As optometrists, we are acutely familiar with and regularly encounter ocular emergencies, be it chemical burns, macula-on retinal detachments or acute angle-closure glaucoma. We are also prepared for conditions with ocular manifestations, such as pupil-involving third nerve palsy, papilledema or central retinal artery occlusions. However, we may be less prepared for systemic emergencies that can arise in the office.

Studies suggest that non-hospital medical offices are often ill-equipped and unprepared for medical emergencies due to rarity, time and financial constraints for training.1,2 In addition, some offices may not invest in emergency preparedness because of the perceived proximity to hospitals for easy transfer.1,2 While medical emergencies in the office may be uncommon, proper management is critical to avoid serious complications when they do happen.

This article reviews common medical emergencies you may encounter in the office and how quick thinking and an appropriate response can play a critical role in achieving positive outcomes for your patients.

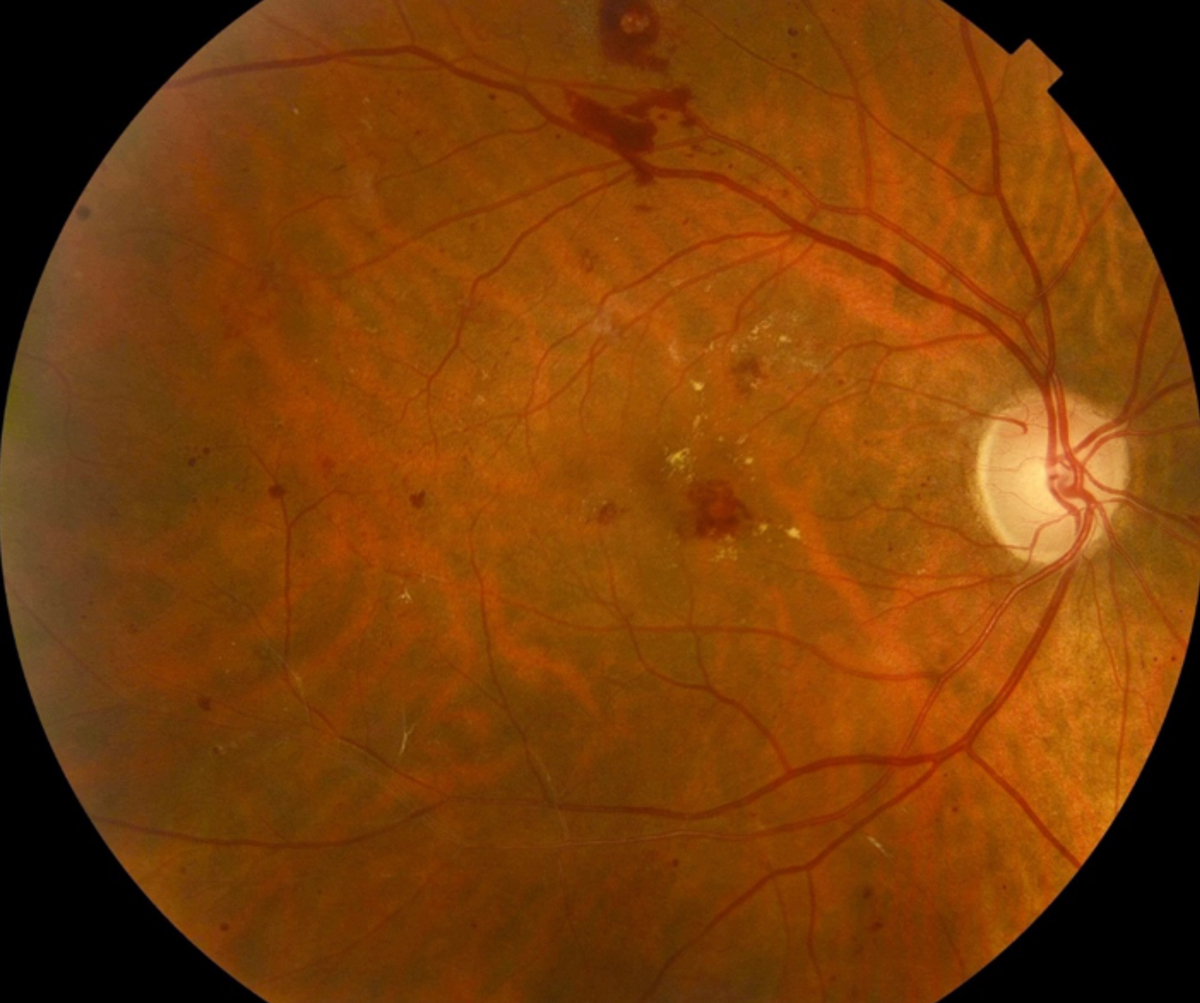

|

| Diabetic patients, such as this one with moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, are commonplace in the optometry practice, and are more prone to hypoglycemic symptoms, especially those who need insulin to control their blood glucose. Click image to enlarge. |

Initial Assessment

Patient emergencies are stressful situations, and it may be difficult to think and react clearly. To make the initial assessment easier, start with the “ABCDE” approach: Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability and Exposure:2-4

- Airway: assess the patient’s breath sounds for any strain and check the patient’s voice (normal voice means a patent passageway). Stabilize this passageway with a head tilt and chin lift.

- Breathing: check respiratory rate, chest wall movements and pulse oximetry, if possible. Seat the patient comfortably (or have them lie down, if needed) and provide rescue breaths or further ventilation, if needed.

- Circulation: evaluate skin color, sweating, capillary refill time (ideally below two seconds) and blood pressure. Stem any bleeding, if present, and elevate the legs to return blood flow to the head, if necessary.

- Disability: evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness—is the patient alert, voice responsive, pain responsive (i.e., via sternal rub with knuckles) or unresponsive—and limb movements and pupillary reflex.

