presbyope and it was her first field, my inclination was to set those results aside as spurious. While scrawling the glasses script, I commented on how special I felt getting to be her first eye doctor, especially at this point in her visual career. That’s when she admitted it was her husband who made her come in after she’d pulled out into oncoming traffic, and on another instance almost hit a pedestrian, both within the past month.

Those comments got my attention. I asked if both near misses were to the same side of her vision and, sure enough, both were in her right field. A quick confrontation field revealed a distinct bilateral homonymous hemianopsia respecting the midline.

Of course, it was 2 p.m. on a Friday. I immediately sent the patient to the ER with a handwritten note requesting intracranial imaging with my suspicion of a left side temporal or parietal lesion. I also described the nature of her field defect. I faxed a more detailed note to her PCP, which I understand he read the following Tuesday.

The patient’s oncologist called today and asked to speak with me personally. Unfortunately, he reported my patient’s grave diagnosis: multiform glioblastoma, the most aggressive of all brain cancers. Average mortality rate is three months after initial diagnosis, and often there is no treatment because the tumor has become so invasive. However, if caught early (we did), and with surgery (already done), followed by radiation and chemo (she’s doing both), recent studies at UCLA include cases with 10- and even 20-year life spans. Due to our early diagnosis and relatively smallish tumor size, the doctor has hopes our patient will be one of the latter cases.

The best part of this story? The oncologist finished our conversation with these two words: “Good catch.”

What does an OD say after that? Well, I would have said “thank you” if I hadn’t dropped the phone already.

—Jerome L. Brendel, OD, Yuba City, Calif.

Update from Dr. Brendel:

I called my patient to see how she was doing, and unfortunately she reported that her brain surgeon discovered during her craniotomy that her tumor was much larger than initial imaging projected. Therefore, he performed a partial resection and advised against chemo and radiation due to quality of life considerations.

Nevertheless, we had a very enjoyable conversation. She expressed gratitude for the opportunity to reconcile some fractured family relationships, and has been devoutly telling everyone she comes in contact with to “live for the day, because tomorrow is not a guarantee.”

As we said our goodbyes, she said, “Thank you, Dr. Brendel. You may not have saved my life, but you did help me experience more of the days I have left.”

For my part, I am humbled. And also thankful for the opportunity to practice optometry.

‘Myopia’ is Not ‘Nearsightedness’

Many of us use the terms myopia and nearsightedness interchangeably. We should stop.

Nearsightedness describes the subjective experience of blurred distance vision relative to near vision. Myopia is a condition that results in light being focused anterior to the macula often due to excessive axial length.

Semantics are an important aspect of language. If we choose language that more appropriately describes this condition and use the term myopia in the examination room when educating patients, it may lead to greater compliance with treatments that aim to limit myopia progression.

The fact that our society’s lexicon has equated nearsightedness with myopia has led to a ho-hum attitude towards this condition: “My child has a little blurred vision at distance and it has gotten worse over the past year, no big deal.”

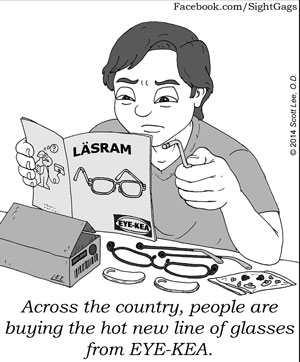

Sight Gags by Scott Lee, OD |

But it is a big deal. The prevalence of myopia is increasing worldwide and the implications of myopia are well known and include increased risk of maculopathy, retinal detachment, glaucoma and earlier cataracts. How the increased rates and severity of myopia in today’s youth will impact ocular health data in 40 years remains to be seen, but many believe we should attempt to limit myopia progression because of the compelling evidence mentioned.

The difference between myopia and nearsightedness not only affects patient education and treatment decisions but also impacts research. Over the years, there have been many attempts at limiting myopia progression—including corneal reshaping/orthokeratology, atropine ophthalmic drops, soft bifocal contact lenses, bifocal glasses, progressive addition lenses, vision therapy and more. Vision therapy—while extremely effective for many binocular vision, accommodative, oculomotor and visual perception deficits—has no research supporting its effectiveness in myopia control. Any publication supporting vision therapy has described improving nearsightedness through improved blur interpretation with less myopic lens compensation. Vision therapy may be able to limit the progression of myopia but it hasn’t been proven yet. Any research that is purported to improve myopia should include axial length measurements over time and cycloplegic refractive status.

There has been quite a bit of buzz over myopia these last few years. I hope you join me in cleaning up the language we use to help increase awareness of this important public health issue.

—Daniel J. Press, OD, Clinical Director of Pediatrics, Binocular Vision and Vision Therapy, North Suburban Vision Consultants, Park Ridge, Ill.

Signs of Traumatic Cataract

I am writing in regards to “Caution! Traumatic Cataracts Ahead” in the April 2015 issue. The authors did a very nice job of describing the challenges of surgery on traumatic cataracts. It would have been even better had they described the clinical signs that might suggest a traumatic cataract is present. It is the role of the OD to detect and inform the surgeon of these clinical signs.

Patient history is the first line of defense in detecting traumatic cataract and potential negative sequelae. Even if the patient has denied trauma earlier in the exam, it is a good idea to ask again. Sometimes patients forget trauma that was years or decades in the past and then later remember the event, but they may not bring it up unless you ask about it another time.

Clinical clues to significant ocular trauma include any full-thickness corneal scar, a dyscoric pupil, iridodialysis, iridodonesis (a fluttering motion of the iris on ocular movement) and iridocorneal adhesion in conjunction with a full-thickness corneal scar. Gonioscopy should be performed looking for angle recession.

On dilated exam, the lens should be evaluated for phacodonesis (a fluttering of the lens on eye movement), subluxation, peripheral blunting of the lens margins (indicating zonular dehiscence) and for the integrity of the capsule. Any presence of vitreous in the posterior or anterior chamber is also evidence of zonular compromise.

Fundus exam, if possible, should include a careful check for peripheral retinal tears or dialysis and lacquer cracks in the macula or around the disc.

If significant zonular dehiscence and subluxation is present, it may be best to have the cataract removed via a pars plana approach by a retinal subspecialist (so that vitreous can be controlled and any retinal issues addressed) with a subsequent surgery for IOL implantation, either with an anterior chamber IOL or a posterior chamber IOL with iris sutures. This should be discussed with the selected surgeon(s).

Thanks for your great work in educating our profession.

—Howell M. Findley, OD, Lexington, Ky.