- Exposure: keeping patient privacy and dignity in mind, expose skin to evaluate for any clues to cause of patient’s emergency episode.

This systemic approach is applicable in all clinical emergencies (aside from cardiac arrest, see below), is applicable for children and adults alike and is used by those who deal with clinical emergencies often, including EMTs, critical care specialists and trauma specialists. This technique provides a good starting point in the proper care for the patient. Further intervention is case dependent. Here is how to manage symptoms that may be more commonly seen in optometry offices:

Fainting

Syncope is defined as a transient, sudden and temporary loss of consciousness with spontaneous and relatively prompt recovery.5,6 The most common form of syncope optometrists are likely to encounter is vasovagal syncope (i.e., fainting), which can be triggered by an number of common ocular examination components including tonometry, gonioscopy, punctal plug insertion, contact lens insertion and eyedrop instillation.

This reflex is complex, involving emotional or orthostatic stress that stimulates the vagal neurons in the central nervous system, causing a decrease in sympathetic output (and concurrent increase in parasympathetic output) to the heart and vasculature of the body. This process results in marked vasodilation, bradycardia and hypotension.5,7 Ultimately, this combination may lead to inadequate cerebral perfusion, triggering a loss of consciousness.6 Patients undergoing an episode may exhibit sweating, pallor and hyperventilation and may note symptoms of fatigue, dizziness, blurred vision, loss of hearing and nausea.5,7

Recognizing a possible oncoming episode of vasovagal syncope is key, as loss of consciousness may be avoided with early intervention by having the patient sit or lie down if they start noting the above symptoms.7 Blood flow should be directed towards the head by elevating the patient’s legs (the Trendelenburg position), if possible, to help return blood flow to the head, and you should follow the standard ABCDE evaluation.

The patient should return to consciousness in a short period of time, and while they may be weak, it is rare for the patient to exhibit severe confusion.7 Once the patient has regained consciousness, allow them to remain supine and relaxed, during which time you should reassure and monitor them with periodic checking of blood pressure and pulse strength and rate.

It is prudent to document the episode and note it for future visits, especially if it helps you avoid potential triggers. A single episode of vasovagal syncope with a known trigger usually does not warrant medical workup; however, you should evaluate repeat episodes or unknown cause of a syncope episode to rule out other underlying systemic disorders.5,7

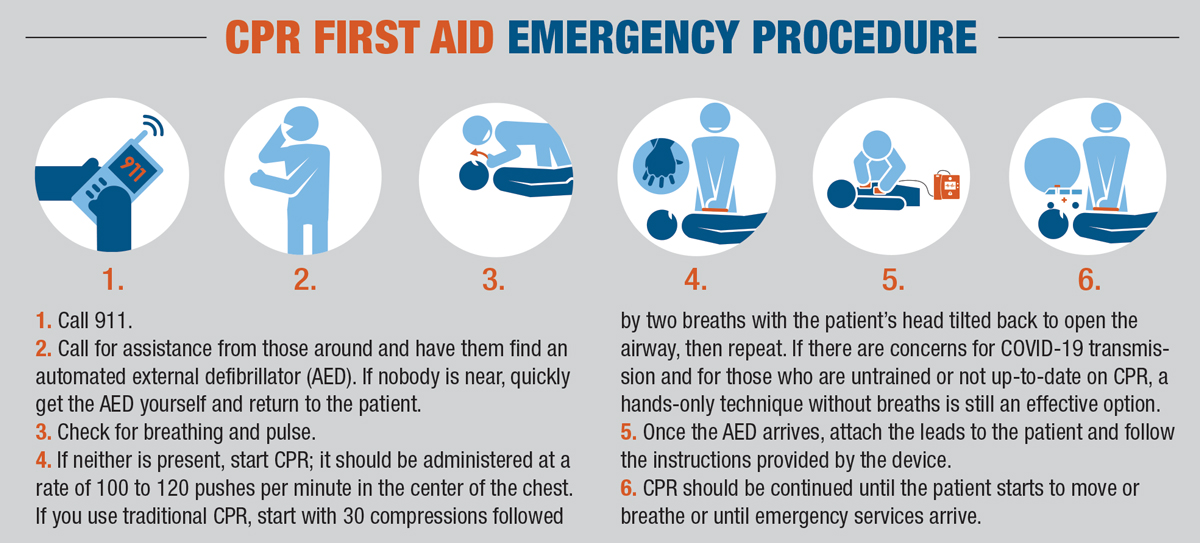

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Anaphylaxis

This is a serious systemic hypersensitivity reaction that can be life-threatening. Incidence of anaphylaxis is on the rise, particularly due to food allergies in younger patients; insect stings and medication responses continue to be more prevalent in adult patients.8,9

This allergic response is driven by IgE antibodies that form after initial exposure to an antigen and bind to mast cells and basophils; subsequent exposure leads to crosslinking of the bound IgE and release of mediators such as histamine.10

Patients exhibiting anaphylaxis may present with a sudden onset of a variety of signs and symptoms, including hives, itching, swollen lips/tongue/uvula, shortness of breath, wheezing, reduced blood pressure (age-dependent for children, <90mm Hg systolic for adults), gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and acute coronary syndrome.9,10

According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, to diagnose anaphylaxis or the suspicion of it, the patient should meet one of these three clinical criteria:11

- Acute onset (minutes to hours) of an illness with involvement of the skin, mucosal tissue or both and at least one:

- Respiratory compromise

- Reduced blood pressure or associated symptoms of end-organ failure

- Two or more of the following that occur rapidly after exposure to a likely allergen:

- Involvement of skin and mucosal tissue

- Respiratory compromise

- Reduced blood pressure or associated symptoms

- Persistent gastrointestinal symptoms

- Reduced blood pressure after exposure to a known allergen

While a major finding in most cases of anaphylaxis, skin symptoms such as hives may be absent in around 10% of cases and may be delayed in their onset when they do occur, so you should not rely on them as the only determinant when considering anaphylaxis.8

After calling for emergency medical services, the essential first-line treatment for an anaphylactic episode is an intramuscular injection of epinephrine into the mid outer thigh, which may be given through clothing if needed.8,9,12,13 Dosage is dependent on size and age: adults should receive a maximum of 0.5mg, and children should receive a maximum of 0.3mg.9 This may be delivered via a needle and syringe or an autoinjector such as an EpiPen (epinephrine injection, Mylan) or Auvi-Q (epinephrine injection, Kaléo).

Epinephrine acts quickly through alpha and beta sympathomimetic actions to cause vasoconstriction, increased cardiac output, bronchodilation and inhibition of further inflammatory mediators from mast cells and basophils.8,9 Second-line agents such as steroids, histamine-1 antagonists or beta-2 adrenergic agonists may be helpful in more chronic situations but are not an acceptable substitute for epinephrine during an acute attack.9,12

Patients experiencing an anaphylactic episode should be laid in the Trendelenburg position to maximize blood flow to the head while blood pressure, heart rate and respiratory status are monitored.9 Patients may need a second injection if they do not respond to the initial dose. All patients should be seen by emergency services after injection, regardless of response, for further monitoring.

Anaphylaxis can occur with any medication, and you should prepare your staff to respond when necessary. Some states allow optometrists to perform fluorescein angiography, which has been known to cause rash/urticaria, laryngeal edema or bronchospasm, cardiovascular events and even death.14,15 Reports also highlight the potential for anaphylactic reactions to topical eye drop use.16,17 While the occurrence of an anaphylactic episode in office is rare, it is important to know the signs and symptoms and initiate prompt treatment.

Hypoglycemia

This is the most common and most serious side effect of treatment to lower blood glucose in diabetic patients.18 Aggressive treatment to decrease hemoglobin A1c may lead to higher risk of hypoglycemic episodes, and this risk is particularly high in patients who are on insulin to control their blood glucose.18 Symptoms of hypoglycemia present as autonomic changes—trembling, sweating, anxiety, hunger, nausea or tingling—and neuroglycopenic changes such as confusion, difficulty concentrating, drowsiness, vision changes, dizziness and headache.18,19

Any number of these signs are caused, most commonly, by insufficient consumption of food, although it may occur due to physical exercise, stress, miscalculation of insulin dose or oscillating blood sugar levels.18 Hypoglycemia is defined in stages:19

Mild hypoglycemia (blood sugar between 56 and 70mg/dL): autonomic symptoms present, patient may be aware and self-treat

Moderate hypoglycemia (blood sugar between 40 and 55mg/dL): autonomic and neuroglycopenic symptoms both present, patient may be aware and self-treat

Severe hypoglycemia (blood sugar <40mg/dL): more severe symptoms, patient needs assistance with treatment and may become unconscious with potential for coma or seizure

As we encounter diabetic patients in increasing levels in practice, it is important to recognize these manifestations of hypoglycemia and treat them before potentially serious or fatal complications occur.

For patients who are conscious, the American Diabetes Association recommends the “15-15” rule—ingest 15g of a simple carbohydrate, such as glucose tablets, four ounces (1/2 cup) of juice or regular soda, one tablespoon of sugar or honey or hard candies (amount varies by what is being eaten), and check blood sugar after 15 minutes; if blood sugar remains below 70mg/dL, provide the patient another serving.20 This should be adjusted for young children, who usually need less than 15g to return to normal blood sugar readings.20 Patients in severe hypoglycemia may require more initial carbohydrate consumption (20g) to get a more robust initial spike in blood sugar.19

Those who are unconscious require urgent care, and emergency response should be contacted immediately. In these cases, it is important to avoid injection of insulin, as it would further reduce blood sugar levels, or to attempt to provide food, drink or other oral therapies, as these are choking hazards. These patients may have glucagon injections that can be administered by a family member intramuscularly or subcutaneously.19 More recently, glucagon has been formulated as an intranasal spray, which may be easier to administer to patients in need.21 Patients who are administered glucagon may regain consciousness with resulting nausea or vomiting.20

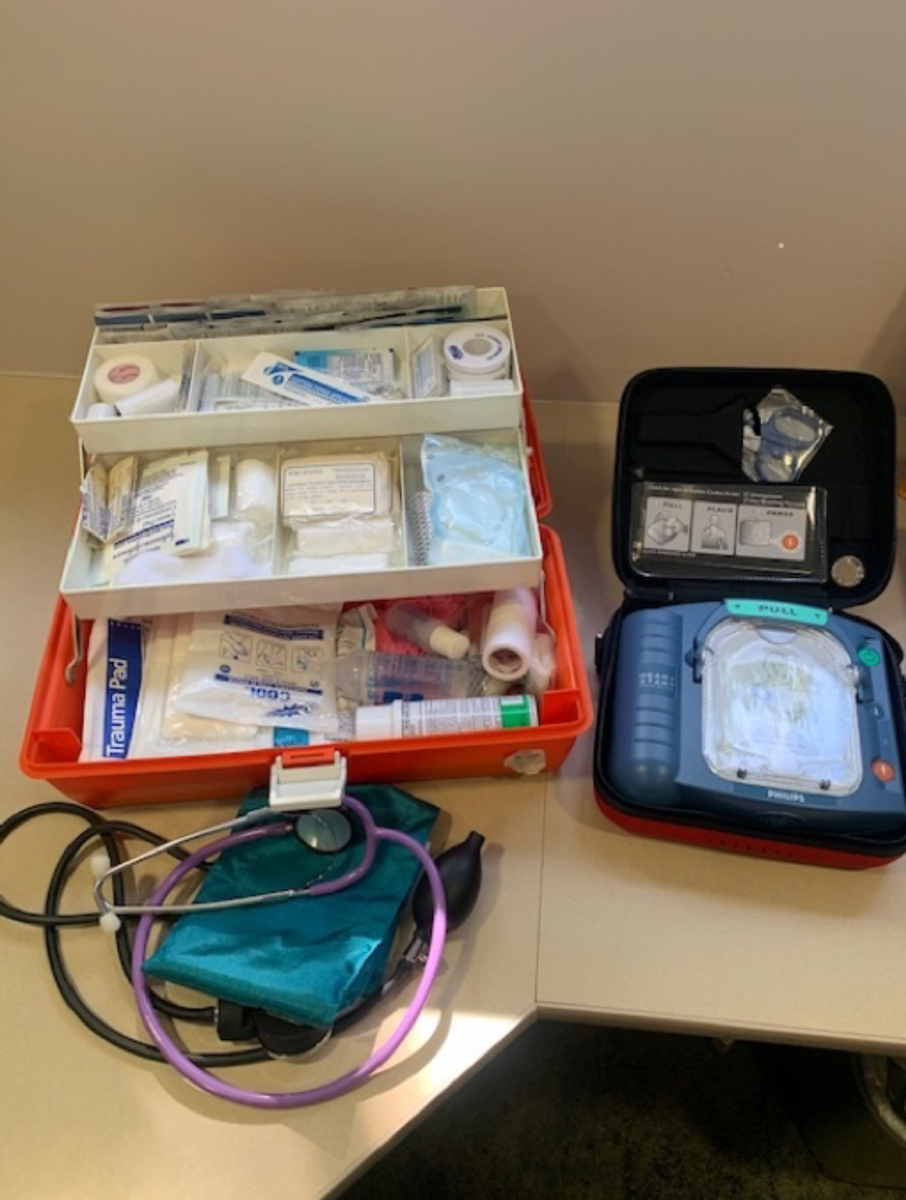

|

An office emergency preparedness kit may include items such as blood pressure cuffs, first aid kit and an AED. Place these items in a well-marked location that is easy to access. Click image to enlarge. |

Heart Attack and Cardiac Arrest

Heart disease is among the leading causes of death in the United States.22 Among the potential manifestations of heart disease is acute myocardial infarction, or heart attack, which is caused by a decrease or stoppage of blood flow to part of the heart, leading to necrosis of the heart muscle, most commonly due to atherosclerosis.23 Patients with hypertension, high cholesterol and those who smoke are at higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease that may result in heart attack.22

Symptoms of heart attack include chest pain or discomfort, jaw or neck pain, arm or shoulder pain and shortness of breath.24 Women may also have more atypical symptoms including nausea, vomiting, unexplained fatigue and pressure in the lower chest and upper abdomen.25

One of the most important steps in managing heart attack is getting these patients to a hospital for emergency cardiac care.26 For patients who are symptomatic for heart attack, call 911 immediately. Give the patient a dose of 325mg aspirin (without enteric coating) to chew for faster systemic absorption and provide water for them to swallow.25,26 Monitor the patient until EMTs arrive for transfer to an emergency room with cardiac care.

Roughly one in 20 cases of heart attack may lead to sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), where the heart ceases beating altogether.27 The progression to SCA is perhaps the most devastating outcome of heart attack, as studies show a mortality rate of 37.7% compared with 4% of heart attack patients who do not progress to SCA.

You should bypass the ABCDE assessment for patients experiencing SCA.3 If you encounter an unresponsive patient, the American Heart Association recommends beginning the administration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (see, “CPR First Aid Emergency Procedure”):28

With any concern for heart attack, and especially in cardiac arrest, prompt emergency response is vital.29 Perhaps the next most important step towards patient survival is the use of an automated external defibrillator (AED). A recent study shows that bystander use of AED for SCA provides a significant increase in survival rate (66.5% vs. 43.0%) and favorable outcome after hospital discharge (57.1% vs. 32.7%) compared with SCA patients who were first given cardioversion by emergency medical services.30

All AEDs provide step-by-step instructions in its use, and come equipped with the tools necessary to monitor for pulse and deliver electric shock, when needed.

If your office has access to this device, ensure that all doctors and staff know where it is so they can quickly retrieve it in an emergency. Some offices may not be equipped with an AED due to the high cost and rarity of in-office SCA. In this case, you can consult with other medical practices or businesses nearby to see if they have a device that you can access in the event of an emergency.

Preparation is Key

These emergencies are, fortunately, a rare occurrence in an optometrist’s day-to-day practice, but being ready to react when they do happen is critical. Regular refreshers on both CPR and Basic Life Support training will provide you and your staff any new recommendations. Many states require optometrists to be current with these certifications.

You should also have plans in place that prepare staff to jump into quick action when these events occur. Keep emergency items such as a first aid kit, blood pressure cuff, pulse oximeter and an AED in a well-marked place and ensure that all staff know where to access this equipment. Keeping sugary drinks or foods in the office to provide to diabetes patients entering a hypoglycemic episode is prudent.

A set preparedness plan will help guide your team in the case of emergency. Many versions exist through multiple regulatory bodies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.31 Regular review of these plans with your staff may be helpful.

However rare these emergencies may be in clinical practice, is important that we remain prepared for whatever walks through the door. Prompt and proper management may play a vital role in achieving a positive outcome for your patient.

Dr. Kruthoff is an optometrist at Northwest Eye Clinic in Golden Valley, MN. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry.

1. Toback SL. Medical emergency preparedness in office practice. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(11):1679-84. 2. Wheeler DS, Kiefer ML, Poss WB. Pediatric emergency preparedness in the office. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(11):3333-42. 3. Thim T, Krarup NHV, Grove EL, et al. Initial assessment and treatment with the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:117-21. 4. Rothkopf L, Wirshup MB. A practical guide to emergency preparedness for office-based family physicians. Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(2):13-18. 5. Aydin MA, Salukhe TV, Wilke I, Willems S. Management and therapy of vasovagal syncope: A review. World J Cardiol. 2010;2(10):308-15. 6. Sutton R. Reflex syncope: Diagnosis and treatment. J Arrhythmia. 2017;33(6):545-552. 7. Fenton AM, Hammill SC, Rea RF, et al. Vasovagal syncope. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(9):714-25. 8. Anagnostou K, Turner PJ. Myths, facts and controversies in the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(1):83-90. 9. Simons FER, Ardusso LRF, Bilò MB, et al. World Allergy Organization guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J. 2011;4(2):13-37. 10. Reber LL, Hernandez JD, Galli SJ. The pathophysiology of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immu-nol. 2017;140(2):335-48. 11. Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):391-97. 12. Ring J, Grosber M, Möhrenschlager M, Brockow K. Anaphylaxis: acute treatment and man-agement. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2010;95:201-10. 13. Simons FER, Ardusso LR, Bilò MB, et al. International consensus on (ICON) anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7(1):9. 14. Ha SO, Kim DY, Sohn CH, Lim KS. Anaphylaxis caused by intravenous fluorescein: clinical characteristics and review of literature. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9(3):325-30. 15. Anaphylactoid reactions to fluorescein. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101(6):S519-S520. 16. Shahid H, Salmon JF. Anaphylactic response to topical fluorescein 2% eye drops: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:27. 17. Anderson D, Faltay B, Haller NA. Anaphylaxis with use of eye-drops containing benzalkonium chloride preservative. Clin Exp Optom. 2009;92(5):444-46. 18. Kalra S, Mukherjee JJ, Venkataraman S, et al. Hypoglycemia: The neglected complication. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(5):819-34. 19. Clayton D, Woo V, Yale J-F. Hypoglycemia. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37:S69-S71. 20. Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Glucose). American Diabetes Association. www.diabetes.org/diabetes/medication-management/blood-glucose-testing-and-control/hypoglycemia. Accessed June 15, 2020. 21. Yale J-F, Dulude H, Egeth M, et al. Faster use and fewer failures with needle-free nasal glucagon versus injectable glucagon in severe hypoglycemia rescue: a simulation study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2017;19(7):423-32. 22. Fryar CD, Chen TC, Li X. Prevalence of uncontrolled risk factors for cardiovascular disease: United States, 1999-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(103):1-8. 23. Saleh M, Ambrose JA. Understanding myocardial infarction. F1000Research. 2018;7. 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart attack symptoms, risk factors, and recovery. www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/heart_attack.htm. Published May 19, 2020. Accessed June 15, 2020. 25. Zagaria, MAE. Myocardial infarction in women: milder symptoms, aspirin, and angioplasty. US Pharma. 2017;42(2):5-7. 26. Reddy K, Khaliq A, Henning RJ. Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of acute myocardial infarction. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(5):243-76. 27. Karam N, Bataille S, Marijon E, et al. Incidence, mortality, and outcome-predictors of sud-den cardiac arrest complicating myocardial infarction prior to hospital admission. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(1):e007081. 28. American Heart Association. Emergency treatment of cardiac arrest. www.heart.org/en/health-topics/cardiac-arrest/emergency-treatment-of-cardiac-arrest. Accessed June 15, 2020. 29. Andersson PO, Lawesson SS, Karlsson J-E, et al, on behalf of the SymTime Study Group. Characteristics of patients with acute myocardial infarction contacting primary healthcare before hospitalisation: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):167. 30. Pollack RA, Brown SP, Rea T, et al. Impact of bystander automated external defibrillator use on survival and functional outcomes in shockable observed public cardiac arrests. Circulation. 2018;137(20):2104-13. 31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medical office preparedness planner. www.cdc.gov/cpr/readiness/healthcare/documents/Medical__Office_Preparedness_Planner.PDF. Accessed June 15, 2020. |